-

Posts

619 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Edward Willis's Achievements

-

Dear Afonso: Many thanks for your kind response to my story about your great grandfather Dom Aleixo Corte-Real - it is an amazing story of courageous resistance and leadership and deserves to be much better known both in Australia and Timor-Leste!! You mention you commute between Dili and Australia - where do you visit when in Australia? I would appreciate meeting with you when you are next in Australia. I live in Mandurah, south of Perth in Western Australia. Kind regards Ed Willis

-

Edward Willis started following Charles Rodger DUNKLEY and Frederick William GROWNS

-

-

CAPTAIN ROGER ‘DOC’ DUNKLEY, THE 2/2’s LEGENDARY MEDICAL OFFICER DURING THE TIMOR CAMPAIGN Captain Roger ‘Doc’ Dunkley – probably at the Tidal River training camp 1941 [1] Back in 2001 Jack Carey wrote in the ‘Courier’: ‘On the eve of the 60th anniversary of the formation of the unit in July 1941, we thought it would be fitting to pay a small tribute to our first Medical Officer Captain Rodger ‘Doc’ Dunkley. His youngest son Stuart (Pip) Dunkley has kindly provided the following short biography on his father’. [2] CHARLES RODGER DUNKLEY 1899-1969 Charles Rodger Dunkley (hereafter called Rodger) was born in South Melbourne 5 October 1899, the son of Charles Alfred Dunkley and Jane Rodger Dunkley. At an early age his father, who was a ships officer, was drowned whilst attempting to save a swimmer in difficulties at a suburban Melbourne beach. This unfortunate incident left Jane a widow, with 2 children, Rodger and his younger brother Alfred. In search of a more secure future for her children Jane left Rodger and Alfred in the care of her family relations and moved to Western Australia where she gained employment as a nursing assistant in the Goldfields town of Leonora. It was during this time that she met and subsequently married a pharmaceutical chemist by the name of Frank Ernest Gibson, later to become Sir Frank Gibson, Mayor of the City of Fremantle and Member of the West Australian Legislative Council. In about 1911, Jane sent for her children and it was Rodger, aged 11, who responsibly brought Alfred to Kalgoorlie on the Trans-Australia train to be reunited with their mother and to meet their soon to be step-father, Frank Gibson. The journey across the continent was, no doubt, a dark frightening experience for this young boy but he accepted responsibility then as he accepted it for the remainder of his life. The new family located to Fremantle and Rodger was educated at the Perth Modern School. He completed his schooling at the end of the school year of 1915, and it was in 1916 that he volunteered for service with the Australian Imperial Force. After his basic training he was posted to 28th Battalion, a WA unit and saw active service in France. In 1918 Rodger succumbed to the Spanish Flu epidemic and spent almost 12 months recuperating in various Australian general hospitals, including some months in Italy. A legacy of this illness was the weak chest and associated respiratory problems that accompanied him on the remainder of his journey through life. On his return to Australia he was accepted by the University of Melbourne as an Undergraduate in the Faculty of Medicine and for the next 6 years he studied hard. During this time he lived at the University of Melbourne’s “Ormond” College. Upon graduation, Rodger returned to Western Australia and was granted an internship at Fremantle Hospital. It was during this time that he met Jessie Mary Mackay, a resident of Fremantle. They were married in 1928 and settled in Ellen Street Fremantle. They had 2 sons, Ross born in 1931 and Stuart (Pip) in 1934. Rodger conducted a busy practice up to 1940 when he again, answered the call and in due course, became the inaugural Medical Officer of the 2nd Australian Independent Company and accompanied that unit to Timor. Your members will know more of his exploits there than I do; suffice to say that he accepted the responsibility of his commission honourably and with the compassion of his calling. On the units return to Australia, Rodger departed the ranks of 2/2nd and for the remainder of the war years he was engaged in duties pertaining to service with the Royal Australian Medical Corps. This included active service in Borneo, where he was stationed at the time of the Japanese capitulation. After “de-mob” he returned to his Fremantle practice from which he retired in 1964. Until the time of his death Rodger was the District Officer for the Western Australian Police Service and was also Area Medical Officer for the Army. In 1968 he and Jess sold the family home in Fremantle and built a new house in Swanbourne. He was able to continue his passion for gardening and in particular, roses, at this abode until his death on 14 May 1969 aged 69 years. Rodger Dunkley was a humble man. He was a good role model to all; honourable, loyal, sincere and his integrity could not be questioned. He was his own man but fair to all others. He could not tolerate “bludgers” or “free loaders” and, at times, appeared to be intolerant of others. However, if you were “down and out” and it looked like the end of the road, Rodger Dunkley was there for you with a kind word and a helping hand. His compassion was boundless. Pip Dunkley Jack complemented Pip’s biographical note with a following article summarising ‘Doc’ Dunkley’s outstanding contribution during the Timor campaign: [3] “The ‘Doc’ as he was affectionately known, was the unit’s Medical Officer (M.O) from its formation in July 1941 to December 1942. He did an outstanding job throughout the difficult and hazardous Timor campaign in 1942. He soon made it clear to the men to whom he was responsible, that he would stand no nonsense. If a man was genuinely sick the Doc and his orderlies would do all that they could for the soldier, but woe betide anyone who tried to put one over. The ‘Doc’, a World War 1 veteran, would give the malingerer a nice old tongue lashing, and send him on his way. They seldom tried it again. The Doc was really put to the test early in 1942 when 90% of the men went down with malaria in the course of a few weeks. The Doc and his staff worked around the clock in makeshift wards, caring for the men day in and day out until they were back on their feet again. The subsequent decision on his recommendation, to move the men away from the mosquito infested drome area to the nearby mountains, had the effect of getting the troops back in fighting shape. This was to eventually enable the 2/2nd men to carry out a successful campaign against the Japs after they occupied Dili on 20th February 1942. The Doc was forced to make a number of moves so he could carry on his good work, restoring the health of the sick, attending the wounded and those with serious tropical diseases, Railaco, Same and Ainaro were some of these places. Ainaro eventually became his main base. Up until the end of April, medical supplies were limited, but once contact was made with the mainland things began to improve. Pip (son of Dr Roger Dunkley) and Barb Dunkley in front of the current Ainaro Hospital that stands on the site of the old Portuguese era hospital – 27 April 2014 Those survivors of the campaign will remember the great care and attention he gave Alan Hollow, Keith Hayes, Gerry Maley, Eddie Craighill, and others, who were badly wounded and seriously ill. The Doc, who painted his back with iodine and nursed him back to health, saved Colin Doig who was at deaths door when the natives carried him in with double pneumonia. Those with ulcers always grimaced when the Doc used to scrape out the pus and poison with a spoon. Ulcers turn very nasty in the tropics. God knows how many men the Doc and his orderlies treated in those hectic 12 months, but to his credit Rodger Dunkley never wavered, he did a mighty job. Don Turton likes to tell the story that when he and the Doc set out with a small escort to rescue Gerry Maley, who was wounded and was being cared for by the natives in a hut, in a Jap area, they sighted a number of Japs swimming in a pool some distance away, “let’s do them over” said the Doc. Don had to talk him out of his suggestion, saying it could jeopardise the chance of rescuing Gerry. The Doc reluctantly agreed and Gerry was duly rescued. [4] Why Rodger Dunkley’s outstanding contribution on Timor went unrecognised is a sore point with all those who served in that campaign and were aware of the great work he had done there. If ever a man was entitled to a Distinguished Service Order it was he. It was a great injustice. Maybe it was because of the change of command during the campaign, firstly Alec Spence then Bernie Callinan and finally Geoff Laidlaw. It was an oversight on someone’s part that no commendation for a higher award was ever made, apart from a M.I.D. These things happen in the army. Not that it would have upset the Doc, he was not an honour seeking man, and his main concern was always for the men under his care. We could not have had a better man for our M.O. [5] The orderlies, who assisted Rodger during his time with us in Cliff Paff, Alan Luby, Fred Sparkman, Alec Wares, and Boy Coates, also deserve a special mention. Jack Carey REFERENCES [1] https://doublereds.org.au/history/men-of-the-22/wx/charles-rodger-dunkley-r96/ [2] Stuart (Pip) Dunkley ‘Roger Dunkley M.O.’ Courier 137 June 2001: 15-16. https://doublereds.org.au/couriers/2001/Courier%20June%202001.pdf [3] Jack Carey ‘Roger Dunkley M.O.’ Courier 137 June 2001: 16-17. https://doublereds.org.au/couriers/2001/Courier%20June%202001.pdf [4] https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/R1579678 [5] https://museum.wa.gov.au/debt-of-honour/dunkley-s-mobile-hospital ADDITIONAL READING Dunkley Charles Roger : SERN 52043 : POB Port Melbourne VIC : POE Perth WA : NOK M Gibson Jean Roger. - NAA: B2455, DUNKLEY C R. - https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/DetailsReports/ItemDetail.aspx?Barcode=3527236&isAv=N Dunkley Charles Rodger : Service Number - WX11064 : Date of birth - 05 Oct 1899 : Place of birth - MELBOURNE VIC : Place of enlistment - PERTH WA : Next of Kin - DUNKLEY JESSIE. - NAA: B883, WX11064. - https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/DetailsReports/ItemDetail.aspx?Barcode=6455585&isAv=N Hal G.P. Colebatch ‘Dr Roger Dunkley, forgotten hero of World War II’ News Weekly 2945 April 2015 :17-18. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/ielapa.125515824810966 ‘Vale Doctor Roger Dunkley’ Courier 23 (215) June 1969: 3. https://doublereds.org.au/couriers/1969/Courier%20June%201969.pdf

