-

Posts

505 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

News

Video & Audio

Men of the 2/2

Forums

Store

Gallery

Posts posted by Edward Willis

-

-

-

-

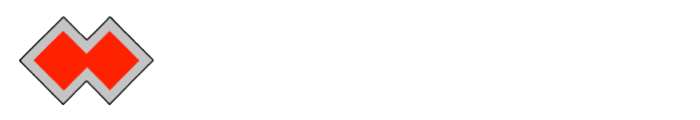

‘The RAAF boys who fell out of the sky’. Sgt John Jones with (mounted) RAAF Sgt Webb and Flying Officer Gabb. [1]

Introduction

No. 31 Squadron was formed on the 14th August 1942. It was to be a long range fighter squadron equipped with Beaufighter aircraft, the first of which was received on the 23rd August 1942. The arrival of the squadron at Batchelor in the Northern Territory on the 27th October improved the RAAF’s fighting potentialities in North Western Area. After a few weeks of intensive training and familiarisation flights, No. 31 Squadron moved to its operational base at Coomalie Creek on the 12th November.

Beaufighters, later to be known to the Japanese as “whispering death”, joined the offensive for the first time during the early hours of the 17th November, when two flights of three aircraft each strafed Maubisse and Bobonaro in Portuguese Timor. At this time the RAAF were implementing a policy of bombing and strafing hostile Timorese concentrations in Timor and encouraging resistance to the Japanese authorities. This policy was translated into action by the combination of Hudson and Beaufighter attacks daily stepping up the number of sorties in Portuguese Timor, culminating on the 26th November in the biggest RAAF operation in this theatre to date, when, ten Hudsons and six Beaufighters from No. 31 Squadron bombed and strafed Hatolia and Beco districts, starting a number of fires in the villages of Nova Lusa and Beco.

In the first two weeks of operations, the Squadron had recorded 53 sorties into enemy territory, the majority of which were strafing attacks. The targets for all these operations were identified and ‘called in’ by Lancer Force HQ on the ground in Timor.

Line up of Beaufighters, Coomalie Creek, 1942

Callinan, by then commanding officer of Lancer Force, previewed the circumstances relevant to the topic of this story:

Meanwhile, the Japanese had driven down and occupied Same in strength and had established a camp at Betano with approximately 300 troops. This was most disconcerting, as from there they were pushing eastward, and had already established daily patrols past the Quelan River area which had been used for the evacuation of the 2/2 Company and the Dutch". [2]

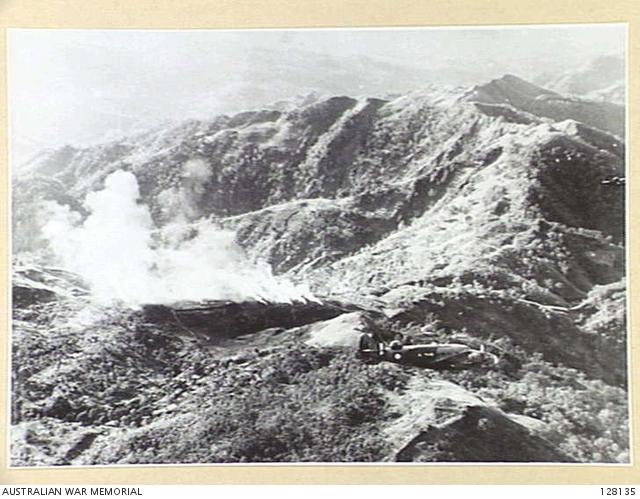

The No. 31 Squadron attack on the Japanese camp at Betano that was initiated in response to the threat just described by Callinan.

Shot Down at Betano

Operation Coomalie 43 of December 29th, 1942 was a strafing attack directed at huts in the vicinity of the near coastal village of Betano, on the south coast of Portuguese Timor, just to the east of the mouth of the Sue River, by four Beaufighters of Number 31 Squadron, Coomalie Creek.

Of the four planes that made up Coomalie 43 – one (COO 434) turned back around an hour after take-off due to failure of that aircraft’s intercom and WT equipment; the remaining three planes continued on to the target, through at times very poor weather.

After eventually locating the target at 2:20 pm, COO 431 commenced their first pass followed by COO 433 and then COO 432 crewed by Pilot Officer Glen Gabb, (21) and Observer/Navigator Sergeant David Webb (22).

COO 432 followed COO 433 in the first run over the target, flying in northerly course at 100 feet height, fired three bursts of cannon and machine gun at some native huts. COO 432 finished this run by turning to the west and is was then that Webb observed the tail fin smashed by fire either from a mortar or Oerlikon gun (he saw a red ball go through tail of aircraft) – the aircraft was also holed in several places in the tail and the port motor cut out.

Remnant of an Oerlikon gun from the wreck of HMAS Voyager. [3] No. 4 Independent Company veteran Rex Lipman states that the Japanese had salvaged the anti-aircraft guns from the Voyager and used them against the Beaufighters involved in the action described here [4]

Gabb then turned the aircraft in an easterly course, and Webb threw out propaganda pamphlets as instructed. The Pilot was unable to maintain height or speed, and after crossing the Quelan River headed the aircraft out to sea.

At this time the speed had decreased to 100 knots and the temperature of the starboard engine had increased to 280° and the controls were acting erratically. Gabb then crashed landed on the sea about a quarter of a mile out to sea off Cape Mati Boot. The tail of the aircraft hit the water first and then the engines – the crew had braced themselves for this crash, Gabb also had moved the gun sight out of the way, and the men quickly escaped through the two top hatches. They climbed onto the wings which were then waist deep, and then swam to the shore.

The Beaufighter sank in about 20 seconds, the front going down first followed by the tail – it is estimated that the aircraft sank in 15 metres of water, at low tide about a 200 metres off the shore near Cape Mati Boot. [5]

[5] Given the fairly precise description of the location of the crash site, the wreck of this Beaufighter should be able to be located.

Gabb and Webb Become Temporary Commandos

The story is taken up again by Callinan:

Then, from company headquarters, came the message that two Australian airmen were with the section posted above Alas. This was rather surprising, as we had not been informed that a plane was missing. Eventually the two men reached us, Pilot Officer Gabb and Flight Sergeant Webb; they had been the crew of a Beaufighter that had strafed the Japanese company at Betano. As they-swept over at tree top height, the Japanese had opened up with everything, and as far as one could judge their tail had been blown off by a mortar bomb.

The pilot had managed to get the plane down in the sea a little to the east of Betano. Then, making slow progress they managed to cross unwittingly and without being observed an area subject to regular Japanese patrols. Then by good observation of scraps of evidence carelessly left by the evacuated (Australian) troops they got on to a track that led them towards Alas. They were fortunate enough to meet a native who willingly gave them some food and directed them towards the Australian position.

These were great fellows and we were pleased to have them at headquarters. They were new faces with new ideas, and we learned from them not a little about the air side of the picture. Also from then on Australia received improved meteorological reports because we gave that duty to Webb who had attended a RMF school in the subject. We were also pleased to get these airmen as they augmented our guard list. Such was our lack of manpower that everybody on HQ staff from myself and Baldwin down did our turn on guard. And now with two additional men it meant that every third or fourth night a couple of us could get a full night's rest. They entered into the spirit of the show very quickly and were most adaptable. [6]

Evacuated To Australia With Lancer Force

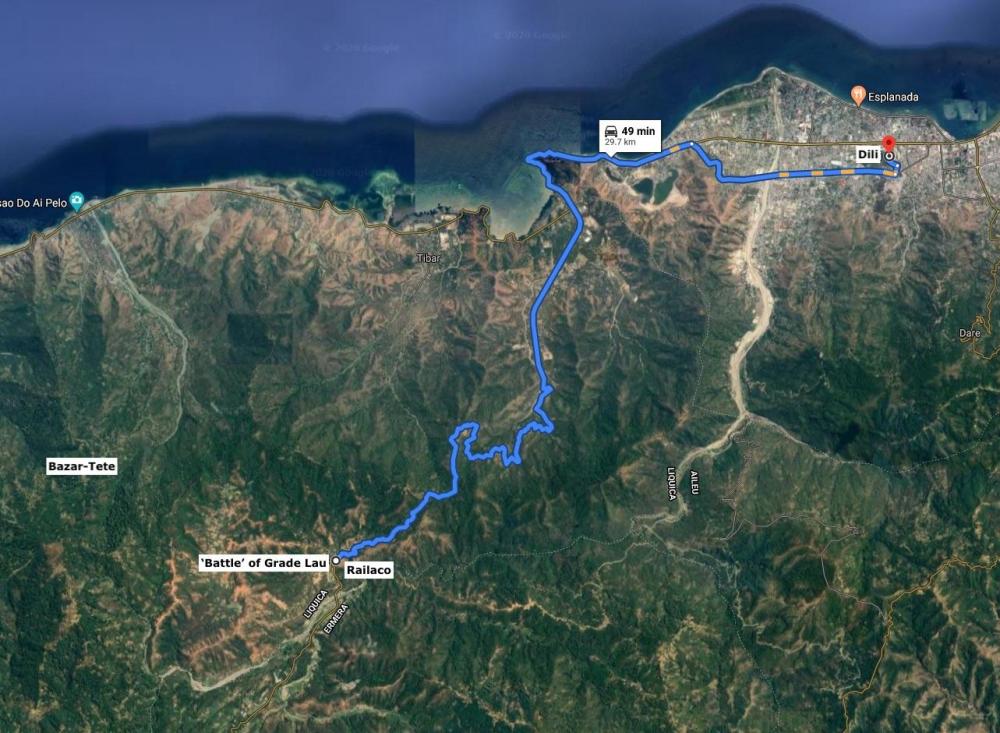

Gabb and Webb’s sojourn with commandos was short lived as their arrival coincided with the decision to evacuate Lancer Force to Australia. The Force’s position had become untenable in the face of increasing Japanese territorial pressure in conjunction with their Timorese allies. The formerly used landing and evacuation sites at Betano and the mouth of the Quelan River could not be used, so an even less desirable location further east at Quicras was selected. The two men staged with Force HQ over three days from Belulic to Fatu Berliu (Nova Anadia) then Cledec to the coastal village of Quicras (Clacoc).

