-

Posts

619 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

News

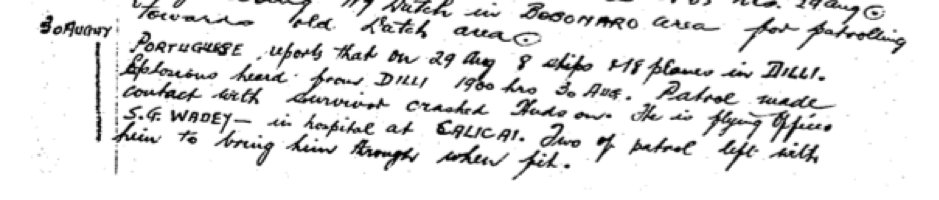

Video & Audio

Men of the 2/2

Forums

Store

Gallery

Posts posted by Edward Willis

-

-

With Christmas rapidly approaching those of us living in WA and old enough will fondly recall the Christmas Parties the old Association held for the children of members between 1952 and 1963.

Col Doig recounted the history of the Christmas Parties in Chapter 4 his book ‘A Great Fraternity: the story of the 2/2 Commando Association, 1946-1992’. Col’s account is redolent of earlier, simpler times with free kegs of ginger beer sourced from the Swan Brewery and tubs of ice cream from Peters, while the bonds of friendship that impelled the men and their wives to organise and conduct these parties shines through.

Col Doig’s ‘President’s Christmas Message’ and an account of the ‘Christmas Party’ are shown in the attached images from the December 1954 ‘Courier’.

BEST WISHES TO ALL MEMBERS AND SUPPORTERS FOR CHRISTMAS AND THE NEW YEAR!!

CHAPTER 4

CHILDRENS PARTIES & OUTINGS

When the Association was formed only a few of our Members were married so we had to wait quite a few years for the 'Stork Stakes' to provide enough offspring to indulge in children’s’ parties but, of course, the inevitable had to happen sooner or later.

The huge task of collating the names, sex and ages of the children took up considerable space in many Couriers. Having decided on a Christmas Party, the matter of appropriate presents had to be looked into, as well as catering, cool drinks, ice cream etc. Also, it was necessary to have a good venue and adequate entertainment. Many were the meetings until everything fell into some sort of order.

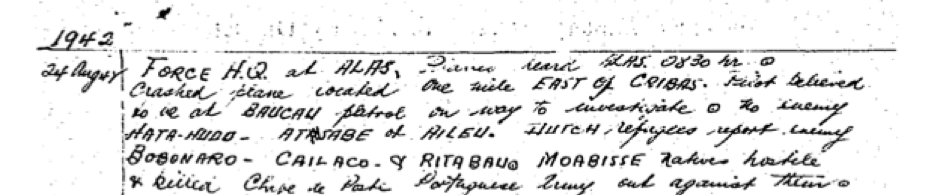

There were special working bees to packet lollies, wrap and label the parcels for the children. What order out of chaos used to occur at Col Doig's office. Sticky fingers from lollies, cut fingers from string and all the foibles that such preparations could bring. In those days it was possible to get kegs of free ginger beer from the Swan Brewery. Someone would scrounge cheap cool drinks and we would try Peters for at least one free churn of ice cream, and the hall had to be decorated. We had some sort of priority with the 16th Battalion Drill Hall through Tom Nisbet who was the then C.O. of the 16th Bn. (Cameron Highlanders).

The first of these great days was held in December 1952 and what a day of bedlam! We engaged Frank Fenn to act as clown and handle, proceedings. We had Alvero the Magician pulling white rabbits, pigeons and guinea pigs out of the hat and allowing the kids to cuddle them. He also ran a good Punch & Judy show. Clem Booth, a mate of Jack Carey, showed some good cartoons. Ken (Curly) Bowden made an enormous top hat which was strategically placed over a tunnel and the presents were pulled from this by our clown. The sweat and tears of the poor buggers in the tunnel handing out the presents had to be endured to be understood. It was a marvellous day, enjoyed by everyone except a few harassed mums. There were over 100 children present and gifts were sent to the known children who did not attend, especially those in the country. The usual small raffle was conducted to defray expenses.

As a result of this successful function a lot more names of children started to come forward so, by the time the second party was held in December 1953, numbers had increased quite considerably. The same panic in the purchase of presents occurred and the working bees and the hassles were probably even greater. In a moment of aberration Frank Freestone offered to make toffee apples and either Bernie Langridge or Bill Rowan-Robinson supplied the apples - that was the easy part!

Nobody was game to speak to Frank, going by the look on his face. According to 'Murphy's Law' everything that could go wrong did go wrong. The toffee got all over their kitten and stuck to everything but the apples and had to be boiled again.

Frank had a big laugh about it all a few days later but didn't see anything funny on that Sunday. We still had Frank Fenn and the magician to provide fun and the cartoons had the kids enthralled. The number had grown to 120 in 1953 and we forwarded heaps of presents to the country.

This pattern continued until 1959. As the children grew older the purchase of appropriate gifts became more difficult and eventually it was decided that books were a better proposition.

At one function a 'horse suit' was hired and George Strickland and Spriggy McDonald provided the front and rear portions of the steed. The kids had great fun - afraid the same couldn't be said for the innards of the horse.

Curly Bowden manufactured a reasonable sleigh in which Father Christmas was pulled around the hall by some stalwart adults and heaps of kids. As Fred Napier or Arthur Smith donned the suit it was quite a weight to handle.

A lot of people worked really hard for these functions. In 1957 Gerry & Lal Green worked like tigers to get the show going and Spriggy McDonald, Curly Bowden, Bill Epps, Mick Calcutt to name but a few, gave of their time and abilities to make these shows a success. We were lucky to have the services of Frank Fenn who was a minor genius at keeping children amused.

In 1959 an innovation was a fairy floss machine which was really appreciated by the children. The blokes operating the machine didn't have it all that easy, as the sticky, sugary substance clung to their aprons.

Because the children were growing up it was decided that the Zoo would be the best venue for future shows. This was commenced in 1960 and proved to be an immense success. A good roll up, plenty of fun with rides on the train, thanks to Harold Brooker who controlled this function as well as looking after the elephants. Races of all natures and the fairy floss managed to keep everyone happy and the wide open spaces of the Zoo gave plenty of scope for exuberance. Frank Fenn was still Master of Ceremonies. This venue was used until 1963, when functions ceased as the children were really growing up.

In the period 1952-1963, many children, and adults, had a good day out. During this time there was no grog available as it was felt that, for one day of the year we should not indulge and get off centre with the ladies and children. [1]

[1] Col Doig. - A Great Fraternity: the story of the 2/2 Commando Association, 1946-1992. – Perth: C.D. Doig, 1993: 23-26. The book is unfortunately out of print.

-

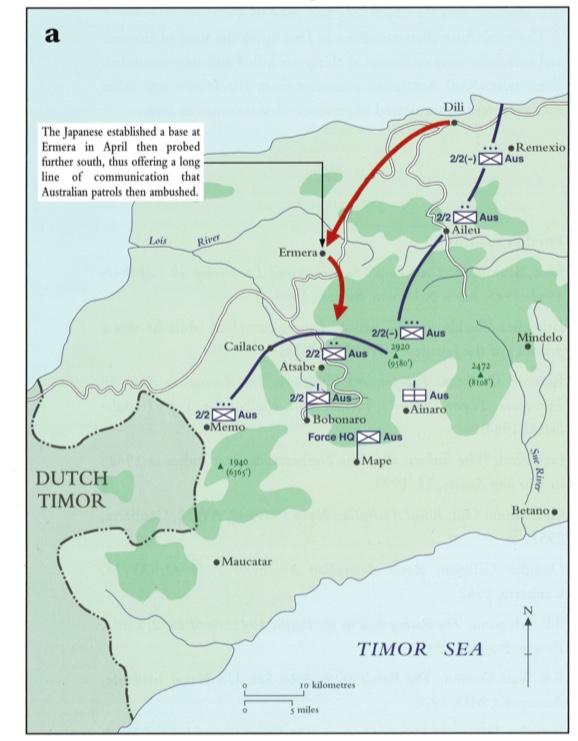

COMMANDO CAMPAIGN SITES – EAST TIMOR

DILI

DILI HELIPORT – JAPANESE BUILT WWII AIRFIELD EXTENSION

LOCATION

Coordinates: 8°33'22"S 125°33'45"E

The Dili Heliport occupies the site of an airfield built by the Japanese occupation force between March-July 1942. It lies just south of the Av. Pres. Nicolau Lobato, Dili, bounded on the eastern side by the Presidential Palace and on the western side by the Ministry of Defence. The Australian Embassy and Sparrow Force House reside on the opposite side of the Av. Pres. Nicolau Lobato to the north.

Map showing the location of the Dili Heliport

Though never carried forward, at various times during late 1942 and early 1943 consideration was given to re-taking Timor. Horner states that ‘In December [1942] the Advisory War Council had instructed the Chiefs of Staff to prepare to capture the island. The Chiefs had refrained, claiming that they had insufficient information’. [1]

This was the context in which the 'Area Study of Portuguese Timor' [ASPT] was prepared by former No. 2 Independent Company Section Commander, Captain David Dexter. The ‘Terrain study’, as it is subtitled, was released on 27 February 1943 and provides the following detailed description of the airfield in Dili that was such a critical focus of the Commando Campaign. It will be noticed in the text that particular attention is given to landing places and how to approach it in order to mount an effective attack. [2]

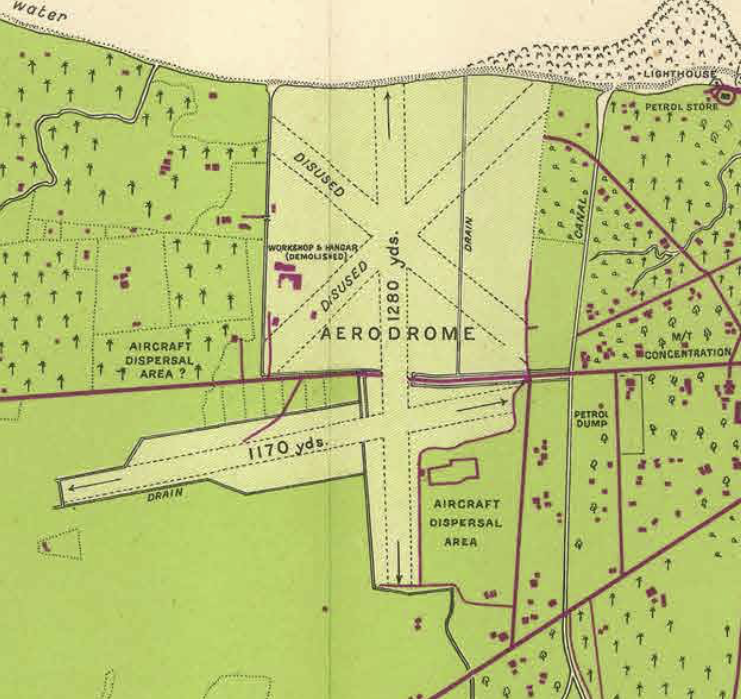

3. Airdromes:

This airdrome is located on a level stretch of land on the north coast of Portuguese Timor, 11/2 miles (2 km.) west of the town of Dilli, and now consists of two prepared strips, one N/S [North/South], 1,290 yards (1,180 m.) and the other E/W [East/West], 1,250 yards (1,140 m.). This latter runway and the southern portion of the former are situated on ground to the south of the main coast road which formed the south boundary of the old Portuguese airdrome area and constitute an extension by the enemy. Further extension of the N/S runway to the South appears possible.