-

Edward Willis started following ‘MERCIFUL JOURNEY’ – LIEUTENANT MARSDEN HORDERN, RAN, FAIRMILE PATROL BOATS ML814 AND 815 AND OPERATION ‘MOSQUITO’ – DARWIN TO THE SOUTH COAST OF PORTUGUESE TIMOR – AUGUST 1-3 1943 , ST ANTHONY'S INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL - SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM , “FEW SOLDIERS IN HISTORY CAN CLAIM TO HAVE DONE MORE THAN THAT” – THE STORY OF NEVIL SHUTE’S “INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER” TO BERNARD CALLINAN’S “INDEPENDENT COMPANY” and 1 other

-

Dear Mr Wills, We hope this email finds you and your family well. On behalf of students, parents and our staff of St Anthony's International School ( SAIS), I would like to once again express your profound gratitude and appreciation to the outstanding support and assistance from the 2/2 Commando Association of Australia to our school and the people of Timor-Leste. I would also like to take this opportunity to kindly propose the 2/2 Commando if it would be possible to offer a scholarship program to our unprivileged students for next year? Some of our students' parents are having a very difficult time paying the school fee even though the school has been trying its best to help them by giving them a significant discount and the school itself is offering a coulpe of scholarships to unprivileged students since the school was estabilished in 2017. If there is a possibility of offering the scholarship by the 2/2 Commando, we will very please to name the scholarship" the 2/2 Commando Scholarship Program" or there might be another name that 2/2 Commando preferes. Below is the school annualy fee for the year of 2025: Year 1 - Yerar 3 US$ 2545 Year 4 - Year 5 US$ 2880 Year 6 US$ 3200 Year 7 - Year 8 US$ 3270 Year 9 US$ 3280 There is a coulpe of unprivileged students' parrents have been desperately paying the school fee for their kids to access a good quality of education. Thus, the scholarship program from the 2/2 Commando would be extremely helpfull for the parrents and students to prusue their dreams. Thank you. Best regards, Cesar Dias Quintas and Cristina Yuri Rebello Santos Costa