Map of the Gabb and Webb's travels on Timor

On the morning of the 9th January 1943 Lancer Force (now concentrated except for a detachment at Ainaro from whom there was still no word) set out with 50 Portuguese (all they could take of over 100 who had asked to go with them) on the last stage of their journey—over open grass country. It was raining heavily. The rivers between them and Quicras might flood and block them. They had to hurry. Soon after they started a Zero fighter suddenly appeared about 1,000 feet above them. They were afraid it would pick them up, but the pilot apparently noticed nothing. The afternoon march led through swamps, often up to a man's chest. The going beneath the surface was slippery with mud and twisted mangrove roots. But by 5 p.m. the whole party was in the bush which fringed the beach. Exactly at midnight recognition lights from the sea answered the signal fires. The surf was heavy. Boats sent inshore from a destroyer—the HMAS Arunta —were swamped. Time was running out. A few strong swimmers swam out beyond the broken water but reported this manifestly too difficult for most. At last, however, through great efforts, the whole group was ferried on board. The sailors were very kind to them. Most of the soldiers were so tired they slept almost all the way to Darwin where they landed on 10 January 1943.

Both Gabb and Webb had caught malaria and were hospitalised for several weeks before being fit enough to rejoin their comrades at 31 Squadron.

References

[1] Rex J. Lipman. - Luck's been a lady. – Adelaide: [The Author], 2000: 87.

[2] Bernard Callinan. - Independent Company : the Australian Army in Portuguese Timor 1941-43 / introduction by Nevil Shute. - Richmond, Vic. : Heinemann, 1984: 206.

[3] Photographed in Same side street, 1 May 2018.

[4] Rex J. Lipman. - Luck's been a lady. – Adelaide: [The Author], 2000: 87.

[5] Given the fairly precise description of the location of the crash site, the wreck of this Beaufighter should be able to be located. The narrative of the attack and crash landing has been adapted from Garry Shepherdson ‘The losses of Coomalie 43: it could have been a lot worse’ ADF Serials Telegraph News 7 (2) Autumn 2017: 28-33. (http://www.adf-gallery.com.au/newsletter/ADF%20Telegraph%202017%20Autumn.pdf)

[6] Callinan: 209-210.

-

-

-

-

INTRODUCTION

It is the 79th anniversary of the Japanese assault on Dili (February 19-20 1942) that began the almost year long Australian commando campaign against the occupying enemy in, then, Portuguese Timor.

The earliest account of the history of the campaign was written by Bernard Callinan and titled Independent Company and published in October 1953. The book was reprinted in 1984 and is widely regarded as one of the best of the personal WWII campaign histories genre.

Back in 1966 he gave an insightful address to engineering undergraduates at the University of Melbourne (his alma mater) in which he explained how the book came to be written. Callinan developed several ‘threads’ in his explanation with the primary one being ‘therapy’ in reaction to ‘the strain of waging a war against an always greatly superior enemy, and of being dependent for our existence upon a large all-pervading population’. He states that ‘We learnt to live with the strain, but there was a pronounced reaction when we were brought back to Australia’.

He goes on to say: ‘Another strand for the thread lies in our success. We had been successful. MacArthur and others had told us so, but much more we knew it; and we knew we had been successful where others had failed - in fact where all others had failed. No other allied troops between the Philippines, Burma, Malaya and Java had met the enemy and survived. We had killed some fifteen hundred enemy for our own loss of less than fifty but, very much more importantly, throughout it all we had remained a cohesive, aggressive fighting force’.

‘Another strand was the desire to get accuracy to the story. I think I am not unusual because I find the part truth difficult to deal with and trying to the patience. This story was front page news when it was released from censorship, many versions sprang up and the emphases were sometimes on the wrong aspects. I wanted to record my version of the true story’.

And finally this tribute: ‘After the Japanese landed there were a few weeks of doubt, but from then on, the Timorese became our supporters and loyal friends. They looked after our wounded, they buried our dead, they fed and housed us’. Over the months I moved, often unaccompanied, along our 60 mile front and I never hesitated to walk into a strange village, ask them to feed me and then lie down and sleep amongst them in a hut. They could have cut my throat without hindrance if they had wished’.

Bernard Callinan was a Captain and second in command of the No. 2 Independent Company on their arrival in Timor and subsequently took over as Officer Commanding in May 1942 with the rank of Major. In November 1942 he was given command of Sparrow Force at the time it was renamed Lancer Force after being reinforced by the No. 4 Independent Company.

Callinan was a peripatetic commander and travelled frequently and extensively visiting the dispersed locations occupied by the Australians. The book reveals that he was an acute observer of the people, terrain and localities over which the campaign was conducted and recorded what he saw with considerable insight and self-deprecating humour. Given Timor’s underdevelopment, especially away from Dili, many of the scenes he describes in his book are still recognisable today.

Talk To Fourth Year Electrical And Chemical Engineering Under-Graduates

WHY I WROTE ‘INDEPENDENT COMPANY’

Bernard Callinan

UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE, FRIDAY, 1st APRIL 1966

Introduced by professor C.E. Moorhouse, D.Eng. and E.D. Howells, M.E.E.

Dust jacket of the 1st edition of 'Independent Company' [Thank you to Craig Westerndorf for sending this to me - EW]

As I grew up, I heard many ‘old sayings’ from the only one of my grandparents to survive my birth. A very strong charactered old lady who had been widowed early in life, but not lost either her spirit or kindly nature; she had many such sayings which were produced just as often to protect me from just punishments as to point a lesson to me.

The saying that comes to mind is ‘A task begun if half done’; it is particularly applicable when the task is a difficult one. I have such a task today and I had one in the writing of Independent Company as you will learn. But now I have to talk to you on a subject in which you probably have little interest and, more probably, will never know much about.

Professor Moorhouse has been mentioning such a talk to me for years; for so long that I was afraid it might lead us to having to avoid each other to reduce embarrassment to reasonable proportions.

There was a time when he said he would prescribe it to be read. I agreed with this proposal ostensibly because of the suggestion that it would be good for the readers, but actually because it might encourage the publishers to bring out another edition, which would enable me to direct potential borrowers away from my bookshelves to the book stores.

Professor Moorhouse has said that a primary reason in asking me to give this talk was to get, from someone who happened to have passed through this school, an answer to the recurring question ‘why do people write books?’.

I think also he may have had in mind showing you someone who once flogged his way through the school and to encourage you with the thought that ‘if he could do it anyone of you can’.

He may be more kind in his phraseology, but whether this be Professor Moorhouse's reason or not I shall be happier about the strain he has put upon me. If just one of you does get the little extra encouragement needed to produce a book - and I specifically exclude text books from my hope. Text books are only an occupational hazard these days.

Whatever may have been his reason, time has gone by until the original and sundry other publishers have all said the matter is dead; and all I have is the self-flattery which comes from buying second-hand, at more than the original price, whatever copies I can get hold of to replace the copies borrowed, always of course with the most earnest promises to return.

Recently one second-hand book seller telephone to say that he has a rather battered copy which would cost me thirty shillings, about fifty per centum more than the original price. When I expostulated at such extortion, he said he was sorry, but he had had to pay a lot for it because it was autographed by the author.

Time having removed all taint of sordid finance from anything I may say to you I can address myself objectively to the subject given me, ‘Why I Wrote Independent Company’? - as bald and brash a title for a talk as ever there was.

Even the title of the book Independent Company does not help me; it was not a good one at the time and now with ‘take overs’ and company conspiracies many would expect a financial treatise. I selected it as a second choice, the first having appeared on another book a month or two earlier: there is some consolation in the realisation that the first choice would have been worse.

Independent Company was selected because when we went to Timor, we were Number Two Independent Company, but when it came back the unit became the 2/2 Australian Commando Squadron. We thought that the word ‘commando’ had a boastful ring about it, and we preferred the subtle anonymity of ‘Independent Company’ and, in its original conception, the title had been intended to be anonymous.

The first two ‘Independent Companies’ were formed and trained in great secrecy under 104 British Military Mission on Wilson's Promontory, which was given the title of Number 7 Australian Infantry Training Centre. When questioned on the selection of this title for such a Special training project, one of the leaders of the mission replied that he understood there were at the time, only five infantry training centres in Australia so he thought that the enemy would spend so much time looking for Number Six that they might never find Number Seven.

It is interesting that, a little later, Radio Berlin did make an announcement about the special troops Australia was training on Wilson's Promontory, and went on to comment upon how ineffective they were likely to be if they ever did see any action.

The Companies were formed and trained to be independent, they had their own medical officer and section, their own signals and engineer sections, and a much higher than normal proportion of officers and non-commissioned officers. The total strength of a company was something less than three hundred. Every man was expected to be thoroughly trained in his own arm of the service and to be a volunteer for special service before entering on the special training. It was expected that the companies would have to act without the close support of normal army services and were organised, trained and equipped accordingly. As it turned out, we had thrust upon us an independence beyond anything envisaged.