Dili ‘aerodrome’ plan (1943) from ASPT map of Dili, Portuguese Timor [3]

It may also be possible to extend the E/W runway to the East by removing trees and houses. Extension to the West appears impracticable, as this would run out into the paddy fields, which are periodically flooded by the Comoro River. Coral and limestone surfacing material are available and have been used for repairing the runways.

The airdrome is between one and two miles (11/2 km. and 3 km.) to the north of the foothills of a mountain range which rises to 6,000 feet (1,840 m.) approx. 5 miles (8 km.) from the site. There is open sea to the North and northeast. On all other sides the only obstructions are trees and native houses near the boundaries of the landing area. The topography of the foothills is such that a rather sharp turn is necessary in approaching from the southeast.

In the wet season, December to March, clouds with a base of 1,000 feet are common on the foothills of the mountain range.

Dispersal facilities are limited. The enemy appears to make use of a clump of trees along the eastern edge of the N/S runway and just south of the E/W runway and in the coconut plantations to the west of the old airdrome area. This latter area was used to disperse fighter aircraft seen on the field in March and April, 1942.

The prevailing wind in the dry season (April to November) is from the northeast, and in the wet season (December to March) is from the northwest.

Communication with Dilli town is by the main coast highway and by the old Dilli-Aileu road, each of which, in this area, is a good M.T. road.

Beach landings can be made about 3/4 mile (1 km.) to the west of the airdrome, which is then approached through coconut and banana plantations between the coast and the main road. A.F.V.'s [Armoured Fighting Vehicles] may approach through this area with fair cover.

Both Australian and Japanese troops have already landed on the beach and made the above approach to the airdrome. In view of this, there might be certain advantages in landing further to the West between the Comoro River and Tibar. The approach from here by A.F.V.'s must be made along the coast road until the Comoro River is reached or tropical undergrowth and cactus make the area most difficult for A.F.V.’s. This area is enclosed by the mountains to the South and spurs running to the coast at Tibar and to the west of the Comoro River.

The Dilli coastal area from Hera to the west of the Comoro River is also enclosed by a ridge of mountains running parallel to the coast south of Dilli, with spurs running to the coast at Cape Fatu Cama and to the west of Comoro River. A good foot and pony track runs along the top of the range from Remexio to Lau-Lora and overlooks the whole of the Dilli area. Spurs of the range run as close as 1,000 yards to the airdrome, O.P.'s were established by Australian troops in these spurs. Lau-Lora is reached by a good track leading up the mountain from the Comoro Valley just south of Comoro village. [4]

SIGNIFICANCE

Control of the Dili airfield by the Allies and the denial of its use by the Japanese was the main justification for the landing of the No. 2 Independent Company and Dutch troops in Dili on 17-20 December 1941 without the approval of the neutral Portuguese colonial administration. The airfield was in flying range of north-western Australia and enemy aircraft based there would also threaten vital shipping routes serving that region. [5]

If deterrence by the Australian-Dutch presence did not dissuade the Japanese from attacking the airfield, then it was decided to defend it for as long as was practicable against what were anticipated to be overwhelming odds and then blow up the runways with pre-laid demolition charges. This was what actually happened when the Japanese landed in Dili on 20-21 February 1942. [6]

The destruction of the runways was a temporary inconvenience for the Japanese who through pre-invasion reconnaissance and intelligence reports we well aware of the airfield’s deficiencies – it was a low-lying, boggy and subject to flooding. Soon after taking control of Dili they put into effect plans to extend the airfield on dryer land further to the south on the other side of the Dili-Tibar road as described in the ASPT. [7]

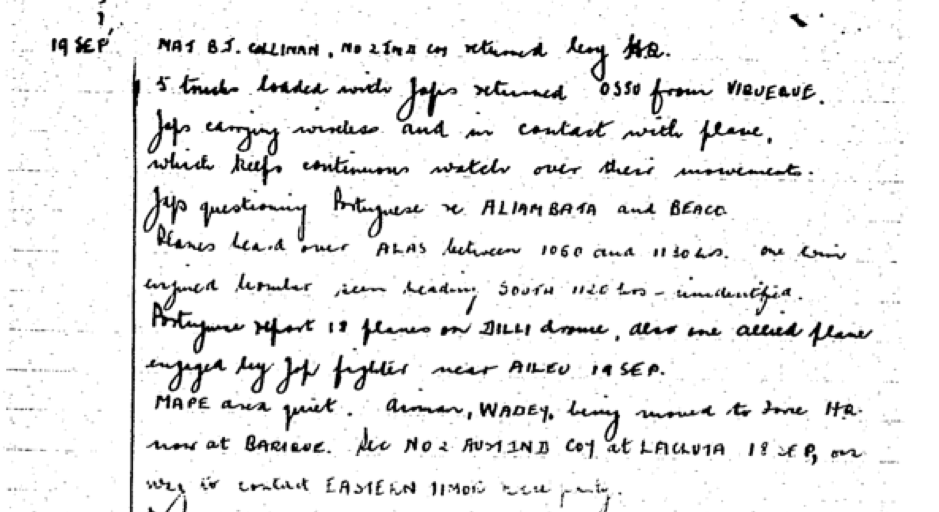

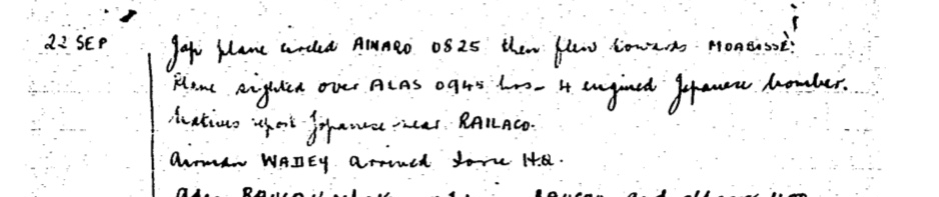

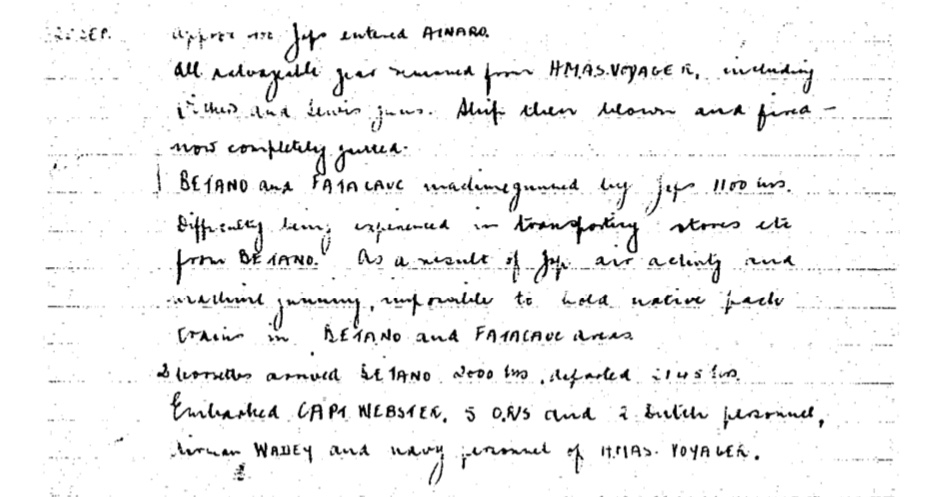

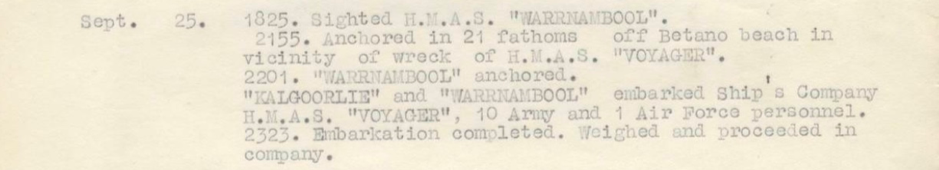

For the remainder of the Timor campaign Japanese activity and operations at the airfield were recorded and reported on by No. 2 and No. 4 Independent Company soldiers from observation posts located on the eastern and western outskirts of Dili. These reports often resulted in Australian or American bombing raids on the airfield.

CALLINAN AND TURTON’S AIRFIELD RECONNAISSANCE – MARCH 1942

When Mr David Ross, the Australian Consul at Dili who had been held captive there by the Japanese, was sent to seek out the guerrillas with demands for their surrender, he was amazed to find them in good heart. The senior officers of the Company had gathered at Hatu-Lia to meet him on 16th March. He gave to each of them a note saying that any orders for food or other commodities signed by that officer would later be honoured by the British and Australian Governments. He also gave them detailed information regarding the defences of Dili and the near-by aerodrome to aid them in raids they were planning. He took back with him to Dili their scornful refusal to surrender.

After Ross set off on his return to Dili, having given the Independent Company officers details of the Japanese defences at the aerodrome and around Dili, Captain Callinan's thoughts turned to a raid on the Japanese positions around the aerodrome. Callinan, who was a bold leader as well as an excellent tactician, decided the best way to concoct a plan was by personally going to Dili to carry out observations of the Japanese positions and movements. Accompanied by the company's engineer officer, Lieutenant D.K. Turton, Callinan set off from Hatu-Lia a few days after Ross. After stopping overnight at Railaco, where they salvaged some explosives left behind in the company withdrawal, they arrived late the next day at a small village [Beduku] on a ridge above the Comoro River, a short distance from the aerodrome.

Looking towards the hill village of Beduku from the heliport – May 5 2019

Moving the following day to a nearby village Callinan and Turton were fed and assisted by friendly Timorese who were caring for a Dutch native soldier who had escaped from Dili. This soldier and a friendly Chinese trader were questioned at length by Callinan. Neither was able to speak English, but with his slight knowledge of Malay and frequent recourse to an English-Malay dictionary, Callinan was able to obtain, by painstaking questioning and use of a sketch map, detailed information of the Japanese dispositions around Dili and at the aerodrome.

Callinan and Turton then moved to a carefully selected observation post from which they could watch the aerodrome. For several days they noted the Japanese defences and made plans for a raid on the airfield, awaiting the arrival of Lieutenant Dexter whose section was to carry out the attack which had been fixed for the last night of March. After Dexter's arrival Turton returned to Railaco to collect his sappers in order to rehearse the attack. However, before the arrangements could be completed orders arrived from Company Headquarters that the raid had been called off. Callinan's disappointment was intense. At first he contemplated turning a Nelsonian blind eye to the orders and carrying out a small raid at once, but then decided that it would be better to pull out as ordered and to return later to carry out a properly planned, large-scale raid. However, the opportunity was lost, and no raid on the aerodrome ever eventuated. [8]

Airfield plan prepared for Callinan and Turton’s report on their reconnaissance

POST WWII

Post WWII the airfield continued in use by the Portuguese administration until it was replaced by the new airfield, now named after President Nicolau Lobato, a little further west and closer to the sea front at Comoro.