-

The best-selling novelist Nevil Shute (1899-1960) wrote the following paragraphs to open and conclude his introductory chapter to Bernard Callinan’s classic personal memoir “Independent Company” that was first published in 1953. [1] Couched in Shute’s consistently economical and easy to read language these paragraphs provide a valuable and unique concise assessment of the commando campaign on Timor. “Of all the many campaigns which in their total constituted the Second World War the little campaign of the Australian Commandos in Portuguese Timor is perhaps the least known and one of the most worthy of notice. ….. They were one of three small forces which between them immobilized two Japanese divisions. At sea, the American submarines were operating from Fremantle against Japanese shipping with increasing success, and in the air the squadrons of the American and Australian Air Forces were operating from airfields in the Northern Territory with increasing strength. These activities, with those of the Australian Commandos in Timor, convinced the Japanese High Command that a counter offensive from Australia was in preparation. Accordingly they sent their 48th Division to Timor to reinforce the existing garrison; this was an experienced division of fifteen thousand men which had served in China, the Philippines, and Java. The same anxiety later caused them to send their 5th Division, which had fought in Malaya, to the Ambon and western New Guinea area, and to form from these divisions a new army with headquarters on Ceram Island. These three small, valiant efforts on the land, the sea, and in the air, immobilized over thirty thousand Japanese troops, at what was possibly the worst time in the war for the Allies. Few soldiers in history can claim to have done more than that”. In an earlier post on Doublereds where Bernard Callinan explained ‘Why I wrote “Independent Company”’ readers may recall the distinctive book cover, characteristic of the era when the book was published (1953), that incorporated the statement in bold letters ‘INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER by Nevil Shute’. [2] Front cover of “Independent Company” with Shute’s contribution highlighted Nevil Shute (1899 - 1960) was the pen name of Nevil Shute Norway, popular novelist, born in England, who later (1950) settled in Australia. His many readable, fast‐moving novels, several based on his involvement with the aircraft industry and his own wartime experiences, include Pied Piper (1942); No Highway (1948); A Town Like Alice (1950), in which an English girl is captured by the Japanese and survives the war to settle in Australia; and On the Beach (1957), which describes events in Melbourne after a nuclear holocaust. [3] Shute’s most recent biographer provides the background to how he came to assist Callinan with the book: “With ‘The Far Country’ now published, the manuscript of ‘In the Wet’ with the publishers, and no new novel yet underway, Norway occupied himself towards the end of the year by working on a chapter for a military history book. Lieutenant Colonel Bernard Callinan, who was living just along the coast at Beaumaris, had written a book on the activities of the 2/2 and 2/4 Australian Independent Companies in Portuguese Timor during the Second World War. As someone with no literary contacts, or previous experience as an author, Callinan contacted Norway for help in getting this book published. Given the letter Norway had written to the Society of Authors the previous year about the urgent need to support local Australian authors, not surprisingly he was generous in his support. In the end he not only wrote a detailed introductory chapter, but supplied his secretary to type the first draft, and no doubt he used his considerable influence with the local Heinemann office in getting the book published”. [4] Front cover of biography “Shute: the engineer who became a prince of story tellers” by John Anderson Shute had some familiarity with Timor and its WWII history having transited through Koepang in late November 1948 in company with fellow author James Riddell as a stopover in their epic single-engine light plane flight from England to Australia. “On 22 November they said goodbye to Bali and flew on eastward once more, this time carrying a jerry can of petrol, being unsure of what fuel might be available on the next leg. On landing at Soemba Basar they found the airport organisation in chaos and again their arrival was unexpected. However the Army did produce some petrol to refuel them and accepted a signature against the Shell carnet in return. After 2 hours they took off again for Koepang in East Timor, landing there in a cross wind after a two hour flight. Shute described Koepang as a "bloody place", all the buildings being old Japanese barracks with no proper sanitation or decent accommodation. This did not give the rest required to tackle the next leg of the journey-the crossing of the Timor Sea to Australia. This was a stage of the journey that probably most concerned Shute, a flight of over 400 miles across the open sea. This was by far the longest crossing of open water in the whole trip”. [5] Front cover of Shute biography “Parallel motion” by John Anderson They stopped in Dili on their return journey in late January 1949 – memories of the war and physical evidence of its destructive outcomes were still fresh in both towns at that time. “The following day, 26 January, they arrived back at Darwin, completing their tour of Australia which had lasted 63 days. They wanted to fly from Darwin to Dilly on East Timor, a flight of some 450 miles, 400 of them over the sea. There was a Catalina aircraft scheduled to make the crossing and they arranged to fly in company with that. So on 29 January they cleared Customs for the last time in Australia. The Australian Customs had been the outstanding unpleasant feature of this journey and, Shute noted, made it difficult and unpleasant to fly a British aircraft to Australia. They took off according to plan at 9:35 ahead of the Catalina and flew on course at 900 feet over sea through heavy monsoon rain storms. After Bathurst Island the weather improved and later cleared entirely, so that they could get up to 4000 feet. Wireless contact with the Catalina behind them was good from the start, they came in punctually every quarter of an hour, and this contact was a great comfort on the crossing of the Timor Sea. The Catalina caught up with them off East Timor and said goodbye. From there they flew along the north coast and landed at Dilly, where they were met by the Australian consul who put them up in his house. They stayed at Dilly for some days, being entertained by the Australian consul and his wife and also by the Portuguese Administrator, Senor Mendonca. They were taken by car over a hilly road to Maubisse, which Shute thought a real Shangri-La. On the way back they had to cross a ford which had been small on the way up but was 4 feet deep on the way back. They tried towing the car across but it got stuck and the passengers had to take off their clothes and wade across. Shute's comment was that this was a type of motoring that you didn't see in England: it was great fun, but rough on the cars. They were told that they must fly to Koepang to clear Customs for the Dutch East Indies, but Shute, mindful of his bad experience at Koepang on the outward flight, decided that he would fly on to Bali by way Soembawa Besar to refuel, reckoning that the East Indies were in such chaos that probably no Customs officer would even know that they had landed at Soembawa Besar”. [6] Shute shared the adventures just described with and made a friend of the Australian Consul Doug White who was a public servant of twelve years standing when he took up the position of consul in Dili on 18 October 1947. During the war, he had been an RAAF Squadron Leader and had served in the UK and the Pacific. [7] It’s apparent Shute’s positive travel experience in Timor made him receptive to Callinan’s request to assist with the preparation and publication of his book. White returned to Canberra after completing his term as Consul in Dili at the end of June 1950. Shute wrote to him in early January 1953 with a number of questions regarding the Japanese invasion and occupation of Timor that White referred to Gavin Long, the editor of the official history of Australia in WWII. Subsequently Shute corresponded directly with Long who reviewed the draft of the “Introductory chapter” and they met over lunch at the Cathedral Hotel in Melbourne