So, having been trained for independence and having fought quite independently of Australia and of the rest of the allies for some months, we had a fondness for the word ‘independent’. But I was wrong to select ‘Independent Company’ for the title, I presumed too much, I should have based the title on ‘Timor’ not on ‘Independent’.

As I attempt to deal with the subject given me, I shall have to gather strands together and if you are patient - and understanding - there may be a thread to be recognised at the end.

I do not think I can avoid spending a lot of time in the first person singular in this talk, and all I can do is to repeat another old saying ‘it hurts me more than it hurts you’; but you may accord this the same doubt as I used to.

I recall a remark of another Bernard with the surname Shaw, who replied when the actress Ellen Terry asked if he would agree to the publication of their exchange of love letters, ‘if you don't mind undressing in public, I do’. I had this awful feeling of revealing myself for all to see just as Independent Company appeared in the book stores, and I have a similar feeling today. However, having braved the earlier exposure I shall have to hope for similar good treatment this time.

I wrote the story of the Australians in Portuguese Timor as I interpreted it because I had to. It was only recently when 20th Century Fox were wondering whether they could do something with the story that a word was applied to its writing which surprised me, but I think it was apt, the word was ‘therapy’. If one word could describe the main reason for its writing this would be it.

In 1943 I came back from twelve months of continuous warfare with its quiet times and its times of intense excitement; but there had been no boredom, because there had always been the strain of waging a war against an always greatly superior enemy, and of being dependent for our existence upon a large all-pervading population.

I have said ‘waging a war against’ because this had been a dominant characteristic of the whole campaign, a small inadequate force protecting itself by attacking the much stronger enemy.

The strain of such a campaign was with us continually; even in what might be called rear areas there was little real relaxation. I might give you an idea of how life passed for us if I tell you that I put nights into three classes:

The usual ones - when you slept fully clothed with your weapon right alongside you.

The good ones - when you took your boots of.

The heavenly ones - when you took off everything with a reasonable hope that there would be no disturbance.

For months on end we all ‘stood-to’ for an hour before dawn. As the bush or tree that you had seen moving and signalling to the unseen enemy became immobilised by the early shafts of light, and the jagged silhouette on the skyline turned into mountains again, you got that reaction which just sapped a little more of your reserves.

We learnt to live with the strain, but there was a pronounced reaction when we were brought back to Australia. One very fine young officer who had done magnificent work there went completely off his head and was taken south in a straight-jacket. [?] My trouble was to get clear of the continuous circus of events which kept running around my mind. I shall come back to this strand again a little later.

[?] Lieutenant John Rose, Signals Section

Other strands are to be found in the factors which dominated the campaign, and I shall endeavour to put these succinctly to you.

This island stretching east and west for about three hundred miles has a north-south width of only about thirty or forty miles and yet it rises to ten thousand feet in a confused tangle of spurs and ridges. The near presence of the large Australian land mass effects the climate so there is little jungle, but there were areas of friendly eucalyptus to help us in our struggle.

The eastern half of the island - as well as a small enclave in the west - has been Portuguese for more than 400 years. We passed through and occupied small towns which have known Europeans for more than twice as long as this city.

There is a heavy population of about half a million Timorese in the Portuguese part, a bright happy mixed Melanesian-Polynesian race of medium height who, in their agricultural pursuits, had cleared large parts of the mountains; so we could stand on a ridge and see friends or foes across the valley and yet know that there was a separation of ten or more hours of intense physical effort.

After the Japanese landed there were a few weeks of doubt, but from then on, the Timorese became our supporters and loyal friends. They looked after our wounded, they buried our dead, they fed and housed us.

Over the months I moved, often unaccompanied, along our 60 mile front and I never hesitated to walk into a strange village, ask them to feed me and then lie down and sleep amongst them in a hut. They could have cut my throat without hindrance if they had wished.

Bernard Callinan on Timor - photograph by Damien Parer

They fed us with whatever they had to spare from their own food, maize, rice, bananas, pigs, goats and occasionally water buffalo. After our stomachs had shrunk to match the quantity we could get, we did not feel that we were faring badly for food. But in fact, we were not far above subsistence level, and certainly not at what would normally be considered adequate or balanced enough for continuous fighting. We learnt to drive ourselves continually to meet the physical demands; I considered myself fit and well at eight stone.

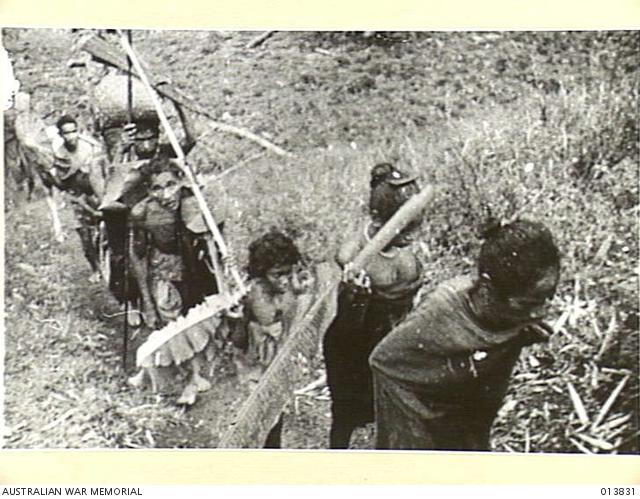

The young Timorese lads vied amongst themselves to become criados to the Australians; that was to go wherever his soldier friend went, accept whatever the war might send, to carry the personal belongings leaving the soldier free to concentrate upon the use of his weapons. As soon as the action started the criado disappeared to re-appear almost mysteriously alongside his soldier as soon as the engagement was over.

Between the Timorese and us grew up a respect and liking that has become deeper with us as the years go by and, I am told, has become legendary with them. Portugal did not enter into World War II, so we and the Japanese fought in what was ‘neutral territory’.

We exchanged notes with the enemy through the Portuguese administration; the Japanese Commander sent his compliments at the same time as he sent an invitation to a rather unequal contest. We exchanged courtesies with the Portuguese, and we learnt to respect and to admire them; not one of us has anything but undiluted gratitude to them and respect for their high standards of honour. Most of the Portuguese were government officials and had onerous responsibilities under these conditions to their post and to their fellow country people; they carried these responsibilities nobly and we would not have survived if they had not helped us. Many of the Portuguese risked death and some died horribly for us.

Here is not the place to elaborate on what I am sure is surprising to you about the Portuguese as it was surprising to us when we met and had dealings with them. I shall say only that, of all those who have carried European civilisation to the east, the Portuguese have by far the most successful record. The Portuguese and Timorese strands in the thread are attractive and strong.

Then there was the steady courage of the Australians - mainly from Western Australia - which changed our role from one of survival to that of the hunter. Our patrols were always probing the enemy and attacking whenever possible. We had a rough rule, if the enemy is only three times your strength attack immediately, if he is stronger attack if you possibly can.

There was one over-riding consideration in our tactical decisions too many wounded men would render us immobile - we could have only the fighting and the dead. The Japanese had this problem to, and they dealt with it logically - they shot their own wounded. We had three badly wounded men whom we guarded and carried over the mountains for three months before we could evacuate them to Australia.

We had sufficient ammunition because we had gone well supplied, and we had supplemented our own with some that we removed from the dump of the surrendered force in Dutch Timor before the enemy could get to it.

When we did establish communications with Australia, we asked for some supplies to be dropped to us from the air; and what we asked for was significant - boots to permit us to remain mobile over those rocky mountains; quinine to alleviate the chronic malaria that afflicted us; and money to pay our Timorese friends for all that they had given us and for what we would need to maintain the fight.

Another strand for the thread lies in our success. We had been successful. MacArthur and others had told us so, but much more we knew it; and we knew we had been successful where others had failed - in fact where all others had failed. No other allied troops between the Philippines, Burma, Malaya and Java had met the enemy and survived. We had killed some fifteen hundred enemy for our own loss of less than fifty but, very much more importantly, throughout it all we had remained a cohesive, aggressive fighting force.

Not even then did we think that we would have done better than those who fought in those other areas, and I do not suggest it now. But we were proud of the Japanese statement in one of their demands for our surrender ‘you alone do not surrender’; and when I returned to Australia I was told by responsible men that the knowledge, in a time of surrender after surrender, that there was a small force still fighting in Timor had given national morale in Australia a significant uplift. Leaving this as a simple statement without the many qualifications it would require it did strengthen my desire to set the story down.

It is easier to tell of success particularly if you are part of it; but this aspect also increased the risks which could come from exposing oneself to the public.

Another strand was the desire to get accuracy to the story. I think I am not unusual because I find the part truth difficult to deal with and trying to the patience. This story was front page news when it was released from censorship, many versions sprang up and the emphases were sometimes on the wrong aspects. I wanted to record my version of the true story.

I should confess also that there was some personal interest in the pursuit of accuracy. I had been in positions which called for decisions, I had helped with some and made others. Some - not all had been good; some, I still think, were original in their concept and I wanted to record the decisions and the circumstances in which they were made. As in many other parts of life - the initial piece of insight is often forgotten in talking of the acts which flow from it. You can place your own evaluation on this strand.