The old airfield was not suitable to receive international flights that instead landed at the longer airfield at Baucau. Incoming passengers were then transhipped to Dili on smaller aircraft. This was the route followed by the 2/2 contingent that attended the opening of the Dare Memorial Pool and Resting Place in September 1969. [9]

1960s view of the airfield hangar and control tower

Heliport - hangar and control tower – 5 May 2019

After the opening of the Nicolau Lobato airfield during the Indonesian era, the section of the old airfield closest to the terminal and control tower were utilised as a military heliport.

The Australian connection with site was re-established at the beginning of the INTERFET peacekeeping operation:

On 21 September [1999] HMAS Jervis Bay delivered the Third Battalion the Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR) to Dili port and HMAS Tobruk landed twenty-two ASLAV 8 x 8 armoured vehicles of C Squadron 2nd Cavalry Regiment (C Sqn 2 Cav). On the same day twelve Black Hawk helicopters self-deployed into Dili heliport to provide tactical mobility, and A Company Second Battalion, Royal Gurkha Regiment, secured the UNAMET compound. The atmosphere of that early deployment can only be described as tense. Coalition troops fanned out to secure positions in the smoky haze that covered the city and were shocked by the devastation that they encountered. [10]

During this period the Response Force was established at the Dili heliport with 5th Aviation Regiment elements and primarily conducted reconnaissance missions, not in the classical long-term surveillance/reconnaissance mission sense, but more overt, vehicle-mounted operations.

Once forces were lodged and established, the command element of the Response Force was co-located and established with Major General Cosgrove's headquarters in the Dili Public Library. The main tasking undertaken by the Response Force throughout the INTERFET operation was as follows.

Special Forces provided the INTERFET Ready Reaction Force (RRF) with 5th Aviation Regiment helicopters and crew based at the heliport at Dili on thirty minutes notice to move. This tasking was maintained throughout the duration of the INTERFET campaign and fortunately was required to be deployed on only a handful of occasions. [11]

Heliport entrance control post – 5 May 2019

REFERENCES

[1] David Horner. – Blamey: The Commander in Chief. – Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1998: 386-387.

[2] Allied Forces. South West Pacific Area. Allied Geographical Section. Area study of Portuguese Timor / Allied Geographical Section, South West Pacific Area: The Section [Brisbane], 1943. https://repository.monash.edu/items/show/26455#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0

[3] http://arrow.monash.edu.au/hdl/1959.1/1202293. Note, as portrayed in the previous map, the current Dili Heliport occupies the same area and has the same alignment as the Japanese built extension to the old Portuguese airfield portrayed here.

[4] ASPT: 1-2.

[5] ‘75 years on: The Australian and Dutch Landings at Dili 17-20 December 1941’ https://doublereds.org.au/forums/topic/89-75-years-on-the-australian-and-dutch-landings-at-dili-17-20-december-1941/

[6] ‘Enemy occupation Of Dili: report on events 20-21 Feb. by Lt. McKenzie’ 2nd Independent Company AWM52 25/3/2/5 - Reports, statements and maps - [August to November] 1942 https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/RCDIG1026118/

[7] The Australians were also aware of the airfield’s deficiencies but a different solution to them was recommended in a report by Johnston, Bradfield and Ross who stated ‘The aerodrome is quite satisfactory for use in dry weather for Lockheed 10 or D.H. 86 aircraft, though certain improvements at relatively small cost should be made. It is too small for Lockheed 14 aircraft. During the wet season, December to March, however, the ground would be soft and boggy, and to make it available for wet weather use an expenditure of £7,000 on the provision of a gravel runway would be necessary’. ‘Report on a visit to Portuguese Timor by Captain Johnston, Dr. Bradfield and Mr. Ross’ NAA: A816, 19/301/778 https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/DetailsReports/ItemDetail.aspx?Barcode=170182&isAv=N

[8] Christopher C.H. Wray. - Timor 1942: Australian commandos at war with the Japanese. – Hawthorn, Vic.: Hutchison Australia, 1987: 90-91. Fuller accounts of Callinan and Turton’s airfield reconnaissance can be found in:

Bernard Callinan. - Independent Company: the Australian Army in Portuguese Timor 1941-43. – Melbourne: Heinemann, 1953 (repr. 1994): 74-83.

Cyril Ayris. - All the Bull's men: no. 2 Australian Independent Company (2/2nd Commando Squadron). – Perth: 2/2nd Commando Association, c2006: 203-208.

C.D. Doig. The history of the Second Independent Company. C. Doig [Perth, W.A.] 1986: 76-83.

[10] Alan Ryan - ‘Primary responsibilities and primary risks’: Australian Defence Force Participation in the International Force East Timor. - Land Warfare Studies Centre - Study Paper No. 304: 84.

[11] East Timor intervention: a retrospective on INTERFET / edited by John Blaxland. – Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2015: 116.

PREPARED BY: Ed Willis

29 November 2019

-

Thanks for your reply Sky and your impressive Google Earth presentation

-

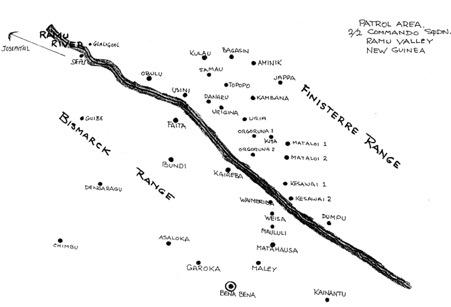

Commando Campaign Site Survey Project

Completing the remaining survey work

Perhaps even the grandchildren, or your sons and daughters one day will follow in your footsteps in Timor Leste? To be walking the hills together seeing those places where, as young commandos with your Timorese companheiros you fought the enemy, will be a grand tribute to honour our wartime generations.

Letter from Francisco Xavier do Amaral (1937-2012), first President of East Timor to Jack Carey, 2008

1. Promoting pilgrimage tourism to help the Timorese people

If you have a family or other personal connection to the 2/2, travelling to Timor-Leste for a holiday can be a very direct way to remember and honour a former 2/2 soldier. By visiting Timor-Leste, you also provide an important benefit to the Timorese people, in that you provide a much-needed stimulus to the local economy.

The country is spectacular, and the people today are much like those wonderful people Timorese our soldiers knew – open, friendly, welcoming and helpful. Most Timorese speak fondly and with reverence about the men who were “criados” or others who provided such vital assistance to the Australians during WWII.

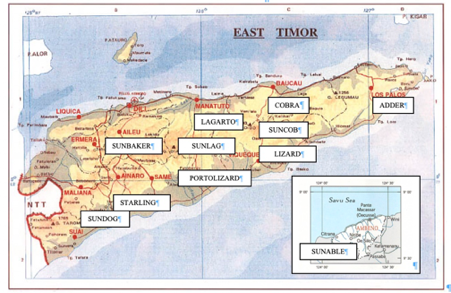

2. Commando Campaign Site Survey Project

The 2/2 Commando Association of Australia has been working on a project to survey and record information about sites connected with the commando campaign against the Japanese on Timor during 1942-1943.

Those travelling to Timor-Leste to visit sites connected with the military campaign of the 2/2 and the 2/4 on Portuguese Timor would benefit greatly from better documentation and identification the locations of those sites.

Relevant sites include:

- places where significant actions were fought against the Japanese, such as ambush sites (eg: Lahane, Nunamogue and near Remexio where the Singapore Tiger was killed);

- places where 2/2 men were killed in action (eg: ration truck massacre, the old airfield, Bazar Tete and Liltai); and

- villages and postos where the 2/2 and 2/4 were based (eg: Cactus Flats, Three Spurs and Vila Maria).

There are a number of potential sites, some of which can be accessed by vehicle and others only by trekking. It is intended to have all such sites documented in a standard and succinct way. This will include each site’s name, location (GPS coordinates), relevant history, with ready access to other information such as maps, photos, local contacts etc.

The availability of such information will enable those wishing to visit these sites on an organised tour or travelling independently to readily locate them and be better able to appreciate their history and significance.

We are documenting these sites and will make the information publicly available through the Doublereds website (doublereds.org.au) and possibly by publishing a guidebook and releasing an app for smart phones and tablets.

The site information provided could also be used to:

- devise itineraries for driving tours; and

- plan trekking routes, including those based on actual journeys undertaken during the commando campaign (eg: the Winnie the War Winner Trek, the Sid Wadey Rescue Trek and the Timor Escapees Trek. [1]

An example of the type of site documentation to be made available as an outcome of this project is that provided about Bazar-Tete and Ermera on the Doublereds website. [2]

More documentation for other sites that have been surveyed will be progressively added to the Doublereds website.

The aims of the project are:

- to economically assist Timor-Leste by encouraging tourists with a connection to the 2/2, 2/4 or Z Force, or those with a more general interest in WWII history and heritage, to visit the country; and

- to foster greater awareness of the exploits of our soldiers and the invaluable support that they received from the Timorese people.

Survey work to date has been completed by committee members voluntarily, with some funding provided by the association.

3. Remaining survey work to be done

There are 270 sites listed in the Gazetteer included the ‘Area study of Portuguese Timor’ (1943). [3]

- 117 sites have been identified as ‘Key’ and worthy of being surveyed and documented because of their being mentioned in the unit and campaign histories, war diaries and personal accounts.

- 31 Key sites have been surveyed and are being documented.

- 86 sites and a few others not listed in the Gazetteer remain to be surveyed and documented.

- Several key sites are difficult to access because of their locations in remote and mountainous terrain.

4. Itinerary of sites to be surveyed

The following table lists the key sites to be visited, in order of a direction of travel heading south-west to begin with and then working back east, moving through the central part of the island then investigating the eastern end of the island before heading back to Dili along the north coast over a four-week period.

1

Nasuta

23

Lebos

45

Maubere

67

Baucau

2

Three Spurs

24

Fatu-Lulic

46

Turiscai

68

Calicai

3

Railaco

25

Fatu-Mean

47

Fatu-Maquerec

69

Baguia

4

Liu

26

Foho-Rem

48

Punar

70

Iliomar

5

Taco-Lulic

27

Tilomar

49

Laclubar

71

Lore

6

Gleno

28

Maucatar

50

Cribas

72

Jaco

7

Ermera

29

Lebos

51

Soibada

73

Tutuala

8

Ai-Fu

30

Cumnassa

52

Fatu-Berliu

74

Com

9

Fatu-Bessi

31

Suai

53

Ailalec

75

Fuiloro

10

Vila-Maria

32

Beco

54

Mindelo

76

Lautem

11

Talo

33

Rai-Mean

55

Alas

77

Laivai

12

Hatu-Lia

34

Lias

56

Same

78

Laga

13

Tata

35

Hatu-Udo

57

Betano

79

Vemasse

14

Lete-Foho

36

Mape

58

Fatu-Cuac

80

Laleia

15

Atsabe

37

Cassa

59

Manu-Fai

81

Manatuto

16

Cailaco

38

Suro

60

Quelan River

82

Laclo

17

Marobo

39

Ainaro

61

Barique

83

Metinaro

18

Rita-Bau

40

Montassi

62

Lacluta

84

Hera

19

Bobonaro

41

Nunamogue

63

Viqueque

85

Remexio

20

Maliana

42

Aituto

64

Beasso

86

Liltai

21

Memo

43

Hatu-Builico

65

Ossu

22

Lolotoi

44

Maubisse

66

Venilale

- The itinerary must be flexible, so that each site can be properly investigated and documented without the obligation to be at a set location at the end of each day

- Food and meals would be purchased as required along the way.