on 13 February 1953. [8] Front cover of Gavin Long biography “Great at heart” by Garry Hills [9] Shute also consulted with Lieutenant General Sir Vernon Sturdee, former Chief of the General Staff, regarding strategy and the formation and training of the independent companies and Lieutenant Colonel William Leggatt in relation to the deployment of Sparrow Force and its defence of Dutch Timor against the invading Japanese – Sturdee also contributed a foreword to the book. [10] Callinan and Shute lived in close proximity to each other (36 kilometres apart) in the bayside southeast suburbs of Melbourne (Beaumaris [11] and Langwarrin South [12]), corresponded and met on occasion. Callinan loaned Shute his copy of the “Area study of Portuguese Timor” [13] and it is apparent from his introductory chapter that he had carefully read and digested the content of the manuscript of “Independent Company”. Recall that, when published later in 1953, it was the first monograph to provide substantial coverage of the Timor campaign. [14] Since then, Shute’s contribution to the history of the campaign has been recognised by later historians including Steve Farram [15] who observed: “Nevil Shute, in his introduction to Callinan’s book, repeats some of the commonplace allegations of ‘disloyalty’ on the part of the West Timorese, but makes also a number of interesting observations. The West Timorese and the East Timorese, he says, had no particular reason to be ‘loyal’ to the Dutch or the Portuguese anyway; ‘a conquest by the Japanese meant merely the exchange of one master for another’. This is a very important point. The Dutch had brought a halt to the endless cycle of warfare in West Timor and introduced schools and medical, agricultural and other services which were recognised by some West Timorese as being of benefit to their people. Many others, however, saw it as merely interference in their way of life. The Dutch, therefore, are just as likely to have engendered resentment as ‘loyalty’. The notion of ‘loyalty’, moreover, was something which most West Timorese at the time would have applied at a much more local level by being ‘loyal’ to their raja or their suku (clan). While certain individuals may have been ‘loyal’ to the Dutch or Portuguese there were districts, such as Belu in West Timor and Maubisse in Portuguese Timor, which had a long history of opposition to colonial rule. That people from those districts should have turned against the Europeans is not surprising, but this does not mean they were ‘pro-Japanese’. Shute goes on to argue that the swift defeat of the Dutch and their allies in West Timor meant it was obvious that the Japanese were the new masters and the West Timorese felt no obligation to help the defeated party. It has been shown above that many West Timorese did continue to give the Allied troops support after their surrender, but Shute’s point is still valid as many West Timorese may have felt obliged to help the Japanese as they were clearly in control and soon made it known that they would deal harshly with whoever disobeyed them. Shute argues that the situation was different in Portuguese Timor because the Australians of the 2/2 Independent Company, trained in guerilla tactics, had resounding success against the Japanese and killed nearly forty of them for every loss on their own side. This impressed the East Timorese who were then most willing to offer their assistance. As the Japanese increased their offensive against the Australians and the Australians’ effectiveness declined, so did the support they received from the local people. In a fitting conclusion to this post, more recently Heather Merle Benbow noted [16]: “[In] an early memoir of the battle, published in 1953 by the second in command of the 2/2nd Independent Company, Bernard Callinan (1913–1995) - later the commander of Sparrow Force - describes the daily encounters around and struggles for food. In the introduction to Callinan’s “Independent Company: the Australian Army in Portuguese Timor 1941–43”, Nevil Shute emphasises the crucial role played by food in the conflict: “Colonel Callinan formed the opinion that two factors are necessary for success in guerrilla operations: a friendly population and a surplus of food in the country over and above the needs of the population. Without the latter, friendly relations with the population can hardly be established, and without friendly relations a guerrilla campaign can hardly succeed. The first requirement of all, therefore, seems to be the food supply”. ….. “It is no coincidence that, as hunger takes hold on the island, many more Timorese collaborate with the IJA. It is common to attribute these developments to the food situation (Shute 1984: xxvii), but as the war diaries make clear, other factors including anti-colonial sentiment play a part. It is clear, though, that food is the substance that bonds the Australians with the Timorese. The relationships the Australian soldiers form with these men and boys, as well as many acts of hospitality by Timorese locals, underpin the strong feelings of gratitude and indebtedness that dominate in the memory of Timor within the Australian military”. REFERENCES [1] Bernard Callinan. - Independent company: the 2/2 and 2/4 Australian Independent Companies in Portuguese Timor, 1941-1943. “Introductory chapter” by Nevil Shute. - Melbourne: Heinemann, 1953 (repr. 1989): xvii- xxxiii. [2] https://doublereds.org.au/forums/topic/286-why-i-wrote-‘independent-company’-bernard-callinan/#comment-661 [3] See “Nevil Shute” in The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature (2 ed.) / William H. Wilde, Joy Hooton, and Barry Andrews. Publisher: Oxford University Press Print Publication Date: 1994 Print ISBN-13: 9780195533811 Published online: 2005 Current Online Version: 2005 e ISBN: 978019173. Accessed 1 April 2025 [4] Richard Thorn. – Shute: the engineer who became a prince of storytellers. - Kibworth Beauchamp, Leicestershire: Troubadour Publishing, 2017: 196. [5] John Anderson. - Parallel motion: a biography of Nevil Shute Norway. - Kerhonkson, N.Y.: Paper Tiger, c2011: 189. [6] Anderson, Parallel motion: 203-4. [7] Steven Farram. - A short-lived enthusiasm: the Australian Consulate in Portuguese Timor. - Darwin, N.T.: Charles Darwin University Press, 2010: 47. [8] Copies of letters held in the 2/2 Commando Association of Australia archives. [9] Garry Hills. - Great at heart: Gavin Merrick Long Australia’s official Second World War historian. – Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2025. [10] Callinan, Independent company, “Foreword” by Lieutenant General Sir Vernon Sturdee: xiii-xv. [11] It is interesting to note Callinan named his Beaumaris house “Lete Foho” in fond memory of his favourite posto in Portuguese Timor; see “Lete-Foho (Nova Obidos)” in Edward Willis. – WWII in East Timor: an Australian Army site and travel guide. – Perth: 2/2 Commando Association of Australia, 2024: 344-350. [12] Samantha Landy “Author Nevil Shute’s former home and Hollywood celebrity haunt a bestseller in Langwarrin South” https://www.realestate.com.au/news/author-nevil-shutes-former-home-and-hollywood-celebrity-haunt-a-bestseller-in-langwarrin-south/ . Accessed 1 April 2025. [13] Area study of Portuguese Timor / Allied Geographical Section, South West Pacific Area. - [Brisbane] : The Section, 1943. – (Terrain study (Allied Forces. South West Pacific Area. Allied Geographical Section) ; no. 50.) https://repository.monash.edu/items/show/26455#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0 . Accessed 1 April 2025. [14] The relevant chapters of the Australian official history weren’t published until 1957 and 1959; see Lionel Wigmore, Ch. 21 “Resistance in Timor” in The Japanese thrust. - Canberra : Australian War Memorial, 1957. (Australia in the war of 1939-1945. Series 1, Army ; v. 4): 466-495 and Dudley McCarthy, Appendix 2 “Timor” in South-west Pacific area - first year : Kokoda to Wau. - Canberra : Australian War Memorial, 1959. (Australia in the war of 1939-1945. Series 1, Army ; v. 5): 598-624. [15] Steven Glen Farram. - From ‘Timor Koepang’ To ‘Timor NTT’: a political history of West Timor, 1901-1967. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. – Darwin: Charles Darwin University, 2004: 187-188 [16] Heather Merle Benbow (2018) “Commensality and conflict: food, drink and intercultural encounters in the Battle of Timor” Journal of Intercultural Studies 39 (1): 35-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2017.1410113 . Accessed 1 April 2025.