I would add that following some visits in recent years to Vietnam I have taken, after twenty years, a renewed interest in guerrilla warfare. I have read Mau Tse Tung, Che Guevarra of Cuba and Giap of North Vietnam. Each has assembled thoughts on guerrilla warfare in a more orderly fashion than we ever did. Except for their overriding aim of eventual political action they have nothing we did not know and practice; and looking back, if we had not been withdrawn, we would probably have had to depart from our pure militarist approach; the Japanese had already done so. There was one significant difference between us, and the guerrilla forces these masters write about; they rely greatly upon the guerrilla being personally indistinguishable from the surrounding population; we were always distinguishable and proudly so.

I have given you the main strands which went to form the thread, but there are a few more and these will be revealed if I tell you how the story became a book.

Towards the end of 1943 I was commanding an infantry battalion in what was then Dutch New Guinea and is now West Irian. We were at Merauke on the south coast in what is one of the largest swamps in the world, rivalling that of the Amazon. There was some fighting, but it was mainly in the air or between patrols which bumped into each other as they struggled through hundreds of miles of swamp.

Apart from occasional visits of inspection to out-lying posts, my tasks were mainly administrative, and so the story of Timor could still go round and round in my mind like circus ponies. Then I started to write the story in pencil on sheets supplied for letter writing purposes. These I sent to my wife for typing - the task had been begun.

It has always seemed significant to me that I did not start to write at the beginning of the story; I started in the middle because this was the part which was always foremost in my mind. If I had not started there, I would never have written the story at all - once I had this out of my mind the other parts grew around it and I gradually wrote both ways from this central part - the beginning had indeed been half the task.

What was it I wrote about first - and why? It was the ‘August Show’. In August 1942 the Japanese determined to remove this enemy which had annoyed them for six months, killed about a thousand and had rallied behind them the population both Portuguese and natives. They collected the necessary forces and drove at us with five lines of attack, two from the north, two from the west and one landed from the sea, came from the south behind us and overall was their air force. This we held off - but only just - we survived and followed the Japanese back to their bases.

There was much courage and fateful decisions were made in those ten days and it would take too long to deal with them now, but those days were coursing through my mind then and for years after: they are often not far below the surface even now. This, first of all, I must get off my mind.

Over the months the story grew into a typescript and I gave it the title ‘False Crests’ because as we crossed and re-crossed the tangled mountains which reach ten thousand feet, we were led on to heartbreak by the ‘false crests’. With near exhaustion as a constant companion it was a test of mind and character to struggle on time after time reaching what ‘must be the top’. This crossing and re-crossing of tangled mountain spurs was a physical strain, but an even greater mental strain.

The typescript was read by Major Stuart Love about whom I must tell you a little. A one time under-graduate of this University he went to England about the turn of the century to study mining engineering. In addition to following his profession in sundry parts of the world, he had led an expedition through Arnhem Land in 1910, served with the Royal Engineers in France in World War 1 and had been decorated with the Distinguished Service Order and Bar, Croix de Guerre avec palme, and was three times mentioned in despatches. He had also Studied Renaissance art in Florence and could lecture interestingly and informatively on it; he was a recognised Chaucer authority and had written poetry in English, French and Spanish.

Stuart Love had helped to train us at Wilson’s Promontory and, strange as it may seem, his contribution had been not so much towards toughening us mentally or physically as in showing us a fine understanding approach to men and particularly to natives. His contribution to our training played quite a significant part in building up and maintaining the loyalty of the Timorese to us - without this we would have perished.

Stuart Love had followed the Timor story with deep insight and interest; he saw applied successfully the principles inculcated whilst we were training under him. He wanted to know the story as fully as it could be told, and my version was the only one there was.

Now, we move on almost ten years to 1952, and in those intervening years, Stuart Love had pressed me from time to time to ‘do something about that story’, but the pressures of re-establishing a professional practice, of coping with an increasing family and, what I did not realise at the time, of recovering from six years of war, did not give me many opportunities.

Then one day Stuart told me that he had arranged through a friend to get a copy of the typescript for himself if I would agree to it being re-typed. I agreed without hesitation; possibly with the hope that the requests ‘to do something’ would now cease. I did not take note of who the friend was; I was told, but it did not register with me.

Later that year Stuart told me that his friend had returned from his long trip back to England, but the re-typing had not been completed as they had hoped; however, his friend had read parts of it that were lying about, and he thought that it should be published.

I then realised that the friend was Nevil Norway, an aeronautical engineer, who has left a partial autobiography with the title Slide rule. Norway wrote books under his two first names of Nevil Shute, of these you have probably heard. The rest of my path to publication could be described briefly by saying that Nevil Norway was at that time Heinemann's best selling author, and Heinemann's published Independent Company with an introductory chapter by Nevil Shute.

Before Heinemann's made their decision to publish, the typescript had to be recommended by their ‘reader in Australia’ - the author Paul McGuire - and subsequently be further assessed in England. The arrangements for these were made in Australia by an old English gentleman named Bartholomew, who had spent a lifetime with Oxford University Press; and I think, beneath his inexhaustible courtesy, he hid a difficulty he had in not viewing is out here as brash colonials.

Bartholomew telephoned me to say that Mr. McGuire had approved of False Crests for publication and that the typescript would now be sent to England for a final decision. By then I was becoming alarmed at the additional work that might be thrust upon me, so I asked how long this would take - the longer the better for me. Bartholomew explained with every courtesy, that if it had been Mr. Norway's manuscript, it would go as quickly as possible by air mail; but, of course, mine would go sea mail. I think he was surprised when I laughed; however, he telephoned a few days later to say that although the cost had been enormous, they had sent the typescript by air mail; and he did not quite hide his disappointment when I was not elated.

In England the decision to publish was made promptly and so I took Stuart Love and Nevil Norway to lunch to talk over what would happen from then on. I can still remember vividly sitting on a club sofa between these two charmingly pleasant, but very literary persons, while they discussed the need to polish up the English in the typescript.

I had written as the need drove me and as opportunity permitted without any thought of literary polish; and I had drifted into this matter of publication with a vague belief that publishers and some sort of fairy amanuensis who turned rough typescript into smooth flowing impeccable English. As Nevil talked my belief was shattered and Stuart confirmed that the English was undeniably rough.

I saw myself being drawn into a complete re-editing and I sank into silent despair until, almost doubting my ears, I heard from Nevil the comment that after all it had a certain ‘freshness’ and possibly it would be better to leave it as it was - and that is how it is.

It had been agreed that the story needed to be set into its place in the World War II panorama and Nevil Norway agreed to do this. He wrote a long introductory chapter and he took considerable care to be accurate. He circulated drafts to people such as the official war historian, Gavin Long, our initial commander in Timor, now Sir William Leggatt, Stuart Love and myself; by the time I had received his fourth draft I was thoroughly depressed by the knowledge of my own single draft - comparably I should have been into double figures.

This introductory chapter of Nevil's raised for him possible difficult problems of publishing rights, fees and copyright; so he placed the whole matter before his agents in London and when he had their reply, he sent me a copy. The crucial part of the agent's letter was the opinion that, as Colonel Callinan could not possibly afford to pay for the chapter at Norway's usual per line rate he, Norway, might as well donate the whole thing; which was what he had intended.

One or two more strands are worth gathering. I kept no dairy in Timor. Conditions were not conducive and the possibility of the enemy getting it by capture or death made it foolish to have tried. But in 1943-44 my memory for places and dates was clear; however, I became filled with fear as the publication date came nearer. I was greatly relieved by the comments from my comrades in arms which had the theme ‘how did you manage to keep all the records you must have had to write that?’ There was none at all, and this is not a facility that I have had at other times in my life. You may see some significance in this.

I purposely avoided comments on personalities in what I wrote, and the absence of this enlivening strand is a serious omission from any book. I would think the chief characters go through the pages like disembodied spirits with labels upon them. Where did they come from, where did they go, what were their personalities? I doubt whether I had the high literary ability necessary to give them the bodies and the personalities they carried so clearly for all to see in Timor; and I still do not think that, even if I had been so endowed, it would have been right for me to have attempted it. They were my comrades, some my very close friends; we were all, and as the years go by become more so, bound together by a common unforgettable experience. It would have been misleading to have given only strong points and would have been wrong for me to have attempted to portray a times of weakness and of indecision; it was sufficient to say, ‘they were there’.

Timor was a time of trial for all of us and the intensity of the trial built up in each of us a clarity of thought and perception; we all knew our own weaknesses and we had no desire to parade any strengths if we had any. I had been one of those there and I wrote as such.

The thread made from these strands appears to me to be more utilitarian than decorative as might be expected from an engineer. There are not many bright colours; mainly browns for the khaki we wore; greens for the courage of soldiers, Portuguese and natives; some red for the he of sacrifice again of soldiers, Portuguese and natives, and one bright steel strand for the shining loyalty of all. The national colours of Portugal are green and red, and they are well represented amongst my strands.

What happened to this book? The first printing of 6,000 - four for Australia and two for England - appeared in October 1953 and was substantially sold out before Christmas. A further printing of 2,000 was released in February 1954 and sold fairly promptly; the next printing came out four months later to end the effort. It was widely reviewed and very few adverse criticisms were made; the best review was a long one on the editorial page of what was then one of the best London dailies. It formed the basis for the official war history of the Timor campaign being quoted at length by Wigmore and McCarthy in two volumes of the history. I have wondered sometimes this reliance upon it was too great and whether other views might not have been canvassed more thoroughly. It has been translated into Portuguese and is compulsory reading for the Portuguese army.