- Accommodation would be utilised at hotel and guest houses when available. Survey participants would camp out at other times.

Map of itinerary of sites to be surveyed

5. Support needed to complete remaining survey work

Funding will need to be sufficient to cover the cost of a four-week research survey, conducted during the dry season, to allow the remaining survey work to be completed.

Costs will include air fares, accommodation, meals, vehicle hire, fuel, guide/interpreter, mobile phone calls and data, etc.

The survey would be best undertaken later in the dry season (July to September), when land is drier and therefore more stable and accessible. Access to some sites can be made difficult by the steep and rugged terrain and by muddy road and track conditions.

Some sites may only be accessible in the final stages on foot or, where practicable, as a motorbike pillion passenger.

6. Can you help?

The association is seeking donations that for the costs of completing the remaining site survey work. A target of $20,000 has been set for the project.

Your contribution can be made using the Doublereds ‘Donations’ page and completed using ‘Commando Campaign Site Survey’ link located there:

https://doublereds.org.au/donations/

Any donation, great or small, would be greatly appreciated.

7. References

[1] See ‘The Sid Wadey Story – Rescued On Timor’ https://doublereds.org.au/forums/topic/207-the-sid-wadey-story-–-rescued-on-timor/?tab=comments#comment-370;

‘75 Years On – “Winnie The War Winner” – Mape, Portuguese Timor - April 20, 1942’ https://doublereds.org.au/forums/topic/106-75-years-on-winnie-the-war-winner-–-mape-portuguese-timor-april-20-1942/?tab=comments#comment-163;

‘Escape From Timor – How Four Men Made It Back To Darwin After The Japanese Invasion of Portuguese Timor – Arnold Webb's and Des Lilya's Stories’ https://doublereds.org.au/forums/topic/218-escape-from-timor-–-how-four-men-made-it-back-to-darwin-after-the-japanese-invasion-of-portuguese-timor-–-arnold-webbs-and-des-lilyas-stories/?tab=comments#comment-399

[2] ‘Commando Campaign Sites – East Timor - Ermera District – Ermera’ https://doublereds.org.au/forums/topic/217-commando-campaign-sites-–-east-timor-ermera-district-ermera/;

‘Commando Campaign Sites – East Timor - Liquiça District - Bazar-Tete’ https://doublereds.org.au/forums/topic/214-commando-campaign-sites-–-east-timor-liquica-district-bazar-tete/

[3] Allied Forces. South West Pacific Area. Allied Geographical Section. Area study of Portuguese Timor / Allied Geographical Section, South West Pacific Area: The Section [Brisbane], 1943.

https://repository.monash.edu/items/show/26455#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0

Captain David Dexter of the 2/2 was seconded to the Allied Geographical Section to compile this publication. It is an invaluable primary resource for the Timor campaign containing descriptions of towns, postos, roads, tracks plus maps, town plans, photos and most significantly for this exercise a ‘Gazetteer of Towns and Villages in Portuguese Timor’. A useful adjunct to the gazetteer is a map showing all the listed towns and villages and the roads and tracks connecting them.

Prepared by Ed Willis

Vice-President, 2/2 Commando Association of Australia

Revised: 11 November 2019

-

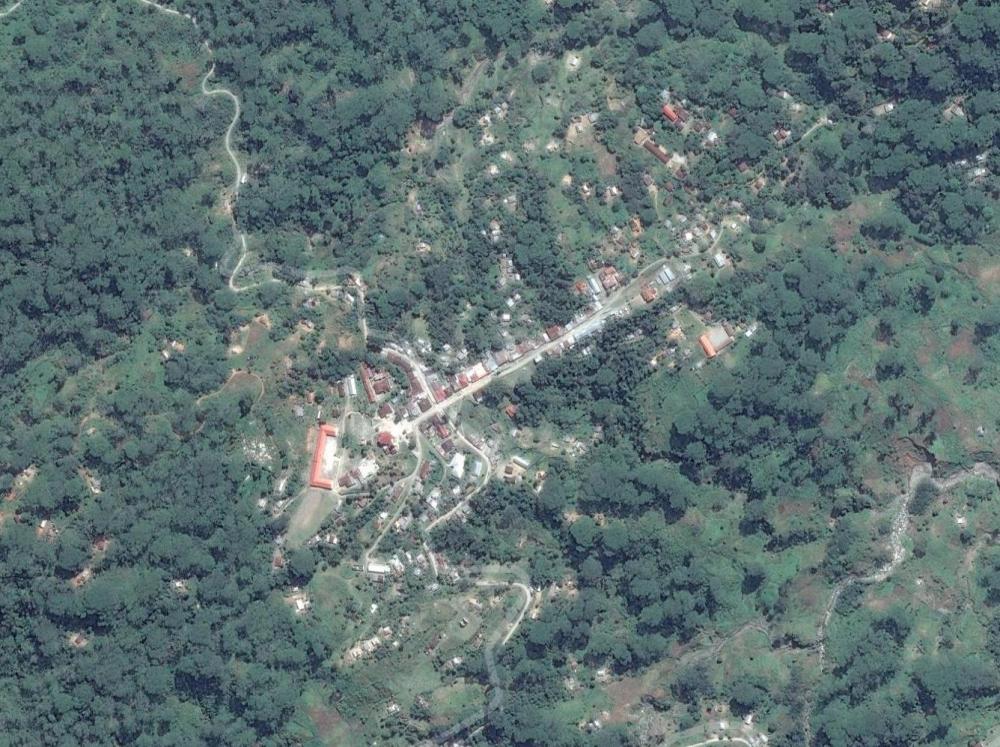

COMMANDO CAMPAIGN SITES – EAST TIMOR

AINARO DISTRICT

AINARO

GPS: 8°59′49″S 125°30′18″E

Ermera’s location from map in Area Study of Portuguese Timor (1943) [1]

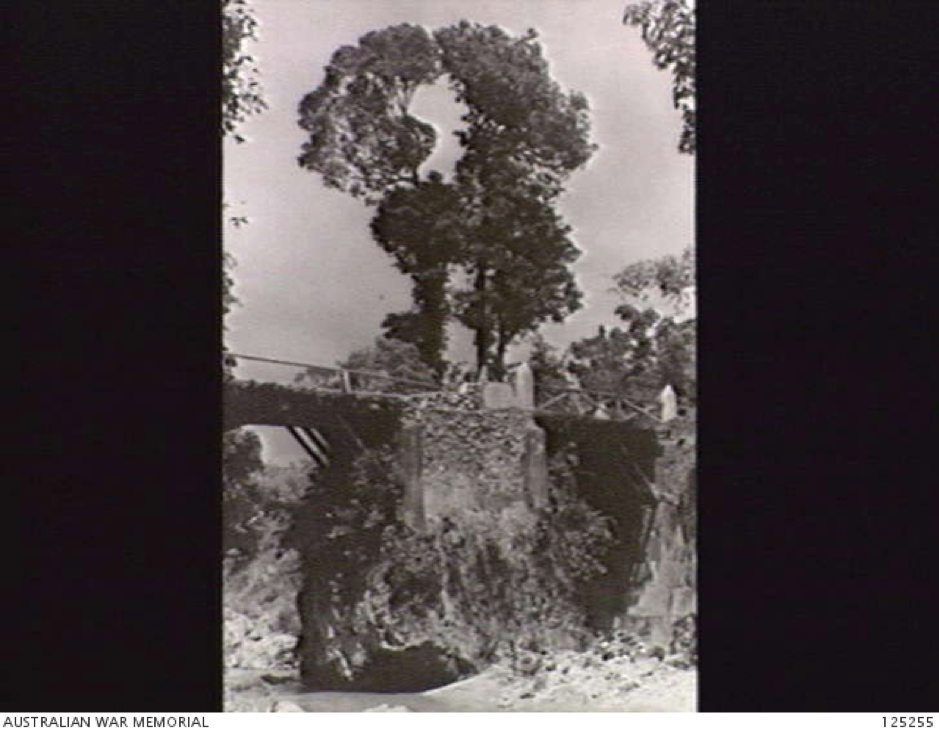

The Area study of Portuguese Timor also describes the town. The street layout is still extant as are several of the buildings indicated on the following map:

"Ainaro (see Map No, 15): Also stated to be known as Suro, but no confirmation as to whether this is correct. Ainaro is 20 miles (32 km.) south of Aileu at a bearing of 192°. A large town with posto and market, which is held weekly. It is situated on the southern slopes of Ramelau Range and built between two tributaries of the Sue River. The posto is well constructed and surrounded by the usual stone wall. Several stone buildings such as the Governor's palace, administrative block, Chinese shops, church with large spire, priest's residence and uncompleted schoolhouse, hospital and annex, etc. constitute the town. The streets are well constructed and an old road leads to Maubisse. This road was suitable for M.T. A concrete bridge was demolished by Australians as a roadblock in 1942 and approaches have been washed away. The road is now in general disrepair". [2]

Map of Ainaro (1943) [3]

Ken Piesse of the 2/4th described arriving in Ainaro in September 1942:

"Next day, with Bob Palmer's Section, we trudged past the maize and coconut plantations, up and down the hills, before finally reaching Ainaro, a really charming, beautiful spot in the centre of a rich area. What a Garden of Eden! Strawberries, sugar cane, mangoes, paw-paws, tomatoes - all kinds of vegetables. Reaching there, we sat down almost immediately to a sumptuous meal, fit for a king. We wondered how many more we would enjoy like that one.

Ainaro has a characteristic common to many Portuguese towns - its streets are paved with bricks. Harry and I would go up each morning to the top of the town where a little bridge, erected in 1936, allowed a rushing stream to pass underneath a roadway. There a quick wash refreshed us before breakfast. In the evening a large waterhole in the river some 500 yards below the 'palace' served our washing requirements well. The 'palace', where David Dexter's HQ was located, was the home of the King of Ainaro, prior to the Japanese infiltration south of the Ramelau.