-

INTRODUCTION Colin Douglas (Col) Doig OAM - WX11054 - was an original member of the No. 2 Australian Independent Company and served with the unit throughout WWII. [1] After the war he was the instigator for the establishment of the 2/2 Commando Association and its mainstay for the remainder of his life, including founding and long term editor of the Courier. After Col’s passing in 1996, his compatriot Don Turton prepared a heartfelt and well-informed tribute to his close friend that he delivered at his funeral and is the focus of this post. Understandably for the occasion, Turton only made a brief reference to Doig’s wartime service including his near death experience from Black Water Fever on Timor and being nursed back to reasonable health under the care of Dr Roger Dunkley. However, Doig’s frontline presence in all the unit’s campaigns put him and the soldiers under his command at great risk of survival; at least two such occasions have been covered in previous Doublereds posts and relate to the daring rescue of downed Hudson pilot Flying Officer Sid Wadey from Baguia, Portuguese Timor [2] in August 1942 and his leadership during a firefight with the Japanese at Orguruna, Ramu Valley, New Guinea in October 1943. [3] Don Turton’s tribute to Col Doig follows. Photo from Col Doig’s service record A TRIBUTE TO COLIN [4] I can visualise Colin fronting up to St. Peter at the Pearly Gates and St. Peter saying to Col "I don't see your name on the list of the faithful Mr Doig" and Colin replying, "Now hang on a minute Pete, I was a contributor down below". And then he proceeds to tell St. Peter one of his very, very old stories, the one about Dad and Dave and the visiting parson. When the parson man is taken aback by the carryings on at the Rudd family tea table and raises his eyes to the ceiling and says, "Let there be light on this darkened house," dad says to Dave "You'd better hop up on the roof Dave and knock a few shingles off, this old so and so is going blind!" With that St. Peter throws back his head and laughs saying, "You'd better come on in, this place could do with a bit of brightening up". I'm sure that is how many of us gathered here this morning would like to remember Colin as a good friend and a great storyteller who helped brighten up our lives. Front cover of Col Doig’s personal memoir The ramblings of a ratbag The Doig clan of which Colin was a member is of Scottish ancestry. In 1897 Alexander and Maria Doig with four children left Beltana in South Australia and took up a holding in Wagin, in the Great Southern district. Four more children followed of whom Colin Douglas Doig was the last born on 3rd March, 1912. ''The scrapings of the pot" was how Colin later referred to his birth. He had a happy childhood although he had the misfortune to lose his father who died as the result of an accident in 1920 when Colin was only 8 years old. His mother Maria was a strong and very active woman. Not only did she raise a large family she was also a midwife, was called upon to lay out the dead for burial and involved herself in many other community affairs. She was also an active campaigner for the Liberal Party. She lived to 89 and was truly a remarkable lady. Colin loved his sport and was a handy cricketer and a good runner. He unfortunately developed some bad habits. He learned to swear profusely at an early age and took up smoking when quite young. He tells the story in his autobiography how on one occasion the school headmaster gave him a shilling and sent him down to the local store to buy a packet of cigarettes which he did. He promptly opened the packet and smoked one on the way back for which he copped six of the best. The headmaster was Oscar Charlesworth, grandfather of Ric Charlesworth of cricket and hockey fame. Despite receiving many canings in the course of his school life, Colin was a bright lad and finished up dux of his small school. He was also taught to box by a Mr McDonald and as a result became very handy with his "Dooks". He also learned the rougher side of brawling and knew how to look after himself. He was very proud of his eldest brother Peter who was 25 years older. Peter served in Palestine in the 10th Light Horse and won a Military Cross for bravery at Jenin in 1918. One of his most vivid recollections of his childhood was when he was six years old and peace was declared on 11th November, 1918. He could well recall the church bells ringing and everyone turning out in the town to celebrate the occasion. He was a callow youth of 17 when the Wall Street Crash of 1929 heralded the start of the Great Depression which swept the world. For the next 12 years until he entered the 2nd A.I.F. in 1941, Colin tried his hand at many things. He certainly crammed a lot into those 12 years and fortunately for posterity he has duly recorded his experiences in his book The Ramblings of a Ratbag [5] of which many of us have a copy. He was at some stage or other a horse breaker, cattle musterer, a shearer, had a camel team on the rabbit proof fence, was in a boxing troupe, worked for many a cocky, rode in rodeos, had contracts sinking dams and so on. He also returned from time to time to help out on the family farm. These were tough times and people needed to be equally tough to survive. Throughout these experiences Colin always retained his keen sense of humour and could always relate to the very many humorous incidents he was involved in. His description of the time spent with the camel team is hilarious. He complained that camels seem to be able to kick with all four feet at once and the smell of their breath was really damnable. He got camel sick many a time with their "Bloody rolling gait" and lost many a breakfast as a result. During these years his language got worse and he could put a bullocky to shame. He became like The Man From Snowy River hard, tough and wiry and drank and smoked a lot - all bad habits. He was blessed with a wonderful retentive memory and never forgot the many odd and humorous characters he met in his travels. He always had a close interest in people and developed a compassion for the battlers of his time. In the late 30s he joined the 25th Light Horse Regiment and received a commission and when war broke out after several attempts to transfer to the A.I.F. were knocked back he finally succeeded. A short time after he joined the Hush Hush crowd at Northam and finished up after training in Wilson's Promontory. An original member of the No. 2 Australian Independent Company, later known as the 2/2nd Commando Squadron, he served as an officer in the Unit's Timor, New Guinea and New Britain campaigns and was made a captain in 1945. Early in the Timor campaign he contracted pleurisy and Black Water Fever and nearly died. He was in Bobonaro at the time and the trip from there to Ainaro where Doc. Dunkley nursed him back to health, took over three days. He was forever grateful to the Timorese for carrying him on this journey and never forgot the debt he owed them for saving his life. Colin, a capable officer, was well respected and liked by his men. He had a wealth of good yarns to tell and always enjoyed a beer or two. Front cover of Col Doig’s unit history He was a real down to earth character and a soft touch. He loaned many a quid most of which he never got back. He was more at home in the company of men and it came as a bit of a surprise when word came through that he had married a Julia Pemberton in January 1946. Following his discharge Colin and his bride returned to Perth and for a few years they were domiciled in the old Ozone Hotel near the causeway. He obtained a job with the Department of Labour and National Service where the late Tom Murray, Don's father was his boss. He enjoyed his work in the Department and was a competent officer. To earn a bit of spare money he also got a job as clerk for Bill Maloney, a trot bookie and a former top East Perth footballer. He added many racing stories to his collection during his working life with old Bill. In 1952 he and Julia moved to their new home at 77 Rosedale Street, Floreat Park where he was to spend his next 44 years. This was the beginning of the second phase of his life. Before leaving New Britain he chaired a meeting of Unit members prior to it being disbanded. It was unanimously agreed that we should carry on our wartime friendships in the form of an Association to be known as the 2/2nd Commando Association of Australia. From that time onwards until he breathed his last Colin was a tireless worker for the Association. He was our first general secretary and editor, a job he undertook for over 23 years. He was made our first Life Member in 1950 and was president in 1953 and 54. He was involved in practically every important activity in which the West Australian Branch undertook and these were many. His contribution to our little paper, the Courier, was unsurpassed. The greatest tribute we can pay him is to simply say "Things won't be the same without him". Col Doig’s certificate for the Order of Australia In 1958 Colin was transferred to the Department of Social Service where he remained until his retirement in 1976. For relaxation he liked his weekend sport and was a regular patron of the local football of a Saturday. He was a West Perth supporter and became quite vocal on the odd occasion. He liked to have a drink and yarn with his old mates at the Royal, Globe and old Imperial. Colin was not an ambitious man. He liked nothing better than to sit around a table with a glass of beer and his friends and talk sport, politics or any other subject or relate humorous experiences from his years of knocking around the bush. He was a most interesting man and one felt all the better for having been in his company. He also got a lot of pleasure from his garden and vegie plot. He was proud of his sweet peas, poppies and kangaroo paws. He was forever giving away flowers and vegies to his many friends - such was his generous nature. He underwent a number of crises in his life. The first and most serious was the breakdown of his marriage. This really knocked him and he sought sanctuary in drink which seriously affected his health and lifestyle. The advent of Joy Lowden as housekeeper steadied the ship and things started to return to normal although he still continued to drink too much. He was also smoking a lot, eventually things caught up with him. I remember going around to see him one morning and was dismayed to see his poor physical state and I said to him "You'd better see a doctor immediately", which he did. He finished up in hospital and for a time was on the seriously ill list and did not look like coming through his crises. His toughness prevailed and he made it. Following this his doctor read him the riot act of which he took heed and from that time onward his health improved and he started to look after himself. Even after the death of Joy, which he felt very keenly, he continued to do the right thing by himself. Cover of Col Doig’s history of the 2/2 Commando Association Some highlights of his life of which he was quietly proud, was when he and Ron Kirkwood met Prime Minister, John Gorton, in 1968 and succeeded in obtaining a grant for the erection of the Dare Memorial in East Timor. He also played a major part in organising arrangements for our trip to Timor in April 1969 for the opening of the Memorial which went off very well. The other highlight was his Australian honours award of his O.A.M. in June 1988. He was in hospital at the time and it gave him a great lift. Colin was a well-read man particularly in his retirement years. He was a regular at the local library and enjoyed all types of books. He could write well and if things had been different could have been a top journalist. He had a sharp intellect and a man of great perspicacity. He was indeed gifted. In spite of a nagging leg ulcer and failing eyesight the last 12 years or so of his life were in many respects his most rewarding years. He compiled A History of the 2nd Independent Company and 2/2nd Commando Squadron [6], the profits of which he generously gave to the Association. He also wrote The Great Fraternity [7] a detailed history of the Association from 1946-1992, and his own autobiography of the first 34 years of his life under the title of The Ramblings of a Ratbag a book full of humour and interest. He became a great supporter of the Trust Fund to which he gave generously. He also struck up a close relationship with Brother Ephram Santos of the Salesian Order and was very good to him, paying for the good brothers trip to Australia in 1995. One of his last generous gestures was to contribute $10,000 to the Oan Kiak Foundation, the interest on which will be handled by the Don Bosco Training Centre who in turn will see that the Memorial at Fatunaba is maintained in a sound condition. He was indeed a generous man and helped other causes and people in his later years. For a man who had not religious convictions he was blessed with those two great god given gifts of charity and compassion. He was a charitable man in every sense and his gift of compassion stemmed from those early times in his life when he saw life raw and came to understand the need of the less fortunate. Looking back on his life his 84 years saw him live through a greater part of the 20th century which surely must rank as one of the most exciting and progressive centuries of all time. Colin often spoke of this in his more pensive moods. All this came to an end at 5.40pm last Sunday as a result of a nasty fall he sustained on Friday. It is a sobering thought that before the day is out his worn out frame will become a handful of ashes and having known Colin pretty well for the past 55 years I think he main wish would be that he would like to be remembered for a while. We come and we go in this world and are quickly forgotten and I guess this is the way it has to be. But I know while those of us who are assembled here this morning - Gwen, Robyn and the other direct descendants of Alexander and Maria Doig, his near neighbours, old Waginites, his old mates from the Department of National Service and the members, wives, widows and friends of his beloved 2/2nd Commando Association - while we are still around Colin Doig will not be forgotten. I would like to think that in times ahead whenever any of us are gathered together and the name Colin Doig is mentioned it won't· be long before the conversation begins to quicken and the grins start to appear and the grins turn to laughter as we recall the happy and humorous times spent with this unique Australian character. We loved him and he's gone! The above tribute to Colin was delivered by Mr Don Turton at Colin's funeral service held in the Norfolk Chapel at Karrakatta on Thursday morning, 24th October [1996]. REFERENCES [1] ‘Colin Douglas Doig’ https://doublereds.org.au/history/men-of-the-22/wx/colin-douglas-doig-r94/; ‘Doig, Colin Douglas: Service Number - WX11054 : Date of birth - 03 Mar 1912 : Place of birth - WAGIN WA: Place of enlistment - PERTH WA’ NAA: B883, WX11054https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/DetailsReports/ItemDetail.aspx?Barcode=6469063&isAv=N [2] The Sid Wadey Story – Rescued On Timor - https://shorturl.at/omS3H [3] Fire Fight At Orguruna – The 2/2's Different War In New Guinea - https://shorturl.at/o2G2H [4] Don Turton ‘A tribute to Colin’ 2/2 Commando Courier December 1996: 4-6. [5] C.D. [Col] Doig. - The ramblings of a ratbag. – [Perth, W.A.]: The Author, 1989. [6] C.D. [Col] Doig. - A history of the 2nd Independent Company and 2/2 Commando Squadron. - Carlisle, W.A. : Hesperian Press, 2009. [First published: 1986] [7] C.D. [Col] Doig. - A great fraternity: the story of [the] 2/2nd Commando Association, 1946-1992 / compiled by C.D. Doig. - [Perth, W.A.: C.D. Doig], 1993.