I would like in later life to attempt another book. I have no idea of the subject - but if this does not eventuate, as is probable, I shall remain forever grateful and humble because I was given a part in the story, the opportunity to write about it, and the good fortune to have friends who took it to publication.

It is not a great book; others might have made it one - I could not, but it is ‘mine own’. When I exposed myself to the public my friends clothed me with their charity.

Posted by Ed Willis

20 February 2021

-

Dear Ed,

Thank you for your suggestion to submit a funding proposal for 2/2nd to contribute to the Veterans Training Centre, Daisua, Same. I have completed the submission as below.

Our successful implementation of this will be our partnership with Veterans Care Association, AHHA Education and the Timorese Veteran Foundation in TL/Same. As a result I have copied in CD Singh from AHHA, Gary Stone and Colin Ahern from VCA and Ambassador Ines Almeida from the TL Embassy. I have also copied in MP for Stirling, MP Vince Connelly, who has been highly supportive of our cooperation in Timor-Leste.

This will be a remarkable project. The more funding, the better the outcome, better tools, better safety - please push for as much as feasible - Govt spending doesn't look like it is coming any time soon. This budget would buy a few pieces of large machinery in an Australian Mens Shed. With our incredible partners in TL, the money will have maximum effect on the ground as has been demonstrated by all that has been executed so far in the wider VTC project. I was thinking we could paint this building red and paint the double diamonds on the side.

Please let me know if there is further that I can provide. I have updated the website that has detailed reporting of the project over the past two years. We can get this done pretty fast.

Warm regards,

Michael Stone

Michael Stone

Program Director, Timor Awakening, Veterans Care Association Inc.

Honorary Consul of Timor-Leste, Queensland - Australia

T: +61 421 013 740 (Australia) T: +670 7771 9597 (Timor-Leste)

e: michael.stone@tlembassy.net e: michael@veteranscare.com.au

w: www.timorawakening.com2:2 CDO Association Grant Proposal Trade Skills Workshop - Veterans Training Centre Same.pdf Veterans Training Centre Same VCA Report No 1 Jan 2021.pdf

-

INTRODUCTION

Dutch airmen who escaped to Australia after the Japanese invasion of the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) were brought together to form Dutch squadrons under RAAF command. First among these special squadrons was 18 (NEI) Squadron, formed at Canberra on 4 April 1942. Although nominally made up of Dutch nationals, the RAAF supplied many co-pilots, air gunners, bombardiers, photographers, and ground staff. The US provided supplies and equipment.

In December the unit moved to MacDonald airstrip in the Northern Territory and began transforming the undeveloped site into a workable airbase. From January the squadron commenced offensive operation missions over East Timor and the Tanimbar and Kai Islands.

During a raid on Dili on 18 February 1943 a Mitchell aircraft was forced down at sea. The crew, later rescued by HMAS Vendetta, explained that the pilot and bombardier had been killed in the attack.

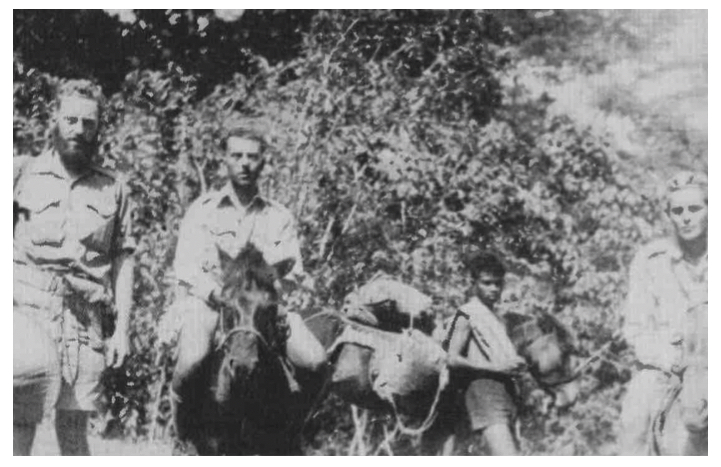

This terrific story of courage under fire and persistence was told by WWII aviation historian Robert Kendall Piper in an article published in the January 1984 issue of RAAF News and is republished here.

ESCAPE AND EVASION

They didn't dally over Dili [1]

By Robert Kendall Piper [2]

Little Willy of Dili was a Japanese pilot famous for his daring attacks on the B-25 Mitchells of No 18 (NEI) Squadron during World War II.

In fact, the mixed Dutch and Australian crews had encountered him on their very first mission when they bombed Dili with nine aircraft on January 18 1943. Beside him all other Zero pilots were second rate and Little Willy always pressed home his passes with enthusiasm and vigour. The Americans in long range B-24 Liberators had also met him when overflying the area. History does not record who dubbed Willy with his title but Allied intelligence sources at the time thought he was the commanding officer of the enemy fighters at Fuiloro 'drome, on the eastern tip of Timor.The No 18 Netherlands East Indies squadron was formed at Canberra in April 1942 within the framework of the RAAF and under their operational control. Initially, there were 242 Dutch and Javanese members as well as 206 Australians. Some of the former were ex-KLM and KNILM crews.

Captains of the aircraft were always Dutch with the RAAF often acting as co-pilots, air gunners, navigators, bombardiers, photographers and ground crew. The cost of operating the unit was met by the Netherlands Government in exile, which also supplied the aircraft. But the squadron was largely equipped and maintained by the RAAF.

Sometimes known as the unit with two commanding officers, the RAAF men were responsible and disciplined under their rules and senior officer, while the Dutch answered to theirs. Official notices were posted in both languages even though all the Dutchmen spoke English with varying degrees of fluency. It was an unique establishment, but it worked! The squadron operated throughout the former Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia) flying unescorted missions both day and night.

Stationed first at MacDonald and later Batchelor, in the Northern Territory, medium-level attacks were launched against enemy-held towns, ports and air bases with occasional low level sweeps for shipping. Supply drops to guerrillas in occupied territory were also made.

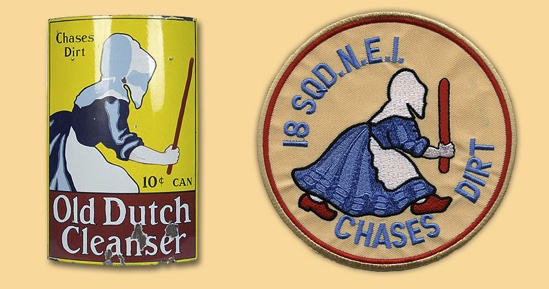

Their unofficial badge, ‘The Dutch Cleanser’, featured a Dutch housewife in traditional dress sweeping up with a large broom. Numbering on the aircraft consisted of three digit serials with the prefix ‘N5’, painted in white.

Throughout the war the popular and robust North American B-25 Mitchell was the only aircraft used by No 18. Eventually, 150 served with this and No 2 Squadron (RAAF) during the conflict.

On February 18, 1943, two flights, each of three aircraft, had been ordered to attack shipping, the aerodrome and general Dili area. Designated MacDonald Operation 15, it was marred by one of the squadron's Mitchells being shot down into the sea by a persistent Zero, thought to be none other than Little Willy.

The six aircraft left MacDonald 'drome at 7.25 am local time and climbed to the planned cruise altitude of 10,000 feet. Each B-25 carried three 500 lb bombs as well as 34 small incendiaries. Weather was fine and warm with 20-30 miles visibility, except above the mountains of Timor and over the target, where half the sky was covered by stratus cloud. Unfortunately, there was not to be enough of the latter for evasive action by the allied planes.

Two Zeros were sighted as the Mitchells made landfall on the inward run. Both were at the same height as the bombers and passed west to east without attempting to intercept. The enemy fighters apparently were content merely to shadow the B-25s. Four more Zeros were sighted again, to the rear and above, on the final approach to the target. Diving over Dili to pick up speed, the Mitchells pattern-bombed a heavily camouflaged 6,000-ton ship moored opposite the former Customs House.

It was surrounded by power launches, which scattered in all directions on the bombers' approach. Nil results were observed despite the entire bomb loads of the six Mitchells being dropped. Intense Bofors and heavy anti-aircraft fire was encountered from the land defences and entire length of the ship.

A pair of drab-green Zeros closed in behind the B-25s at the end of their bombing run, as they swung south for the trip back home. At this stage Two Flight was leading One Flight by about four miles. All Two Flight's top-turret gunners fired on the leading fighter as it began to attack. It seemed the Japanese pilot was hit, and the tail of his plane shot off. The Zero was last seen falling into the hills at the back of Dili, near the former Governor's residence.

Both flights now descended into cloud cover and closed up for improved defence. The remaining fighter tagged along at a safe distance, above and between them. Obviously, he was relaying their progress and position back to base.

Three more Zeros joined the one following, near the south coast of Timor. Splitting into pairs they re-commenced attacks on each B-25 flight. Approaches were made above and to the rear from the four to eight o'clock positions.

As the island passed behind them the bombers, now at 2,000 feet, raced for home over the sea. Forty miles out from shore, One Flight's gunners also scored a Zero. The Mitchell crews saw it break off and head back smoking heavily. There seemed little chance of it reaching the coast safely.

The B-25 pilots now adopted the evasive tactic of weaving each time they were approached. At the same time their gunners began firing at ranges out to 1,200 yards to keep the fighters further at bay. It seemed to have the desired effect as the incoming Zeros were now breaking off at 600 yards.

But one determined Zero pilot, when the battle was 100 miles out to sea, closed to 60 yards and shot out the port engine of aircraft N5-144 with his cannons. Return fire from the Mitchell gunners' tracers appeared to strike the attacker but he flew off apparently undamaged. Undoubtedly this was the audacious Little Willy.