Mighty Ramelau towered 10,000 ft above Ainaro. Its sheer slopes were separated from the pretty little town, complete with a red-roofed church, by only a mile of irrigated rice fields. The rice cultivation outside Ainaro was the biggest I had seen. Their orderly terraces were a pleasure to see". [4]

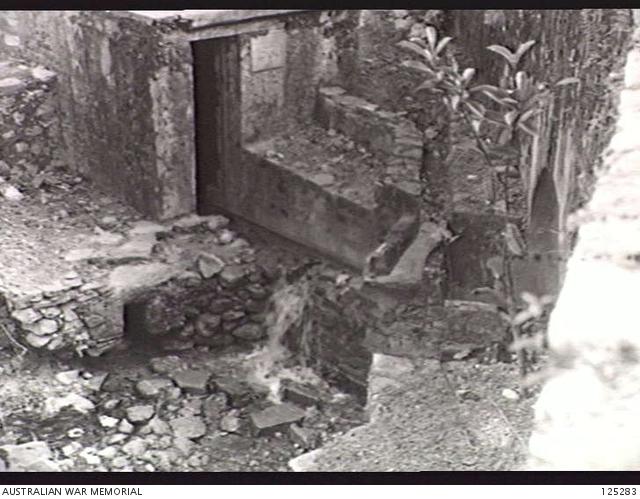

AINARO, PORTUGUESE TIMOR. 1946-01-24. THE AUSTRALIANS OF SPARROW FORCE USED THIS SMALL WATERFALL AS A WASHING PLACE DURING THEIR OCCUPATION OF THE TOWN IN 1942.

Callinan also described the town around that time:

"At Ainaro was established a base for the treatment of sick personnel. In addition to the company's sick there were many men from Koepang who were still ineffective for one reason or another. Ainaro was placed under the control of Captain Dunkley (Company medical officer) and was ideal for our purpose. The town itself was the oldest post in the island, having been one of the early missionary centres. It was well laid out and had some fine houses and a hospital which was taken over by us. In peace time it had been used as a summer residence by the Governor, and his residence became the officers' quarters. In addition, it was a rich area peopled by friendly Christian natives, and the Chefe de Posto was most helpful and could speak good English". [5]

Later on he provides this additional description:

"The town was laid out in neat cobbled streets with a small park in the centre, on to which opened the house and offices of the Chefe de Posta as well as the summer residence of the Governor". [6]

SIGNIFICANCE

The town of Ainaro was strategically important throughout the Commando Campaign being located on the main through route heading south from Dili through Aileu and Maubisse towards the southwest strongholds of Mape and Bobonaro. Once there, a track could also be followed through Hatu-Udo to the south coast landing place of Betano.

By mid-May 1942 Sparrow Force Headquarters was at Mape, with the Independent Company Headquarters located at Bobonaro. A Platoon, then commanded by Lieutenant Dexter, was dispersed between Marobo and Cailaco while Laidlaw's B Platoon was still at Remexio, covering the environs of Dili. Boyland's C Platoon was at Maubisse. Another platoon, initially called K (Koepang) Platoon, but subsequently D Platoon, was being raised from troops from Dutch Timor who had completed training. This incomplete platoon was initially based at Memo.

Recent aerial view of Ainaro – Bing Maps

As part of the reorganisation of the Australian forces, the hospital under Captain Dunkley had been moved to Ainaro, an old missionary town which in peacetime had housed the governor's summer retreat. In addition to providing hospital care for the sick, troops from Koepang were placed in training squads. Under the guidance of non-commissioned officers and selected privates from Independent Company sections the Koepang troops received basic infantry training followed by a grounding in Independent Company work and then became members of the new D Platoon under the command of Lt Don Turton. Callinan recorded that:

"Through Ainaro passed representatives of nineteen different units including all arms of the service and many specialist units, postal, dental and similar. Also men such as refrigerator specialists, bakers and butchers. Many of these had received no infantry training what- soever and some of them were aged over fifty. Ainaro did much to rehabilitate many of the men who had come to us, and afterwards they gave good service" [7]

The newly formed D Platoon went into action for the first time on 15 June 1942. Dr Dunkley’s hospital was relocated from Ainaro to Same in mid-August – the latter town was deemed to be a more secure location at that time.

Map of Dili, Aileu, Maubisse Region [8]

VISITING AINARO TODAY

Road Conditions in 1942

The Area study of Portuguese Timor (1943) describes the terrain traversed by the road between Ainaro to Maubisse via Aituto in a manner that is still relevant today:

"AINARO TO AITUTO TO MAUBISSE:

Distance 17 miles (27 km.). Time taken, 81/2 hours.

This track, along which many actions have taken place, is really an old road too much in disrepair to be claimed as a road. It crosses some of the most rugged country on the island. There is very little cover throughout the route. From the thickly populated mission centre of Ainaro the track winds up to the saddle of the Suro Range from which the Maubisse Valley can be seen. The track then winds steeply down and crosses a rapid tributary of the Be-Lulic River. With the huge mountain spurs of the Ramelau Range to the northwest, and of the Cablac Range to the southeast, the track winds precipitously along the right side of the Be-Lulic gorge crossing many streams until Aituto at the junction of the Maubisse-Ainaro and Maubisse-Same tracks are reached.

From Aituto the track winds round a big range up to the Maubisse Saddle and then descends steeply across the Carau-Ulo River into the posto of Maubisse. Because of its nature this track from Ainaro to Maubisse has been the scene of some our most successful Australian ambushes of the Timor campaign". [9]

Callinan as so often, can be relied on to provide a description of the terrain in 1942 that can also be readily applied to today:

"The Portuguese had constructed a number of roads throughout the colony. The north coast road was trafficable, as were portions of the other roads; but, as we knew the inland roads, they were hopelessly cut about by landslides and the ravages of torrents. All the roads were splendidly graded, and the mind retains a vivid picture of such roads as that between Ainaro and Maubisse in steep sidling country winding with a tantalizing regular grade for mile after mile, back into chasm-like gullies and out around precipitous spurs. Grade and windings alike seemed interminable". [10]

Dili-Ainaro driving directions - MapQuest

Road Conditions Today

The road from Dili to Ainaro has been substantially upgraded over the last five years through a major infrastructure project funded by the World Bank and can be transited by car in comfort. Rehabilitation work to complete the final section of the Dili to Ainaro road corridor in Timor-Leste has started - the project will upgrade the 22.6 km Laulara-Solerema section of the 110km road corridor. [11]

The completion of the project will be an important milestone in one of the most significant transport projects ever undertaken in Timor-Leste, and will help to ensure safer, faster and more reliable travel between the North and the South of the country -- connecting the districts of Dili, Aileu and Ainaro, which jointly account for a third of the country’s population.

Timor-Leste is vulnerable to extreme weather with heavy rain and landslides damaging roads and bridges, and accelerating wear and tear on vital infrastructure. The Dili to Ainaro roadworks feature improved drainage, construction or reinforcement of slope stabilization, and pavement rehabilitation and were done with a focus on future resilience to the effects of weather and natural hazards. In addition to the road construction, the World Bank is working with the United Nations Development Program to equip local communities with the skills and knowledge to better manage the effects of natural disasters and weather events along the Dili-Ainaro Road Corridor.

About 25 kilometres south of Maubisse, the road tops out over a ridge at Flecha with spectacular views of the Ramelau range to the west and forks with the left heading to Same in Manufahi district and the right, which leads to the district capital of Ainaro. There are fantastic views here, east down into the deep valley of the Belulie River, and across to the Cablaque Range.

Recent Description of Ainaro

The rural town of Ainaro is the administrative capital of Ainaro district and Ainaro sub- district. It is located within the administrative boundaries of the village (suku) of Ainaro. The village of Ainaro is composed of seven hamlets. Of these Hatumera, Lugatu and Teliga are considered to be 'mountain' (foho) or rural hamlets, while Ainaro, Sabago, Builco and Nugufu constitute the bulk of Ainaro town.

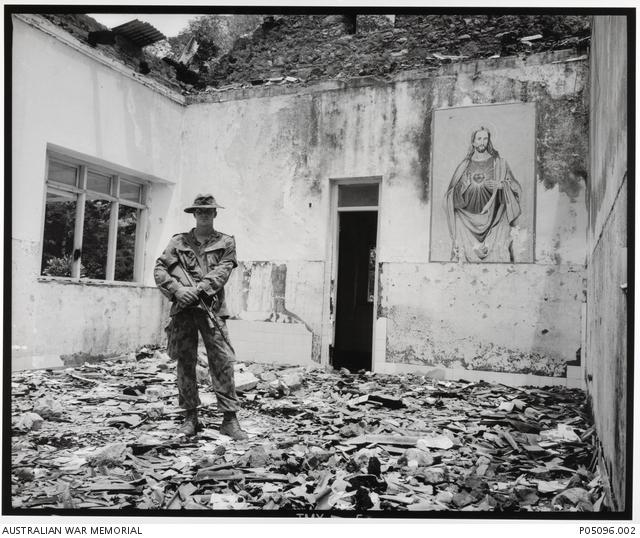

An unidentified Australian soldier in the remains of Ainaro Hospital. Ainaro is a mountain town in the southwest of East Timor. The town was hit hard during the civil unrest that occurred throughout 1999 and 2000, when its health clinics, hospital and schools were all levelled by militia groups.

Ainaro town was almost completely destroyed in 1999 by pro-autonomy militia and elements of the Indonesian military. Practically all public buildings including the district hospital were destroyed; the Catholic mission school, Canossian residence and almost 80 per cent of all private dwellings were also burnt and looted. Many of the inhabitants of Ainaro town fled or were forcibly displaced to West Timor; others sought shelter in the surrounding hills and mountains. While the majority of East Timorese former residents of Ainaro have now returned, or resettled in the capital Dili, some remain in West Timor or elsewhere in Indonesia and many non-East Timorese former residents, including Indonesian civil servants and business people, have not returned and are not expected to return.

Portuguese era market, Ainaro – 27 April 2014

Although the rehabilitation and reconstruction of basic infrastructure in Ainaro town has been slow, a number of public services now are available. There are two public primary schools, a public pre-secondary and secondary school, an out-patient health clinic, a hospital, and a police station. In 2007, the town water supply and electricity were also rehabilitated. The town market and abattoir is in the process of being refurbished and housing for the local police is also being built. The district and sub-district administration continue to occupy buildings rehabilitated during the UN Transitional Administration.

While a number of local residents are employed as public servants, the majority are engaged in various forms of subsistence farming. Households farm a variety of crops including maize, beans, potatoes and root crops in swidden gardens on land surrounding Ainaro town. Permanent and seasonal fruits and other market vegetables are often grown in house plots or uncultivated areas of land in and around Ainaro town. A number of households have access to rice fields to the south of the town, near the neighbouring village of Cassa, or to the east near Manutasi. Many households also cultivate coffee in small plantations in upland areas. It is common for households to keep pigs and chickens; only a limited number graze cattle in upland pastures.

There are two markets in Ainaro town. The first is located close to the old town centre and was originally built during the Portuguese period. The second, larger market is temporarily located in the 'new' town close to the Indonesian-era district administrator's office, which is currently being rebuilt. Saturday is the main market day in Ainaro, and people travel from surrounding villages, sub-districts and districts to buy and sell their produce. There are also a number of shops in town selling a wide variety of manufactured goods. Many of these shops are owned and run by Chinese-Indonesian or Chinese-Timorese.