-

Water Treatment Plant -Los Palos Timor Leste

Edward Willis replied to Thomas Hoyer's topic in Funding Proposals

Update from Max Bird (Kwinana Rotary) - "Rotary Projects Timor-Leste East - June 2025 Work Program" 20-1-2025 Project Scope Draft rev 2.docx -

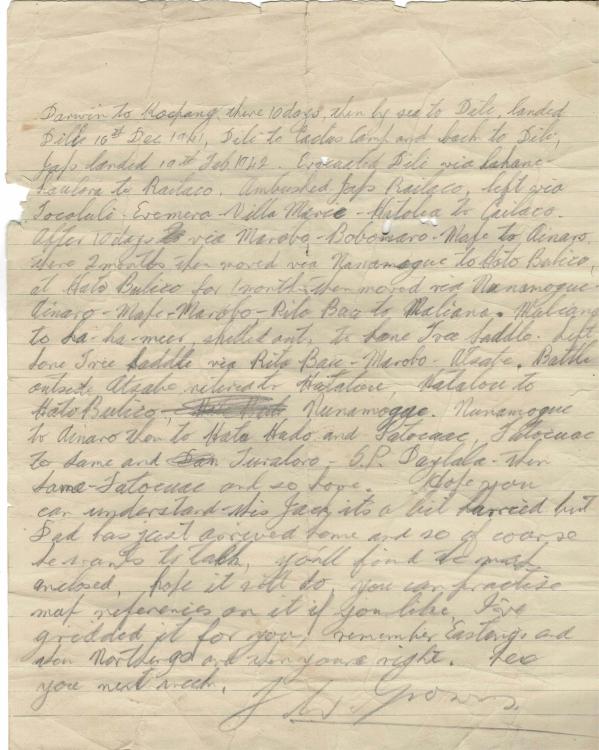

On the occasion of the 83rd anniversary of the Japanese invasion of Portuguese Timor on February 19-20, it is timely to recognise and acknowledge the service of Marsden Hordern - a surviving Australian veteran (almost certainly the last) of the Timor campaign. He is 102 years of age in “reasonable health” and lives in the northern suburbs of Sydney. All Doublereds members and supporters will wish him well. As a 20 year old Navy Lieutenant he was a junior officer on the Royal Australian Navy Fairmile patrol boat ML814 that, accompanied by sister vessel ML814, completed the hazardous Operation Mosquito (August 2-5 1943) involving the insertion, near the mouth of the Dilor River, of SRD (Z Special) signaller Sergeant Jim Ellwood to join Operation Lagarto, the offloading of currency (silver coins), food, medical supplies, weapons and ammunition and the ‘merciful journey’ - evacuation of 87 Portuguese men, women and children back to Darwin (subsequently accommodated at Bob’s Farm Cadre Camp, the topic of another recent post). An interesting aspect of the mission was that an NT Force Intelligence Officer gave Marsden a fake Japanese naval ensign to hoist as a ruse de guerre. He recalled: “I was suspicious, even though sailing under false colours sounded better in French. He did not ask me to sign for the flag and I passed it on to Chips, who was talking signals with D'Arcy on the bridge. They didn't like the sound of it either, and we decided that if we were to be caught, it would be under the White Ensign and not the Rising Sun, reasoning that the Japs had not signed the Geneva Convention and that if they caught us like that they might use blunt swords. As there was no need to worry Reg with such trivia, Chips told D'Arcy not to put it with the 'decent' flags but to 'shove it in the potato locker”. The ensign survived the war and in 1994 was donated to the Australian War Memorial where it is on display in the World War 2 gallery, Fall of Singapore section. We’re fortunate that Marsden published a memoir of his wartime experiences (Merciful journey, 2005) that includes a full account of Operation Mosquito) – to Marsden’s story follows: Marsden C. Hordern. - A merciful journey : recollections of a World War II patrol boat man. - Carlton, Vic. : The Miegunyah Press, c2005. [1] 26 July 1943 broke fine and clear, promising a brilliant day. But, as I was enjoying the morning air on the bridge with D'Arcy Kelly, a light blinked from the signal station '811 811 814'. Reg was ordered to report to the Operations Office 'forthwith'. Something was afoot. A special boat collected Reg and a Jeep was waiting for him on the wharf. A couple of hours later it returned with dust flying from its wheels, and a worried-looking Reg climbed aboard. Chips and I met him at the gangway, he motioned us down to the wardroom, flopped into his chair, flung his cap onto his bunk, and swore loudly. 'What a job they've got for us. We're off to bloody Timor and I'll miss the nurses' dance.' That was pretty rough justice: when invitations came for social functions ashore, Reg generally drew the lucky straw. Sydney, NSW. c.1943. Starboard view of HMA motor launch ML814 at speed. [2] His story was this. Together with 815, we were ordered to prepare for an operation-code-named 'Mosquito' - to succour our commandos still holding out against the vastly superior Japanese in Timor. When the Japanese had landed there in February 1942, they had captured and executed some of our soldiers; others had taken to the mountains, where they were carrying on guerilla warfare. Some Portuguese civilians, hiding out with our men in the mountains, were encumbering them, and our task, arranged by a brave and flamboyant Portuguese guerilla leader, Lieutenant M. de J. Pires, was to go and get these people out. Operation Mosquito – map adapted from end paper of Marsden Hordern ‘Merciful journey’, 2005. The Japanese had strong forces in the area, and supporting our soldiers there had already cost the RAN dearly, with the loss of the destroyer Voyager, the corvette Armidale, and many men. About 6 miles west of our rendezvous there was reported to be an airfield; Dili was a Japanese air base, and there were possibly float-plane bases at Maobesi Bay and Besikama, close to our proposed landing point. Our orders were precise. As the Japanese would be listening for radio traffic, we were to maintain strict radio silence. On the way over, a Beaufighter from 31 Squadron would give us air cover for some of the daylight hours until we were close to Timor; then we would be on our own. We were to cross the Timor Sea slowly at 10 knots to save petrol for a high-speed dash home. We were to anchor off an open beach near the mouth of the Dilor River, and would have to row in through the surf to embark the civilians. As well as getting the Portuguese out, we would be taking in food, medical supplies, weapons and wireless equipment, and also landing one or two brave souls who had volunteered to join our commandos there. While Reg was briefing us I thought of the fates of the Voyager and Armidale, and I half wished myself back with my friends in the 110th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, now comfortably camped on Queensland's Atherton Tableland. Next day, Flying Officers Ray Whyte and Bob Ogden from 31 Squadron came aboard for a beer and a chat. Ogden, known as 'Oggie', sporting a large handle-bar moustache, might have stepped straight out of Biggies. They would be covering us for about 200 miles and thought it a horrible assignment: their Beaufighters, armed with four 20 mm cannon and eight machine guns, were not designed for this sort of caper. Their game was to sweep in fast and low, rake their target and get home at top speed, and circling around two Fairmiles crawling across the Timor Sea did not appeal to them. But talking to them gave me confidence until I asked Oggie what he would do if we were attacked by a Zero. He took a thoughtful pull at his glass, smiled, and said that all he could do would be to make one pass at it, wish us luck, and go hell-for-leather home 10 feet above the sea. After considerably more refreshment, the pilots went ashore leaving us in a thoughtful frame of mind. I watched the preparations with butterflies fluttering in my stomach. A big wooden skid was built over the quarterdeck for a 28- foot canvas boat. Outside Timor's surf we would have to push it into the water but, as we would not be able to lift it back and it was too costly to abandon, we must tow it back to Australia, and that would slow us down. Our depth charges, which weighed 4 tons, were removed to lighten our load. Most of our secret code books were sent ashore; they must not fall into enemy hands. Shortly before we left, an intelligence officer came aboard. I met him at the gangway and he gave me a fake Japanese ensign to fly on the way over as a ruse de guerre. I was suspicious, even though sailing under false colours sounded better in French. He did not ask me to sign for the flag and I passed it on to Chips, who was talking signals with D'Arcy on the bridge. They didn't like the sound of it either, and we decided that if we were to be caught, it would be under the White Ensign and not the Rising Sun, reasoning that the Japs had not signed the Geneva Convention and that if they caught us like that they might use blunt swords. As there was no need to worry Reg with such trivia, Chips told D'Arcy not to put it with the 'decent' flags but to 'shove it in the potato locker'. Crew members presenting the fake Japanese ensign [to the Australian War Memorial] yesterday [Friday 7 October 1994] [3] Cyril Alcorn came on board just before sailing time. Regardless of whether we were Catholic, Protestant or atheist, he gathered us around the 2-pounder gun, and in a moving prayer, committed us into God's hands as we were about to 'pass through the waters'. One wag made the crack that the waters were passing through him right then. That raised a nervous laugh, but it helped to know that God was now officially on our side. Shaking our hands, Cyril gave us each a piece of rather soft Comforts Fund chocolate and, remembering