The same Zero now made five more attacks from directly above and out of the clouds. FSGT W. S. Horridge (RAAF), mid-upper turret, discovered to his horror that his guns had jammed.

Pilot of N5-144, Lieutenant B.J. Grummels (NEI), as well as the RAAF bombardier/nose gunner SGT R. J. Tyler, were killed by machine-gun fire in the first overhead pass. Dutch co-pilot Ensign C. M. Fisscher, although wounded, immediately took over the controls and called for help from the other five Mitchells.

The next three vertical attacks were thwarted by Fisscher. Each time the fighter came in the co-pilot swung the nose guns of his staggering B-25 towards him. At the same time SGT Horridge followed around with his weapons, making a pretence of firing. The Zero pilot broke off.

But in the final pass the fighter had pressed close home, hit the starboard engine, aileron and a rudder, which tore off. By now the rest of the Mitchells had seen and heard what was happening, returned to help and drove off the Zero, which headed back to Timor.Although N5-144 lumbered on for another 20 miles as its remaining engine steadily lost oil pressure and power, it was by now practically uncontrollable. Wind howled through the bullet holes in the front Perspex, making it almost impossible for Fisscher without goggles, to see.

At 10.50 am the bomber skidded into the sea tail first and lower turret stilt down. Fisscher and the engineer. SGT W.L. van Hoek (NEI) escaped by sliding side windows near the pilots' seats. Although both wounded, they managed to launch a rubber dinghy. The aircraft sank in two minutes. This gave Fisscher just time to smash in the top turret Perspex with his hands and drag out, aided by van Hoek, the top and bottom gunners.These airmen were also wounded, the former seriously, but to make things worse they had also been knocked about in the crash landing, were dazed, resisted rescue and had to be forcibly extracted. As the last man was hoisted clear and hauled into the dinghy the Mitchell slid below the surface.

In the rubber boat Horridge and Van de Weert (NEI), the lower gunner, were laid in the bottom while Fisscher and Hoek sat on opposite sides. The B-25s overhead, low on fuel, only had time to circle quickly and take a bearing before heading off home.

Within ten minutes a shark broke the surface, rose across the edge of the dinghy and snapped at the co-pilot's back. He and the engineer beat the water to frighten it off and then also retreated to the bottom of the boat. By six that evening three RAAF Hudsons of No 13 Squadron found the downed airmen and dropped supplies. Their attention had been attracted by the men in the dinghy igniting five of the six flares on board.The RAN destroyer Vendetta hove into sight at 1 am the next morning, guided by the survivors' last flare. All aboard the dinghy were safely retrieved and subsequently recovered from their ordeal and wounds back at Darwin.

History is vague about what eventually happened to Little Willy of Dili. Rumour has it though that a RAAF air gunner, on his first engagement, eventually sealed the Zero pilot's fate. Since that day nobody saw or heard of Willy again, which seems to prove that perhaps the claim was true. Anyway, that's the way the story goes ….

The Dutch engineer, van Hoek, was awarded the Dutch Flying Cross and Ensign Fisscher received the RAAF's Air Force Cross, both as a result of the action on that fateful day.

Sergeant ‘Tim’ Tyler, the RAAF nose gunner/bombardier who was killed, was posthumously honoured by having an airstrip officially named after him. It is just north of Daly Waters in the Northern Territory.

Japanese historian and writer Professor Ikuhiko Hata recently advised that the unit which attacked the Mitchells was the 59th Sentai (Army) flying Oscars (Nakajima fighters), not Zeros. Two pilots participating in the attack were Lieutenant Kuwata and Sergeant Shinichi Kubo. The latter, an ace, was credited with the downing of N5-144 and later went missing over Wewak the same year.

JAPAN. 1945. JAPANESE AIRCRAFT, NAKAJIMA Ki-43 "OSCAR" FIGHTER IN FLIGHT. SINGLE ENGINE, SINGLE SEATER, LOW WING MONOPLANE. (DONOR: MR PETER SELINGER)

REFERENCES

[1] ‘ESCAPE AND EVASION’ (1984, January 1). RAAF News (National : 1960 - 1997), p. 16. Retrieved January 28, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article259010183

[2] Robert Kendall Piper was a researcher and author of many articles and several books on World War II aviation and topics related to the Pacific War. As a young man he lived in Port Moresby and learned to fly in Papua New Guinea (PNG). He later became the official Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) historian for 15 years then worked with Veterans Affairs for another 12 years before retirement. He was also involved with studies of aircraft crash sites and erecting memorials. Since the 1980s he wrote for Australian newspapers and Flightpath Magazine and conducted research as ‘Military Aviation Research Services – Canberra’. He was the author of two books: Great Air Escapes (1991) and The Hidden Chapters (1995). See https://pacificwrecks.com/people/authors/piper/index.html

-

WWII in East Timor – A Site and Travel Guide

Commando Campaign Sites

ERMERA MUNICIPALITY

ATSABE

8°55′28″S 125°23′54″E

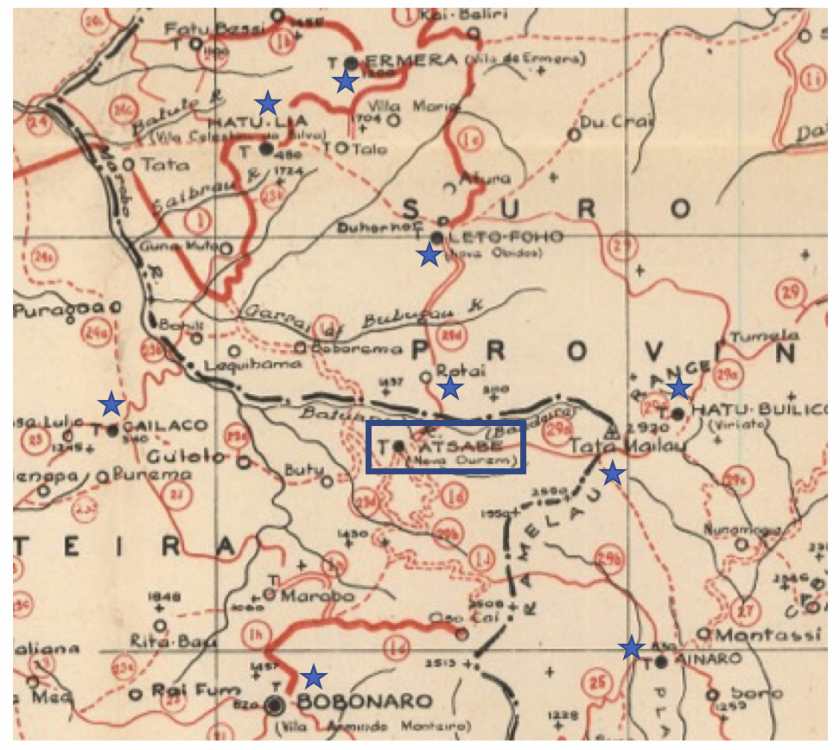

Atsabe’s location in relation to other sites mentioned in the text [1]

Atsabe (Nova Ourem - See Map No.7) is 9 miles (14 km.) at a bearing of 28° from Bobonaro. Atsabe is one of the larger postos and market centres and its buildings number about 20 in all. These stone buildings, most of which have galvanized iron roofing, comprise posto and administrative block, church, school and about 15 Chinese shops. About one mile (11/2 km.) along the Lete-Foho road six bamboo huts with thatched roofs are the native soldiers' barracks. These huts are about 10 feet x 10 feet (3 m. x 3 m.) and are evenly spaced. The posto is well covered from air observation and is well timbered on the southwest side. There is a large market square north of the posto, and many trees have been planted around the trading area. There is a motor road to Bobonaro which for one mile, has good air cover. Atsabe was the Australian H.Q. of a platoon from May to August, 1942. [2]

SIGNIFICANCE

Atsabe sits at an elevation of approximately 1,500 metres on the western slopes of Mount Ramelau. During WWII it was in a key ‘crossroads’ position overlooking important roads and tracks heading in all directions of the compass.

1. NORTH through Rotai and Lete Foho to Ermera.

29d. Track Atsabe (Nova Ourem) to Lete-Foho (Nova Óbidos

Distance, 11 miles (17 1/2 km.). Time taken, 6 hours.

With roads out of commission this is a very important track. An excellently graded track, suitable MT, though subject to landslides and with little cover from the air, leads down to the Bandeira River. From the river there is a steep climb to Rotai, situated on the rugged saddle between Mts. Daralau and Catrai. Again, the track descends with little cover to the Garrai River, after which there is a very steep climb to Lete-Foho. There was a wooden bridge across the Bandeira River. The track is a good one for ponies. [3]

Ken Piesse of the 2/4 described this segment in notes he prepared for that unit association's visit in 1973:

"Leaving Ermera, the road leaves the Ermera-Dili road after about 2 miles and goes up a 1-in-10 grade following a crest of a ridge before turning southwards along a valley before winding up to Lete Foho about half way between Ermera and Atsabe. It possesses the usual posto, Chinese shops etc. and was burnt out following bombing in August 1942. The road goes on past Rotai, where there is said to be an impressive cave. Rotai was shelled and burnt by the Japanese, but the Chefe Rotai kept A Platoon HQ high above Rotai at the village of Alsai near the summit of Mt Catrai (7,100 ft.) supplied with food up until late November 1942. Tourist pamphlets suggest an investigation of the Bandeira waterfall from the road between Lete-Foho and Atsabe. Atsabe ‘a pretty town and well cared for’ (page 83 ‘Independent Company’) whose Chefe de Poste, Senhor Alexandrino was a good friend of the 2/2nd and C platoon 2/4th, an excellent handler of the Timorese and incidentally, an excellent armourer, the reason he was known to the Australians as ‘Krupps’. Atsabe is one of the larger postos and market centres and late in 1942 was the centre of the 2/4ths 7 section operations". [4]

2. NORTH WEST to Hatu-Lia

A road at one time connected Atsabe with Hatu-Lia. Owing to washaways and lack of maintenance, this road is untrafficable to MT [Motor Transport]. It could possibly be put into repair with suitable labour and equipment in a short time.