The size and composition of Ainaro town has changed considerably over time. Today, Ainaro village has a population of 6,937 people, the majority of whom live in Ainaro town (Census 2010). This accounts for approximately 45 per cent of the total sub-district population. The population of Ainaro town rose rapidly in the aftermath of the Indonesian invasion as communities were displaced from remote areas and resettled closer to military installations and administrative centres such as Ainaro town. Since independence, the rate of return to remote areas has been relatively slow with larger numbers of people continuing to migrate from rural areas to urban areas. While a small proportion of the current population includes persons displaced from Dili in the aftermath of the political violence in 2006, the most common reasons for moving to urban areas since independence are access to education and employment opportunities (Census 2010). [12]

There are a few significant remnants of the town as it is existed in 1942 that can be seen when visiting.

Portuguese Memorial to Dom Aleixo Corte Real

In the central part of town there is a substantial Portuguese war memorial, the provenance of which has been well described by Geoffrey Gunn:

"Another surviving reminder of the Japanese occupation is the less elaborate but no less compelling – even elegant – monument in Ainaro to Dom Aleixo Corte Real, the quintessential loyal Timorese chief killed by the Japanese in May 1943) …. Taking the form of a simple stone arch offering a large open window space into which a wrought iron cross is placed, the monument is headed ‘Por Portugal’ and, at the base, inscribed ‘A Memoria do Regulo D. Aleixo Corte Real, Morreu em 1943’.

Yet, from an Australian War Memorial photograph dated 24 January 1945 and taken by K.B. Davis of Sparrow Force [Negative no. 125289], this monument was preceded by a sepulchre of the royal family where the skulls of ‘King’ Aleixo and his three ‘sons’ or more likely companheiros, Alfonso, Francisco, and Alveira, were on public (?) display, albeit arranged behind a crucifix.

As Pelissier comments, the uprising by Maubisse was not out of love for the Japanese, but out of decades-old memories of the Manufahi wars, especially the quest on the part of this disaffected people in seeking revenge against rival Suro (Aileu), and its loyalists, namely Dom Aleixo Corte Real, liurai of Suro, nephew of Nai-Cau, the ‘traitor’ liuraiof the 1912 rebellion who stood with the Portuguese. Posthumously awarded Portuguese state honours, Dom Aleixo, his sons and followers, mounted a heroic but doomed stand against Japanese-led forces in the mountains of Timor in May 1943". [13]

Portuguese Memorial to Dom Aleixo Corte Real – 27 April 2014

Former Summer Residence of the Portuguese Governor

This building is a fine example of the Portuguese architectural heritage and is now being used as Timor-Leste government offices. This could be the former summer residence of the governor that was used as officers’ quarters by the 2/2nd. Bernard Callinan reminisces again:

"I've only been back once, with my wife in 1963. The Portuguese army commander made a jeep and an officer available to take me wherever I wanted to go. Fifteen years after the war, there were the postos [districts] and all the colonial officials again, the same as before. In Ainaro, a pretty town with the mountains up high behind, there's a summer residence for the Governor which had probably been there a hundred years before Melbourne had a single white person in it. There was European influence so long; the Portuguese were in Timor twice as long as the British were in India". [14]

Harry Wray became familiar with this building when back in Ainaro after the August Push:

"Well, as I have said the Japs gave up their drive as suddenly as they had commenced it and returned to Dili. Dex left the village we were in and marched down into Ainaro. That is where the Doctor had his Hospital at the time I went there to have a tooth extracted".

Former Summer Residence of the Portuguese Governor, Ainaro – 27 April 2014

"We took up our quarters in the Governor’s summer residence, a nice house complete with bathroom and all mod cons. Steps led down from the house to a cobbled road, and across the road was a rectangle of grass closely planted with huge trees. Facing the end of the rectangle of grass and trees was the Administrator’s house.

Ainaro, like Bobonaro, was the headquarters of an Administrator. The Governor of the Porto part of the island was the head of the local government. Under him came the Administrators who each governed a Province, and under the Administrators came the Comandantes who each governed a District in the respective Provinces.

The Administrator of Ainaro was absent during the close proximity of the Japs as he was known to them as friendly to the Australians. After the Japs departed from the area he returned to his house with his wife, a very pretty woman, and his young daughter. The Administrator’s house was to the left of our house, but close by. On the other side of the park like area lay the Administrative offices and jail. One Section of Dex’s men were camped in this building.

…

We had several visits early in the morning from Jap planes, but beyond flying over the place they did not attempt to bomb or molest anyone in Ainaro. The Administrator and his family never failed to come racing out to shelter. The Administrator would be in the lead in his pyjamas, next a few yards behind his pretty wife in a silk nightgown with a white silk dressing gown streaming out behind as she raced for the trench, and in the rear would come the little girl legging it for shelter. The procession would shoot out the front door, down the front path out of the gate, across the cobbled street and then for about fifteen yards across the grass under the trees to the trench, which was almost directly in front of our house. We never bothered to go the shelter and used to watch the race to the slit trench with much enjoyment". [15]

AWM 125284 - Ainaro, Portuguese Timor. 1946-01-24. The stone church at Ainaro whose towers were uses as air-raid observation posts. (Photographer Sgt K.B. Davis)

The Church in Ainaro

In Ainaro’s Catholic precinct a large church, nunnery, seminary and schools lie in close proximity. Callinan was a devout Catholic, known to some of his compatriots as “the Saint”. He recalled:

"Entering into Ainaro my attention was drawn first to the church, a large white structure with a red roof, standing away from the town. This was the missionary centre of the colony, and it was fitting that it should possess a good church". [16]

Another 2/2nd veteran, Paddy Kenneally recalled:

"I went to Mass in Ainaro for Easter Sunday 1942. The beautiful Gregorian chant of the natives' singing was wonderful …". [17]

The Catholic Church in Ainaro has been a significant building in the townscape since before WWII. Its presence is referred to in the recollections of Callinan, Lambert and Kenneally and it is referenced in the Area Study including being placed on the map of the town in its current location.

Ainaro Church, 29 July 2008

The building has a large footprint, a lofty interior and distinctive twin towers embracing the south frontage. It is a building of national significance and is undergone an extensive internal and external refurbishment that was commenced in 2013 and is still incomplete at the time of writing.

Comparison of photos from 1946, 2008 and 2014 shows that some details of the front aspect have changed over time. Earlier on the bells were not hung in the towers but positioned on rather temporary looking wooden supports on either side of the front piazza. The typically Portuguese balustrade enclosing the piazza has not been recreated in the current refurbishment that has an open fully stepped approach. As yet, the front window treatments are incomplete and don’t reflect the mix of Portuguese and Timorese traditional decoration that was featured in 2008. The final internal and external colour scheme is also not evident.

AWM 125285 - Ainaro, Portuguese Timor. 1946-01-24. Sergeant G. Milsom, Military History Section Field Team and formerly of the 2/2nd Independent Company, stands beside the grave of three Portuguese priests. Fathers Piris, Alberto and Luiz were killed because of their anti-Japanese sympathies. (Photographer Sgt K.B. Davis)

Harry Wray recalled:

"Ainaro was remarkable for an enormous church. It would have been a very large church for even a big city, but for a place like Ainaro it was immense. This church was rather like the cathedral in Dili in general design, and nearly as large. The priests looked after the church, and also ran a big mission. The natives were taught, among other things, cultivation and agriculture.

One of the priests was a small man with a bright ginger red beard and hair. He looked more like a Scot than a Portuguese. He spoke excellent English. The other and younger Father was a typical Portuguese of the plump variety, but like the senior priest, very well disposed to us.

The priests had a wireless set and allowed a few of us to call each night to hear a broadcast of the news. I was the representative of those at the Governor’s house and would go up each night to hear the news, and when I returned I had to repeat it to the other men. I can recall hearing the news of the Jap attack at Milne Bay and the defeat they suffered there, the first major reversal they suffered in New Guinea".

AWM 125286 - Ainaro, Portuguese Timor. 1946-01-24. Sergeant G. Milsom, Military History Section Field Team and Formerly of the 2/2nd Independent Company, re-enacts what was a regular occurrence during the Australian occupation of Ainaro. As Manuberi his creado or native helper points to the distance Sgt Milsom rings one of the church bells that were used to sound air raid alarms when the Japanese air force launched bombing raids on the town. (Photographer Sgt K.B. Davis)

"Sometime later the Japs entered Ainaro after a day long battle with Dex and his Platoon. The two Bren gunners who were both wonderful shots silenced the crews of six Vickers’ guns time after time, and largely helped in keeping about five hundred Japs all day. Our sixty or so men walked off after dark in good order.

It was out of the question to remain against the Japs at night, as with their superior numbers they would have surrounded our men in the dark and wiped them out at their leisure the next day.

These Japs entered Ainaro and stayed a few days, but after they had gone our men had a look around and found that contrary to their usual habits the Japs had left the place undamaged, and clean. They had not molested any of the local inhabitants in any way.

Not long after this, another large party of Japs gain visited Ainaro, after being well harassed as they passed along a narrow track on their way there. This party was just the opposite in their behaviour. A party of Dutch who were sent in to have a look around found many signs of wanton destruction, and the houses they had occupied in a filthy condition. They found and buried the remains of the two priests who had been literally hacked to pieces in their church. So it was that these two men paid the penalty for being friendly with us. They were indeed good friends to us, and we were all shocked to hear of their terrible fate". [18]

Charles Bush - Captain Dunkley's hospital, Ainaro Timor. Showing the building in which Captain C R Dunkley, Australian Army Medical Corps, the Medical Officer of 2/2nd Australian Independent Company, established a base for the treatment of sick personnel of the Company, during the guerilla operations against the Japanese in 1942. Many men of "Sparrow Force" who had not surrendered at Koepang who were still ineffective for one reason or another, were also treated here.

The Hospital in Ainaro

The current Indonesian era building was constructed on the site of the former Portuguese hospital that was used by Dr Roger Dunkley and his medical team for lengthy periods during the Commando Campaign. Col Doig recalled travelling to Ainaro to be treated by the Doctor:

"My health deteriorated rapidly at Bobanaro and pleurisy set in and my appetite deserted me completely. I was put into bed at Australia House and a Portuguese enfermeira became my kind of doctor …

Ainaro Hospital, 1938. The photo can be viewed at the current hospital

"I don't really know who decided that I had better get to see Capt. Dunkley at his hospital at Ainaro. A litter was made from poles and a blanket and a fair number of native carriers pressed into service to carry me from Bobanaro to Ainaro. It was to be a journey of at least five days. I am really not sure how long because I was in a stupor a lot of the time. The tracks in Timor are nothing short of terrible, and with natives carrying the litter over streams and gullies and up and down mountains, and I mean mountains, it was a bloody nightmare of the worst kind each day. A bit, of chicken soup was about all I could keep down.

…..

It was a further three days before I was to reach Ainaro on this horror journey. I was but skin and bone on arrival. I remember somewhere along the journey one of our cooks, ‘Frying Pan Smith’ came up on a Timor pony and was horrified to see me and offered, me a smoke which was not on. Capt. Dunkley, who was no giant, lifted me off this litter and carried me like a baby into his hospital and gave up his mattress to me for my comfort. It was to be a fairly long grind before I got back onto the track again.