the terrible fate of the Armidale's men who had drifted for days on a raft and died slowly, I put mine away for raft rations. Taking our few last letters to parents, wives and sweethearts, Alcorn promised to post them 'if necessary', but assured us that he would be giving them back to us in a week or two. I kept mine for forty years before destroying it, but kept the envelope. Finally, a Portuguese pilot, Baltazar, and Lieutenant G. Greaves and Sergeant Jim Ellwood arrived on board. The two soldiers were members of the SRD, the army's cloak-and-dagger men. During the next few days Jim and I exchanged the stories of our lives and discussed our hopes for the future. I admired Ellwood's nobility: he had already been in Timor and was returning voluntarily to join our men there in the mountains. Soon after we landed him, he was captured and tortured, but he survived the war, and over half a century later we met again and relived old memories. L to R: John Dowey, Jim Ellwood and Marsden Hordern, 2010 [4] At about midnight on 27 July 1943, the two Fairmiles slipped out of Darwin and next day anchored in Kings Cove on Melville Island, close to the ruins of Fort Dundas. We found there a former coaster, HMAS Terka, under the command of Lieutenant Ken Shatwell, who later became Dean of the Faculty of Law at the University of Sydney. He hailed us cheerily as we berthed alongside him to replenish our petrol tanks from drums on his deck, and full of bonhomie and chat, superintended the business with a glowing pipe in his mouth. This shocked us, for we had rigid safety rules about fuelling: rubber-soled shoes had to be worn, lest a spark from a nail on the armour-plated deck should start an inferno, all electrical switches had to be broken and smoking was absolutely taboo. Noticing our concern, Shatwell airily waved his pipe at the Terka'sfunnel, and we took his point. By comparison with the smoke and sparks belching from it above the fuel drums, his pipe seemed innocuous. Kings Cove was a haven of peace, its air full of bird songs, and the next twenty-four hours there were balm for our taut nerves. Three Aborigines arrived in a dugout canoe, inviting us to go crocodile shooting, and Jim and I took a couple of rifles and joined them. Once ashore, they treated us to a memorable display of the hunting skills which had fed their people for millennia. They brought down birds with stones, and showed us how to make little cakes by knocking the tops off an ants' nest, removing a handful of eggs and rolling them in wild bees' honey. We were suitably impressed: ... there is here too a fat grub that lives in the mangrove root and in truth - with sharks, snakes, crocodiles, fish, birds, mussels & roots, this apparently inhospitable country to white men's eyes, can be a veritable larder ... Although these Tiwi islanders-some naked, with tribal cicatrices on their bodies and front teeth knocked out-looked alarming, they were friendly, and anxious to show us the sights. They took us to see a crashed Japanese Zero and the ruins of Fort Dundas, built in 1824 by the order of Earl Bathurst in the hope that Melville and Bathurst Islands would become another Singapore: ... the remains of the fort were a deep moat, square and wide, & an old well and a stone blockhouse now crumbling in decay amid the silences of the Melville Island bush. We found some old glassware and bottles over a hundred years old. At the Mission we met a bluff R.C. Father who teaches these natives a rough and ready form of Christianity. He had brewed some beer of wild honey, hops and yeast-a very potent and unpalatable concoction & quite black. We savoured it without too much enthusiasm, but he knocked off a large tankard and slapped his belly in appreciation. That night the islanders staged a corroboree. Met by furiously barking dogs, we about twenty men from the three ships in the cove-were led into a clearing and sat down to wait: … before long the dancers with balls of eagle feathers about their necks began to arrive. The women and children sat in an outer ring & the show started. The . . . spectacle was accompanied by a rhythmic clapping & a low guttural sound for musical background. The dancing, with wild screams, furious twirlings, and frantic stampings of bare feet on the ground, raised clouds of dust which dimmed the brilliance of the fire and made the trees appear to recede and assume the proportions of ghostly figures, and all the time the clapping and stamping continued. Most of the meanings behind the dances were fairly evident but a bright lad ... translated some for me. There were buffalo, crocodile and shark hunts. Then the dance telling of the coming of a ship, and the women entered the firelit circle and joined the ecstatic dancing of which they never seemed to tire ... towards midnight we made our way back to the boats and out to the ships swinging quietly to their cables in the stream. One of the dances portrayed dog fights between Zeros and Spitfires. Arms outstretched to represent aircraft wings, the dancers made passes at one another, uttering staccato sounds like machine-gun fire. Occasionally one would be hit and would start spinning, still with arms extended, until he lay a crumpled heap on the ground, the firelight flickering on his body. That remains one of the most memorable theatrical productions I have seen - its stage a dusty fire-lit circle, its sound effects the actors' voices, clapping hands, stamping feet and barking dogs. About noon next day we left Kings Cove on our 300-mile crawl across the Timor Sea, the cloudless sky offering perfect visibility for any Japanese reconnaissance pilots. At night, the constellation of Scorpio with its great red star, Antares, arched above our mast. It also shone on the nurses and soldiers dancing and drinking beer in Darwin, and Reg cursed his luck. Shortly after 1 a.m. on 29 July our wireless began buzzing: it must be something important, for we were on radio silence. Tensely, we waited some minutes while the telegraphist consulted his code books and deciphered the message. It finally came as an anti-climax: we were to return to Melville Island to await further orders. We learned later that the Japanese had been closing in on our men on Timor, and Pires, fearing an ambush on the beach, had broken radio silence and deferred the operation. He also asked for desperately needed food. For two days we lay in Kings Cove, biting our fingernails, while the Japanese maintained their pressure on Pires's men. On 1 August, with an easing of the situation on Timor, we sailed again, this time refuelling at Snake Bay on the north coast of Melville Island, and once more launched out across the Timor Sea in perfect visibility. At length Timor's towering mountains loomed on the western horizon, and when an aircraft appeared, we trained our guns on it, challenging it with the Aldis lamp. It was our friend Ray Whyte in his Beaufighter come to hold our hand, and as we trudged slowly on he circled above us. As the long afternoon wore on and the two Fairmiles crept closer to Timor, we draped sacks over the wheelhouse windows to prevent the westering sun flashing warnings to the Japanese. Thinking of the men on Armidale's raft, we also stowed extra cans of water and tins of bully beef in the Carley rafts. The escorting Beaufighter, now over 250 miles from home and getting low in fuel, came round for his final sweep. As he flew about 50 feet above the bridge, the roar of his Hercules engines drowned all conversation, and the roundels on his wings and his cannon muzzles seemed larger than I had ever seen them before. He banked steeply, and a light blinked from his cockpit window. Eight letters only, but all that he could say: 'Good luck'. Then he levelled out, opened his throttles and sped off over the south-eastern horizon to Darwin, leaving the two Fairmiles alone on the Timor Sea. As it was now late in the afternoon, we began to breathe more easily, reckoning that the Japanese air patrols would have gone home too, and I went below to get some sleep in preparation for whatever the night might hold. I had just dozed off when the strident clatter of the alarm bell jerked me awake and the ship shuddered as she increased to fighting speed. Grabbing my Mae West and helmet, I scrambled on deck to find all eyes focused on a Japanese aircraft circling over the northern horizon. Making a leisurely turn, it flew straight towards us. Then, as we watched breathlessly, it