From Bobonaro to the south coast the only means of transport is by pack animals along made tracks. There are no MT roads.

Natives reported that the Japanese were using M.T. from Bobonaro to Dili in December 1942. [5]

Callinan described utilising this track with Don Turton:

"TURTON and I arrived at Atsabe in the afternoon, and the Doctor [Dunkley] made us comfortable. We stayed that night and the next day. Boyland was there and I got from him the details of his dispositions. On the following morning we set out for Hatu-Lia. There was a road from Atsabe to Hatu-Lia that was closed to wheeled traffic by numerous washaways, but it made travelling on horseback quite easy. The road was very well graded and wound in and out of the gullies and around the spurs so that the actual distance travelled was much longer than the distance between the towns. We had horses, but I was quite pleased to arrive at our destination". [6]

Shortly afterwards, Dr Dunkley and Don Turton traversed the same route in more testing circumstances:

"While here we heard of Signaller Gerry Maley, who had been wounded above Hatu-Lia when the Japanese had first entered that town. He had remained at the telephone there until the enemy were very close to the town; he had then established an observation post overlooking the town, from which he had seen some troops approaching and, thinking they were Australians, had signalled them. Not receiving a reply, he had become suspicious and took cover behind a tree, but a burst from a machine gun shattered his thigh. The other two with him had been unable to move him further than to a native village, and now the Japanese had heard of his hiding place and were searching for him. At this time there was a small post overlooking Hatu-Lia, but the Japanese were between the post and Maley's hiding place, and while a patrol was being arranged to go in to get him, Dunkley and Turton set off from Atsabe, and after a really marvellous piece of work in dodging Japanese patrols succeeded in rescuing the wounded man and bringing him back to Atsabe". [7]

3. SOUTH to the regional southern provincial capital of Bobonaro

ATSABE TO BOBONARO:

This comparatively short section of road crosses and recrosses broken ground with many creeks and re-entrants for 8 to 10 miles (13 to 16 km.). There are many hairpin bends and sharp turns along this stretch of road. Until it turns west and traverses a ridge crest it would present difficulty to any MT of 30 cwt. or over, and other reports state that certain repair work would be necessary before use. Along the ridge crest, to Bobonaro, a distance of about 7 miles (11 km.), it is fairly easy going; the steepest grade would be about 1-5 or 1-6. There is practically no air cover. [8]

Heading further south from Bobonaro, a track traversed via Mape, Lolotoi and Maucatar to the vital south coast anchorage at Suai.

4. EAST through Tata Mailau (Ramelau) to Hatu-Builico and then on to Maubisse

Looking eastward, a high track traversed the peak of Tata Mailau and linked Atsabe with Hatu-Builico then onward to Maubisse.

29a. Track Atsabe to Hatu-Builico to Tumela:

Time taken, 8 hours.

The track, which is approximately 15 miles (24 km.) in length, crosses Ramelau Range, after a long climb at nearly 10,000 feet (3,000 m.). The track to Mt. Tata-Mailau is very steep in places. Good air cover. Once the range has been crossed there is a 6 ft. (2 m.) track, constructed, but very steep in places, for the whole distance down to Hatu-Builico. The track then climbs a gentle slope to Mt. Tumela at the junction of the Lete-Foho-Hatu-Builico (29) and Maubisse-Hatu-Builico (29a.) tracks. This track crosses the greatest mountain barrier on the island. The going is very exhausting for both ponies and porters, but the track is reasonably graded. [9]

Callinan described the terrain along this track:

"… the cool precipitous alpine country between Hatu-Builico and Atsabe in the Ramelau Ranges, where the timber was very similar to the woolly butts of the Australian Alps". [10]

5. SOUTH EAST to Ainaro

29b. Track Ainaro to Atsabe:

Distance, 12 miles (19 km.). Time taken, 7 hours.

The track leaves Ainaro in a north westerly direction and crosses rice fields and riverbeds with very little cover. Leaving the flats, the track climbs tortuously up the Ramelau Range until it joins the Bobonaro-Atsabe road at the saddle. The track is very difficult to climb, and cover is poor. [11]

6. WEST to Cailaco

Atsabe could also be approached on tracks from the west:

23d. Track Cailaco to Atsabe, Marobo to Atsabe:

There are several native tracks between Cailaco and Atsabe and Marobo and Atsabe. All are very difficult to cross as they pass through the large Atsabe rice fields. All portions of the tracks join the old roads and then depart from them cross-country again. There is practically no cover from the air. [12]

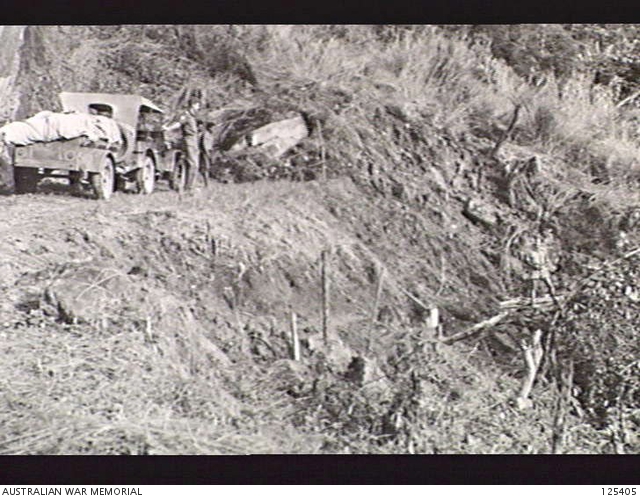

MUREMA, PORTUGUESE TIMOR. 1946-01-25. THE MILITARY HISTORY SECTION FIELD TEAM HALTED ON THE ROAD TO ATSABE BY A LANDSLIDE. SERGEANT G. MILSOM IS STANDING BY THE JEEP AND LIEUTENANT C. BUSH, OFFICIAL ARTIST, IS STANDING ON A TEMPORARY BYPASS (RIGHT). (PHOTOGRAPHER SGT K. B. DAVIS) [13]

EVENTS IN ATSABE

Japanese First Probes South

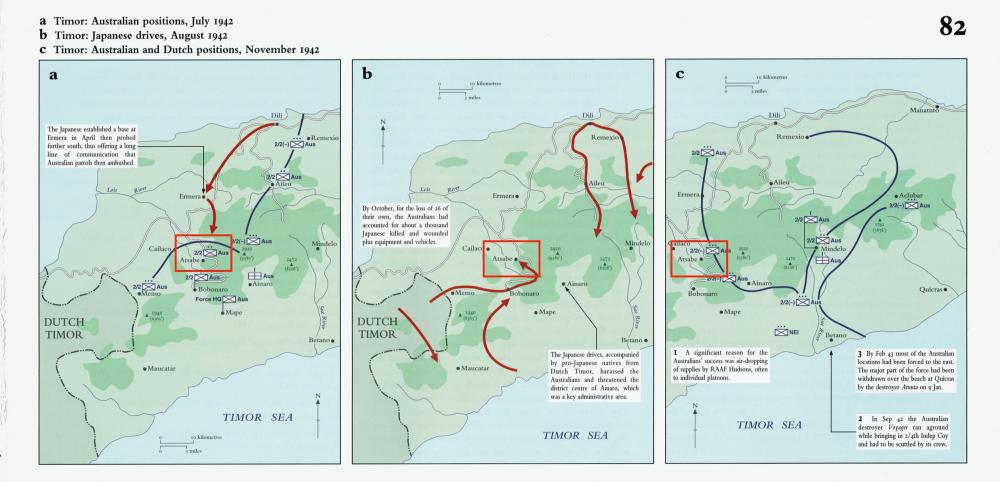

"[In mid-April 1942] It became clear that the Japanese were interested in moving up the roads which led to Ermera and Hatu-Lia. During the days following, the swift-moving Australians clashed sharply with the advancing Japanese and claimed 30 or 40 killed, without casualties to themselves, before the invaders occupied Ermera. Outflanked, the guerrillas then withdrew and later, from Villa Maria, watched the Japanese feeling out along the road towards them. By 9th April, however, these feelers had coalesced into a movement by about 500 men towards Hatu-Lia and the most forward commandos fell back to Lete-Foho. But the Japanese pressed farther on and, on 13th April, after shelling the little town they occupied it and once again the Australians fell back. What really worried them, however, was uncertainty as to whether the invaders would stop at Lete-Foho or would press on to Atsabe or still farther to Ainaro — and menace the Australian bases. In the event, however, the forward movement not only ceased at Lete-Foho but, by the end of April, the Japanese had all withdrawn to Ermera and Dili, having suffered annoying losses to the harassing tactics of the guerrillas". [14]

Atsabe as key objective during the campaign [15]