Apparently in the period just before I got to Bobonaro the wonderful set 'Winnie the War Winner' had been successfully constructed by Joe Loveless and his assistants, especially Sig Keith Richards and Capt. Geo. Parker of 8th Div. Sigs, and communications had been re-established with Australia. A P.B.Y. Flying Boat had arrived and Brigadier Veale, Col. Van Straaten, badly wounded in the persons of Pte. Alan Hollow, Eddie Craighill, Gerry Maley and Clarrie Varian had been lifted back to Australia. The reason the Brigadier was at Bobanaro at the time of my outburst was to get final briefing prior to departure. By the time I reached Capt. Dunkley at Ainaro that crowd had gone to Aussie and this relieved Capt. Dunkley of these badly wounded and allowed him a bit more time for lesser fry like yours truly. So the Doctor set out to do his best for me and a big swag of sick people in his hospital".

AWM 125287 - Ainaro, Portuguese Timor. 1946-01-24. This building was taken over as a hospital by Captain C.R. Dunkley, 2/2nd Independent Company, during the period in 1942 when Sparrow Force occupied the town. The verandah was used as a mess hall. (Photographer Sgt K.B. Davis)

"It was estimated that I weighed less than six stone on arrival, and I learned many years later from Sgt. Cliff Paff that the Doc didn't give me much chance of survival, but that didn't deter him from getting on with the job. He used Friars Balsam all over the lung area as a counter irritant to reduce the fluid on the lung and get rid of the pleurisy. He said immediately that the quinine bark had been a disaster as it had brought on Black Water Fever, which was usually a fever that killed in 90% of cases. He fed me as best he could and gave me quinine to keep the malaria at bay, and fortunately I soon responded to his ministrations and started to show rapid improvement. It was a good job that the Japs had not moved to the south coast area in this time or I would have been in strife. Doctor Dunkley told me that to handle pleurisy properly he should have operated and drained the fluid from the lungs, but because of his precarious position with the hospital, he wasn't game to do an operation of this nature.

While in hospital one of my No. 5 Section in Geo. Merritt came in with something wrong with him and it wasn't long before this hard case had things going for him. He purchased a great big bag of peanuts and then had a Timorese lad shelling them and roasting them in a big pan. I can assure you a diet of peanuts and paw-paw is such that you don't need No. 9s, cascara or any other opening medicine. Dudley Tapper came and saw me and brought me up to date on the old 5 Section. He wasn't all that happy with my replacement Lt. Geo Cardy and was hoping that I would return to the Section when I left hospital. Lt. John Burridge came in on crutches with a knife wound in his foot and we had some sing songs with John leading the way as he had a good voice. Capt. Rolf Baldwin came through and he and Dr. Dunkley kept me amused telling of the pranks of their University days. Dave Ross the Australian Consul in Dili at the start of the war came through after delivering the second surrender demand message from the Japs. He looked like a scarecrow, and he was not returning to the Japs in Dili but was going to get home to Aussie on the next contact. It was here that Staff Capt. Geo Arnold told me of the Brigadier scratching my name from his list of hopefuls.

There were quite a few cases of V.D., which displeased Dr. Dunkley no end. He used to really rave when these types came in and would blast them and say, ‘You are bludging on your mates. We don't get any reinforcements, and you being here only make more patrols and guards for your mates. I'm ashamed of you’. One bloke came with the Jack, whistling. The Doc. soon took the whistle out of him. Doc Dunkley was a bit paranoid about Dutchies, he hated to see them come and hunted them as soon as he could. I have nothing but the highest praise for Capt. Dunkley; he was the real hero of the 2nd Ind. Coy, both as a doctor and as a heroic soldier. I'm afraid his services were badly overlooked when the gongs went around, and it was sad to think lesser types got good decorations for being useless". [19]

Harry Wray was also a patient at the hospital:

"After reaching the bottom of this cliff we climbed for a time and then passed over undulating country, then into low lying country and then up a cliff, but by a fairly easy path, and this took us to the top of a fairly flat tableland cover in long grass. A few miles across the tableland and we were in Ainaro, the summer residence of the Portuguese Governor of Timor.

I reported to the Doctor who told me to find space in one of the wards, and he would see me in the morning. The Hospital was actually the Portuguese Hospital, a fine building with a tile roof, two large wards, and a number of small rooms, with a spacious veranda all around the building.

I spent the night on the floor of one of the wards, and next morning went into the small room that the Doctor used as a dispensary, and as a room for doing dressings. By then he had a fair collection of drugs and dressings, but far from sufficient, so great care had to be used to avoid waste.

The Doctor told me that he had pulled his first tooth only a few days before, when he drew four for a Portuguese, he said that the Porto had complemented him on his skill as a dentist. I just hoped for the best. The Doctor called for his dental kit, this was produced, and consisted of a syringe for the injections and a set of forceps. I was sat down on a basket containing medical stores, and the Doctor gave me the injections, and pulled out the tooth as if he had been a dentist for years".

Pip (son of Dr Roger Dunkley) and Barb Dunkley in front of the current Ainaro Hospital that stands on the site of the old Portuguese era hospital – 27 April 2014

He told me that I could have that day and the next for a spell before setting off back to the Section. I was also told to shift to a house down in the town proper, which was used as a sort of convalescent depot, for the remainder of my stay. I went off to this house and found Do-Dah established there.

After my two days rest the Doctor told me I could return to my Section and said he would send a native along next morning to carry my pack for me as far as Mape.

Ainaro was full of sick, and convalescents. There were a large number of men who had escaped from Koepang there also. A training camp had been established to teach the men from Koepang some of the rudiments of guerrilla warfare. As it happened a good many of them were anything but trained soldiers. As a good many of them were batmen, orderlies, drivers and so on they had but little training and experience in drill and arms. This lack of knowledge was remedied in Ainaro, and when they had gone through a course there some were sent out as reinforcements to Sections of our own unit, and a couple of Sections formed from the remainder, and placed under the command of our officers.

There were a few officers, from Majors downwards at Ainaro all from the Koepang end. Nearly all these officers were sent back to Australia as opportunity occurred, as they were more likely to be useful there, or in units being formed there, as most of them were well up in their own special branches of the service.

Beyond an occasional Jap plane passing overhead life at that time was very peaceful in Ainaro. [20]

REFERENCES

[1] From ASPT Map 1.

[2] ASPT: 28.

[3] From ASPT Map 15.

[4] Lambert, Commando: from Tidal River to Tarakan: 92.

[5] Callinan, Independent Company: 109.

[6] Callinan, Independent Company: 126.

[7] Callinan, Independent Company: 110.

[8] ASPT Map 3.

[9] ] ASPT: 47.

[10] Callinan, Independent Company: 35.

[11] https://www.roadtraffic-technology.com/news/rehabilitation-dili-ainaro-road-corridor/

[12] Daniel Fitzpatrick, Andrew McWilliam and Susana Barnes. - Property and social resilience in times of conflict: land, custom and law in East Timor. – Oxford: Routledge, 2016: 210-2012.

[13] Geoffrey C. Gunn ‘From Salazar to Suharto: toponomy, public architecture, and memory in the making of Timor memory’ in Gunn. - New World Hegemony in the Malay World. - Lawrenceville, N.J.: The Red Sea Press, 2000: 241 – 242.

[14] Bernard Callinan ‘The best the Timorese gave us was their loyalty’ in Michelle Turner. - Telling: East Timor: personal testimonies 1942-1992. – Kensington, N.S.W.: New South Wales University Press, 1992: 62.

[15] Wray, Recollections: 182, 185-186.

[16] Callinan, Independent company: 126.

[17] John (Paddy) Kenneally “Whitewashed walls and gum trees” in Telling: East Timor … : 15.

[18] Wray, Recollections: 187-188.

[19] Doig, Ramblings of a ratbag, 91-92.

[20] Wray, Recollections: 118-120.

Prepared by Ed Willis

Revised: 9 October 2019

-

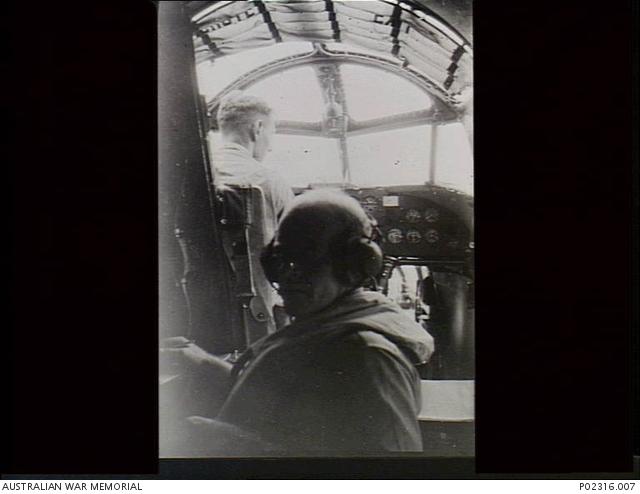

ESCAPE FROM TIMOR – HOW FOUR MEN MADE IT BACK TO DARWIN AFTER THE JAPANESE INVASION OF PORTUGUESE TIMOR – ARNOLD WEBB’S AND DES LILYA’S STORIES

Col Doig has provided a summary of this amazing adventure story that usefully serves as an introduction to this post:

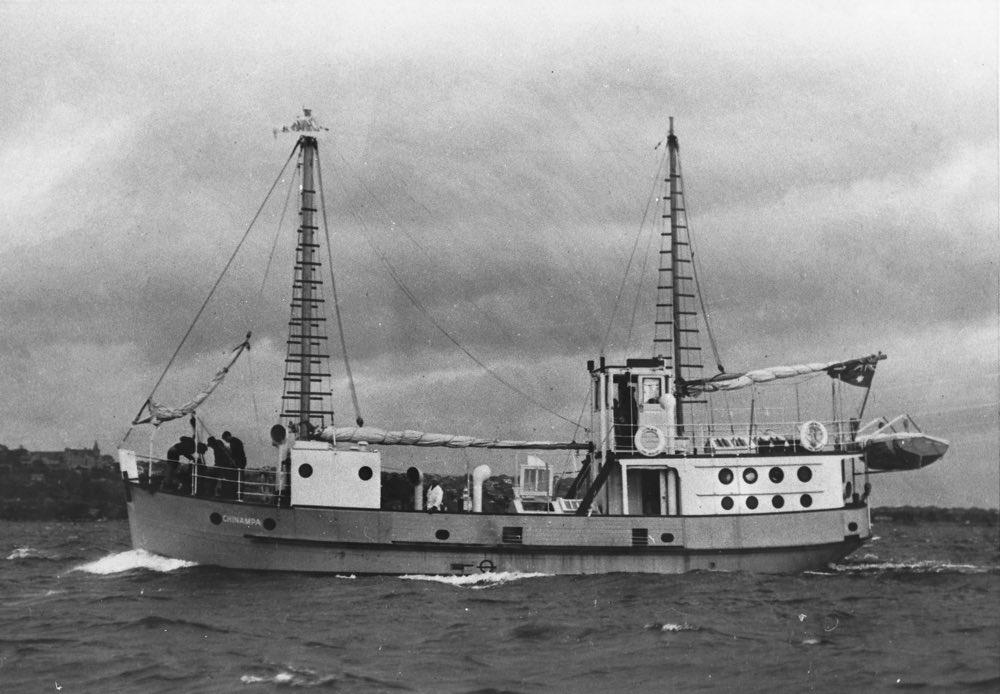

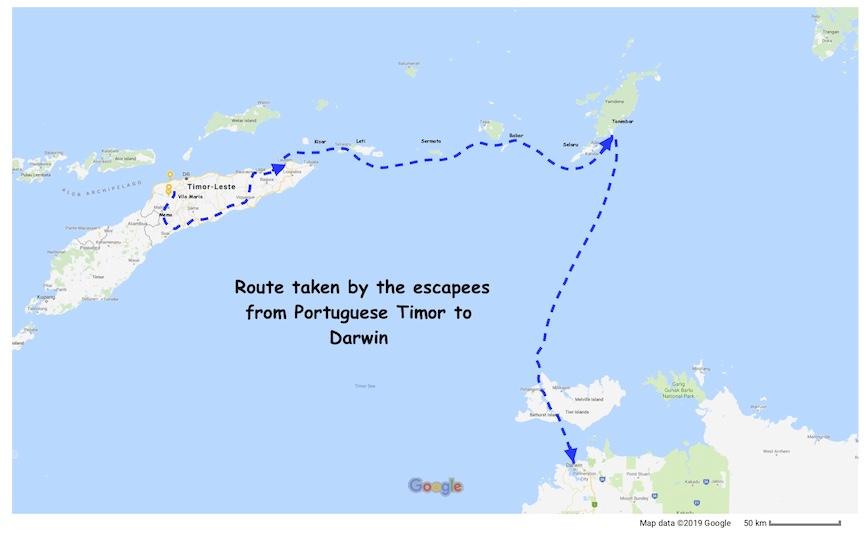

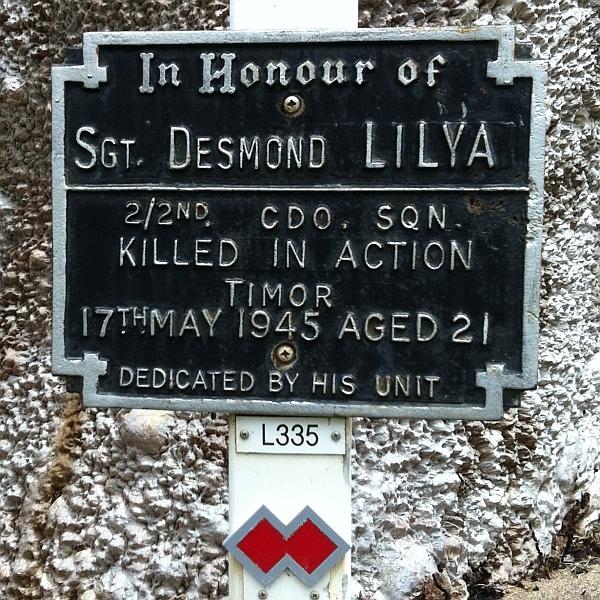

‘A party comprising certain members of the reinforcements who came on the ‘Koolama’ and who were at a loose end and not at the time attached to any of the Sections, decided to try and get to Australia by boat and advise that the 2nd Independent Coy was still intact and fighting on. This party comprised Ptes Larney, A. Webb, D. Lilya and ‘Curly’ Freeman.

They had wandered firstly to the west but were frustrated and had many adventures before heading to the east of Timor. They started their movement late in February; they ran in with a patrol of 2nd Coy who questioned them but as these boys were reo's [reinforcements] they did not know them.

Arriving at Lautem on the east end they obtained a boat going to Kisa and they made a landfall on this island and finally arrived at Leti. After many efforts they left Leti and got to the island of Moa and from there to Sermata. Here Webb got sick of the bickering and tried to drown himself and was dragged back by Freeman. They ran in with a large vessel that was probably some sort of smuggler, which took them to Teepa where they broke up. Freeman and Lilya went on their own and Webb and Larney went on their way and were eventually picked up by an Australian lugger that took them to Darwin. There they met Alan Hollow and Keith Hayes. This was the last week in May.

Their journey was in vain as contact had been made by Timor with Australia. Their treatment by Australian authorities was terrible and they were put in the worst type of boob and got it real tough. Eventually Lilya and Freeman arrived. The first two were interrogated by Intelligence who did not believe their story.

After a lot of crook treatment Webb and Larney boarded the ‘Voyager’ and were returned to Timor and Lilya and Freeman who had been sent south on leave were also brought back and went with the others to Timor where they all rejoined Sections.

This was an epic journey and the lads deserved a better fate at the hands of the Australian Administration in Darwin’. [1]

There is more to Lilya and Freeman’s travails after they separated from Webb and Larney than was recounted by Doig and what happened to them will be revealed below.

DES LILYA’S AND ARNOLD WEBB’S RECOLLECTIONS OF THE ESCAPE

Two of the men who escaped, Des Lilya and Arnold Webb, have left their recollections of this remarkable adventure. Lilya’s account was first published in the April 1991 issue of the ‘Courier’. [2] David Dexter had asked Lilya to prepare it when they were both serving as members of Z Force in late 1944 or early 1945. Arnold Webb’s account was sympathetically recorded by Paddy Kenneally probably sometime in the early 1990s and has not been published before. [3]

This post includes both men’s stories displayed side by side so that their recollection of particular events can be compared up until the time they parted company during their journey back to Australia.

When it became known by the senior officers of No. 2 Independent Company what the four men had done the initial reaction was that they should all be treated as deserters when they made it back to Australia. Webb and Larney were taken into custody and treated very harshly. Freeman and Lilya who had made it home separately and had demonstrated their soldierly qualities along the way were not incarcerated. All four avoided court martial by agreeing to return to Timor with the No. 4 Independent Company on the ill-fated ‘Voyager’ in August 1942 and served out the remainder of the campaign with the No. 2 Independent Company.

It is apparent from what follows that no long term ‘hard feelings’ were harboured against the four men who were well-regarded by their fellow soldiers, both officers and other ranks.

INTRODUCTION BY PADDY KENNEALLY

This is an account given to me by Arnold Webb [4] of the journey undertaken by himself and Bob Larney [5] when they left the 2/2nd Independent Company, with the object of reaching Australia and reporting the 2/2nd still operating as a force in the mountains of Timor. It is important that conditions in Timor at this time be known and appreciated, to understand why these two men would leave their unit to attempt such a hazardous undertaking. [6]

Briefly, the 2/2nd Independent Company had been sent into neutral Portuguese Timor in December 1941 to forestall an intended Japanese base being formed there in the guise of establishing a civil aerodrome at Dili. This company was to be withdrawn to Dutch Timor when Portuguese troops from Mozambique arrived to reinforce the small garrison of Portuguese troops already in Timor. Nothing went according to plan. The Japanese advance down through Malaya and the subsequent surrender of Singapore and the speed with which they accomplished the conquest of all the East Indies, changed all previous plans for the 2/2nd in Timor. The Portuguese prudently turned back. The Japanese quickly arrived on 19th February 1942. A section of 2/2nd men held the air strip through the night. At dawn they blew up the runway and made their escape out of Dili. The Dutch and their H.Q. had already left.

The main body of the 2/2nd dispersed in the mountains, did not even know the Japanese had landed until late next morning.

Then the fun and games began. Rumours, rumours and more rumours, men being sent everywhere on patrols and coming back with more rumours, ammunition being moved to various dumps, other stores such as food was no worry - we didn't have any. The Company had landed with one month's supply of rations. There were Dutchmen and Javanese wandering everywhere, mainly west for Dutch Timor until they found out that was gone too. Stragglers coming through from Dutch Timor, were bringing further rumours and little else. The 2/2nd H.Q. was desperately trying to establish the true position. 2i/c, Captain Callinan, was on the go day and night all the way down into Dutch Timor attempting to get a true picture of the position and trying to sift fact from fiction. It is easy to follow the ordinary Private's reaction; in Army parlance, 'Who's up who and who is paying?'

With this background, many of the men were doing a bit of planning on their own.

(Sgd) PADDY KENNEALLY

DES LILYA’S STORY

ARNOLD WEBB’S STORY

Reinforcement

On January 16th, 1941, I sailed from Darwin as a reinforcement to the 2/2 Independent Company which was stationed somewhere in the NEI [Netherlands East Indies]. After three days at sea, we arrived at Koepang, the capital of Dutch Timor. Our party for the 2/2 AIC [Australian Independent Company] consisted of 50 ORs [Other Ranks] and 3 officers. We were immediately transferred to a Dutch gunboat, and after half a day wandering through the dusty, yet somehow picturesque street of the small capital, we sailed for Dili the capital of Portuguese Timor.

Three Spurs – Railaco – Vila Maria

On arriving the following day, we moved straight out to the Dili drome and I was taken on by truck to Three Spurs camp. There we were made into "D" platoon, and after about a week we moved on to occupy Railaco. Here we stayed about 3 weeks digging AA [Anti-Aircraft] defences and building Water Pipe Camp. Then a subsection of us with Mr Laffy in charge, moved on to make the first ·staging camp at Villa Maria.

Here, our fine leader became deeply infatuated with a Portuguese by the name of Brendalina de Silva. [7] But on the night of February 19-20th, news came through that the Japs had landed at Dili in force, and our movements were much faster from then on. Major Spence came through and detailed us all our jobs and patrols.

‘The subject came up about the possibility of making an attempt to reach Australia …’

We left Railaco with Company H.Q. Some days after the Japanese landing in Dili, we crossed the Glano River and headed for Vila Maria. H.Q. was established here. Patrols were coming and going, and ammunition dumps were being established over a wide area of mountains. The wet season was in. Up in the mountains we were shivering from cold or malaria or both. Food was extremely short. At this time, I, with some other men including Bob Larney were assigned to H.Q. We knew little of what the position was. All kinds of stories were circulating as to what was happening elsewhere as we were constantly patrolling. We certainly knew the position in our own area. We talked about prospects amongst ourselves. We knew we had no contact with Australia and were cut off. Any news we gleaned came from the Portuguese who had wireless receiving sets, or just plain rumours.

The subject came up about the possibility of making an attempt to reach Australia. Bob Larney was all for it as were some of the H.Q. originals, but no one wanted to be the one to attempt it. Bob Larney was willing but finding a partner to 'give it a go' was a different matter. Bob finally convinced me it was worth a try. We left that night. Some, if not all of those H.Q. men, knew we were going. However, little did we know what we were letting ourselves in for over the next three months. It would have been at the end of February or very early in March when we left the Company somewhere in-the Ermera, Vila Maria area.

West to Memo

Once again with Laffy in command we set out but this time we kept to the hills and after two days hard going we came to Atsabe. Here we procured horses and moved to Bobonaro and were given excellent treatment by the Controller, Sousa Santos and his pretty wife. Here Mr Laffy told us of his plan of going to Suai and procuring a boat and heading for Australia. But he changed his mind and we left for Memo and on arriving at Memo he said that he was not going on with it.