turned and flew off towards the island. The pilot had not sighted us in the gathering dusk and was going home. When we were close enough to pick out individual trees on the island, and were, according to Baltazar, heading directly for a Japanese position five miles south-west of the rendezvous, we turned and ran along the shore. Soon we saw a faint blue light flashing the secret letter; then three fires, 50 yards apart, erupted on the beach. This was the final signal our men were to make, but could we trust it? What if someone had been caught and tortured, revealing the secret? What if this was an ambush? The first boat ashore would find out. We anchored just outside the surge, using a Manila line rather than our chain cable, and leaving an axe beside the winch. At the first sign of trouble ashore we would have to cut and run-and bad luck for anyone left on the beach. The engines stopped, and we could hear surf breaking on the sand and smell the spice wafting out from the shore. Chips was the first to go in. We pushed the heavy boat over the stern and he went off with four sailors to land Jim Ellwood and assess the situation. For about fifteen minutes we waited, peering anxiously through the dark. Then he was back, with word that the commandos were ready and waiting for us. Now it was my turn. We loaded the canvas boat with tommy guns, ammunition, food, medicines and tins of two shilling pieces - Australian silver to pay the Timor natives who had lost confidence in Japanese printed currency. I climbed down the scrambling net into the boat and grasped the long steering oar. We wore heavy army boots in case we were stranded ashore and had to take to the mountains; despite my nervousness, it flashed across my mind that we looked like the pirates of Penzance. But no one was singing. Standing in the stern of this heavily laden 28-foot wood-and-canvas contraption, my anxiety was increased by the prospect of having to steer it safely through the surf. Since my boyhood days on Pittwater I had never beached a boat of any kind in such conditions, and I dreaded capsizing. The first surge lifted the boat, hurried us forward and slipped away under the bow, breaking ahead. Several more followed before we were into broken water and, although the surf was low, it was still a job to keep her running straight. Then wild-looking naked figures rushed into the water and hauled us on to the sand. We shook hands and, as the Japanese were thought to be near, exchanged guarded greetings, keeping our voices down. It took some time to clear the boat of its cargo, but while they were working I saw an astonishing sight: two of the men grabbed tins of bully beef, hacked them open with knives and wolfed the contents down like half-starved dogs. Then, ponies appeared on the sand and, while the commandos were loading the supplies onto them, a number of men, women and children walked out from the trees behind the beach and began climbing into the boat. They kept coming until there were too many for safety; with the boat already dangerously low in the water, I told the soldiers 'no more', and standing waist-deep in the water, they pushed the crowd back. Just as we were about to leave, I glanced along the beach, and there, in the shallows, stood a tall old man in a white suit and Panama hat. In my mind's eye he stands there still, dignified and authoritative. He did not call to me, or make any effort to save himself-he just stood staring at the boat, and watching his people go. I could not leave him: I waded quickly back and grabbed him. J-le was thin and frail, I could feel the bones through his shirt. We did not speak: there was nothing to say. Hampered by my weapons and our soaking clothes, I dragged him through the surf, shoved him over the side into the boat beside my oar, and jumped in. The commandos pushed us forward, the sailors bent their backs to the oars and pulled us through the surf, and soon we were into calmer water. Once there, the old man turned and looked back at the island in the starlight. Then he took something from his hand and, giving it to me, spoke for the first time in precise English: 'If you ever go to Portugal, show this.' It was a handsome silver ring inlaid with a rampant gold lion on a field of jade green -perhaps the armorial bearings of some family with centuries of service in the East. Now nothing remained for him but memories. He had lost everything except that ring, and that he gave away. I did not ask his name and I have never been to Portugal, but I still treasure that memory and his ring. After several more boat trips, having embarked all the people we could take, we headed for home, engines at full throttle, using 90 gallons an hour of the precious fuel we had saved by our slow crawl across the Timor Sea. With the heavy canvas boat bouncing astern, we flew along at 17 knots, hoping by dawn to be a hundred miles from the Japanese airfields. Daylight revealed a pathetic sight on the crowded deck: our human cargo were huddled around the guns, lying in their own filth, vomiting and soaked with spray. We cleaned them up as best we could and gave them tea from our chipped China mugs. Soon after dawn a black dot appeared in the sky, and once more we went wearily to our guns. But as the dot grew larger we recognised the stubby hunched-up look of a Beaufighter, and then the blessed blue and white roundels on its wings: our friends from 31 Squadron had come to shepherd us home. At last the low brown blur of Australia appeared on the horizon. We shot through the boom gate, landed our wretched cargo, and returned gratefully to No. 5 buoy. For this operation MLs 814 and 815 were mentioned in despatches and received a salute from the acting Portuguese governor in Timor: Profoundly grateful to Sea Land and Air Forces Darwin for Gallant and Splendidly successful rescue my Nationals under extremely trying circumstances all concerned Stop We are yours to command for the duration to help against common enemy Stop Viva Australia Viva os Aliados. Fairmiles memorial – grounds of the Australian War memorial, Canberra [5] REFERENCES [1] Copies of the book can be purchased from: · https://www.mup.com.au/books/a-merciful-journey-paperback-softback · https://play.google.com/store/books/details/Marsden_Hordern_Merciful_Journey?id=ZwWODwAAQBAJ&hl=en_AU [2] https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C236293 [3] Ian McPhedran “The ensign they refused to fly” Canberra Times, Saturday 8 October 1994: 2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article118290116 . See also: · “Fake Japanese naval war ensign : Sub Lieutenant M Hordern, Fairmile Launch” https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C286097 · “Meeting the history makers, 27 November 2013” [interview with Marden Hordern] https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/blog/meeting-history-makers · “HMAML 814, RANVR - Sparrow Force – Timor 1942-1943 – under false colours?” December 1994 edition, Naval Historical Review https://www.navyhistory.org.au/sparrow-force-timor-1942-1943-under-false-colours/ [4] Nicholas Seton “An essay on the Royal Australian Navy’s involvement in support of the compromised SRD Operations in Timor 1943-1945” September 2019 edition, Naval Historical Review https://navyhistory.au/an-essay-on-the-royal-australian-navys-involvement-in-support-of-the-compromised-srd-operations-in-timor-1943-1945/ [5] https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1222515 ADDITIONAL READING Fairmile ships of the Royal Australian Navy / edited by Peter Evans. - Loftus, N.S.W.: Australian Military History Publications [for the] Fairmile Association, 2002. Ch. 10 “Timor rescue”: 142-148. Hillar Poder “A Merciful Journey …” Ku-Ring-Gai Historical Society Newsletter 40 (4) May 2022: 4. John Perryman “A Fairmile’s secret war” in The Territory remembers 75 years : commemorating the bombing of Darwin and defence of Northern Australia / Northern Territory Government. - Darwin, N.T. : Northern Territory Government, [2017]: 57-65. “ML 814” / Sea Power Centre. https://seapower.navy.gov.au/ml-814 Marsden Hordern “Touching on Fairmiles” in The Royal Australian Navy in World War II: essays on the Australian experience in naval war / edited by David Stevens. – Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1996”: Ch. 15, 166-170.

-

Edward Willis started following 001 7.jpeg , 001.jpeg , 001 9.jpeg and 1 other

.jpeg.9a50f3f63f03601d4c9f18eed8efaf16.jpeg)