Patrolling From Atsabe

“Meanwhile [by mid-April] we had developed a system of patrols which came up through Lete-Foho, moved across to Boyland by night, and then around through the Hatu-Lia area on the lookout for stray lone Japanese patrols, and finally back to Atsabe; the complete circuit took approximately a week. There were a large number of Japanese troops milling round in this area, and often one of their patrols would be allowed to walk through an ambush position because our position was itself covered by another patrol higher up. Portuguese reports placed the number of Japanese troops based on Ermera as not less than twelve hundred”. [16]

D Platoon Based on Atsabe

“…. by the end of April, an extensive Australian redeployment had been almost completed. Laidlaw's platoon was carrying out a wide and difficult movement to establish themselves at Remexio, fairly close in to Dili; Boyland's platoon was settling in the Maubisse area; a new platoon (‘D’), which had been formed from the Independent Company's sappers and from the fittest of the survivors from Dutch Timor, had been gathered at Mape and given a short intensive course of guerrilla training, and by early May, would be based on Atsabe under the command of Turton, who, though gentle by nature, was already proving himself an outstanding soldier and guerrilla engineer; Baldwin's platoon (which had been scattered widely to fill gaps as they developed) was to have the left flank positions in the general area of Cailaco”. [17]

Callinan Appointed to Command the Company

“I was in Atsabe when I received the message of my appointment to command the company and I was, of course, pleased. I had been given plenty of freedom and opportunities to move around, and to put forward suggestions which had always been given consideration, but I entered into my own command with considerable enthusiasm. It was the twentieth of May. I was very fortunate to take over when everything was in good condition. Turton and his platoon were now in position, and Rose was having a well-earned spell.

I proposed setting up my headquarters at Atsabe, where I was well placed to watch the danger area around Ermera. Ainaro would have suited me even better, as it was more centrally located on our sixty-mile line, but it did not have the telephone connections that Atsabe had. The centre of the area for the telephone system, as for everything else, was Bobonaro, but it was half a day's journey further to the south, and away from the centre of activities”. [18]

Reserve Arms and Ammunition Transported to Atsabe

“The ammunition left near Hatu-Lia was still within striking distance of the enemy, and had not been safely hidden, so Callinan told a small party of men to pay the Timorese to help move the stores to a safer place. One of the men whom Callinan relied on to carry out this crucial task was not a senior officer or even an NCO; it was a lowly ranked sapper, or private, in the engineers corps, Vincent Wilby, 20, from Bendigo, Victoria, had met Callinan years before when he worked for a short time as an assistant in Callinan’s drafting office, and Wilby had joined Callinan on his journey into Dutch Timor. While returning to Portuguese Timor, Wilby had acquired a team of Timor ponies that he had stolen along the way. Callinan later admonished Wilby for taking the ponies, insisting that he should pay or at least promise to pay for any property that he acquired. These first few ponies proved to be very useful, forming the nucleus of the transport corps used by the 2/2 Company”. [19]

“Wilby personally took part in six return trips to Atsabe, each leg taking about a day, traversing the rugged terrain on narrow walking tracks, until they reached a hiding place just outside Bere Mau’s [Wilby’s creado] home village. Some of the journeys started early in the morning and took until late in the evening; others went through the night. The hiding place was located about 200 metres from the town in a cave. The cave could only be entered by going through a ravine, and then up a steep slope. Over the course of six weeks, the pony train hauled a steady stream of ammunition—over 100,000 rounds of .303 bullets for rifles and Bren guns, 45,000 .45 inch bullets for the Tommy guns, and 2,000 grenades”. [20]

Atsabe in the ‘August Push’

“Mobilising the ‘Black Columns’ was a particularly effective innovation. The Japanese used them like human shields, driving large numbers ahead of their soldiers and into the Australian and Dutch positions. The militias drove a wedge between the Australians and the Timorese population, and as the Dutch and Portuguese Timorese were ethnically the same, it became impossible to tell friend from foe. The Japanese thrust targeted the Dutch force near the south coast centre of Maucatar, forcing them to completely abandon their positions and flee towards the east".

"Dexter’s A Platoon, based in the Fronteira Province, responded to the Japanese drive from Dutch Timor by blowing bridges and roads to slow the advance. As the Japanese and Timorese surged over the border, A Platoon fought a series of running battles as part of a staged retreat into the mountains around Fronteira. The attack from the west threatened the cornerstone of the Australian operation in Timor, the province of Fronteira which was run by the avidly-partisan administrator Sousa Santos. The Japanese assault made Sousa Santos fear for his life, and he abandoned his post and fled to the eastern provinces with his wife and young daughter”.

……

A Platoons Fighting Withdrawal to Atsabe

“Dexter realised that he risked being encircled. A Japanese drive from the south was also coming his way, so he ordered his less mobile men—the sick, the signallers, a medical orderly, and men with supplies—to withdraw to the east to Atsabe, where they would link up with Don Turton’s D Platoon, which had established a defensive stronghold. Atsabe, at the foot of 3,000 metre high Mount Ramelau, was the place where much of the 2/2’s store of ammunition had been stashed after being hauled up the mountain by Wilby’s pony train in March. As Dexter made preparations to stage another ambush on a narrow pass linking the road from Bobonaro to Atsabe, a local elder, Chief Martinho, approached him with a surrender note distributed by the Japanese. Martinho told Dexter that the Japanese were advancing towards him with big guns. Dexter’s party of 28 men contacted the approaching enemy briefly before they withdrew and joined the flight to Atsabe”.

Turton’s ‘Hideout’

“Upon reaching the town, Dexter and his group learned that the Japanese were already there, so they climbed further up into the mountains, departing within minutes of the Japanese opening up on the town with mortars and artillery. Eventually Dexter regrouped at Turton’s ‘hideout’—a group of huts perched on a very steep hilltop—where the hungry men dined on a meal of grilled buffalo as the Japanese continued shelling the deserted nearby town. Joining the exodus to the cold and hungry high country was Callinan’s headquarters, which set up a new base on the western slope of the Ramelau range on the night of 13 August”.

"The Australians faced an increasingly brazen militia force of Black Columns from West Timor who were prepared to throw themselves at positions. The Black Columns seemed well trained as they swarmed upon the defensive positions of A Platoon, sometimes under the cover of fire from Japanese mountain guns, other times without. One of Dexter’s Bren gunners was forced to shoot three attackers with his hand-gun in self-defence. The use of the militia forces by the Japanese completely changed the nature of the conflict; it now meant that in order to survive these engagements the Australians would have to shoot and kill indigenous people who might only be armed with spears". [21]

End of the ‘August Push’

“As the push continued into the middle of August, the Timorese population took to the hills, taking with them most of their food and farm animals. The four platoons were now constantly on the run and they were getting hungrier as each day went by. By 15 August, after six days of relentless fighting, the Australians had been driven by troops and artillery into a ‘pocket’ formed by the highest peaks in the centre of the country— Maubisse, Hatu-Bulico, Ainaro, and Samé. In order to deal with this threat, Callinan created a ‘striking force’ by combining C and D platoons to deliver a ‘strong blow to the enemy column advancing through Aileu’. A Platoon, which had been engaged in the most intensive fighting, was to remain in the rear of these platoons in order to prevent an enemy encirclement via Ainaro. The commanders put observers along the Atsabe–Ainaro track so that they would be alert to any enemy movement from the rear".

"Three days later, on the evening of 18 August, a green flare went up over the central mountains around Ramelau, where the Australians had been driven … . After seeing this flare, the Australians believed this signalled the start of the final phase of the Japanese drive. Many of the men, sensing that they would have to stand and fight against overwhelming odds, had a deep sense of foreboding about the following day, believing that it might be their last”. [22]

No. 4 Independent Company Takes Over

“In early October, C Platoon [of the No. 4 Independent Company] was spreading out over the south-western sector of the Company's operational area in Portuguese Timor. Platoon HQ moved from Hatu Udo to Ainaro on 15 October. Detachments located at Maubisse, Hatu Builico, Nunamogue, Atsabe, Beco, Cassa (native name Lias) and Cablak, performed the roles of monitoring all movements of Japanese troops and hostile natives in the sector. They harassed them whenever possible and kept open the lines of communication of ‘A’ Platoon in the north western sector”. [23]

Through October-November 1942, the Japanese continued to increase their force strength in Timor, deploying four or five battalions in the drive towards the eastern part of the island. Faced with loss of food supplies and suffering from malaria, 357 members of the No. 2 Independent Company were evacuated successfully in three trips between 11 and 19 December along with 192 RNEIA and 69 Portuguese evacuees by the Dutch destroyer Tjerk Hiddes.

Meanwhile the No. 4 Independent Company were left to bear the full brunt of actions mounted by the Japanese-led Black Columns. By December, however, the over position of Lancer force was extremely vulnerable especially owing to loss of access to vital food supplies as the Japanese pushed further east. By this stage, the Japanese had mobilised some 12,000 men and had successfully occupied all anchorages the north and south coasts east of and including Beaco.

Ian Hampel’s Recollections [24]

“But the Japs were giving a little bit of trouble gradually creeping back from Dili towards Atsabe which was our only base. So, we had to try to hunt them out. Just below Atsabe though, where the road goes down fairly steeply, there’s a pretty big cliff and at the bottom of that cliff a gully there filled with jungle. We had the job of trying to hunt the pro Japanese natives out of that area. Well, we should never have tried it because that was their territory and they knew how to handle it very well indeed.

Well, we tried to creep through there and of course they were shooting at us from the cover of the foliage down below while we were at the top shooting down at them”.