-

Posts

618 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

News

Video & Audio

Men of the 2/2

Forums

Store

Gallery

Everything posted by Edward Willis

-

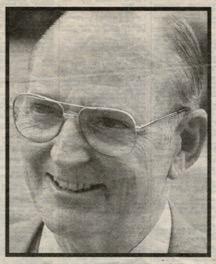

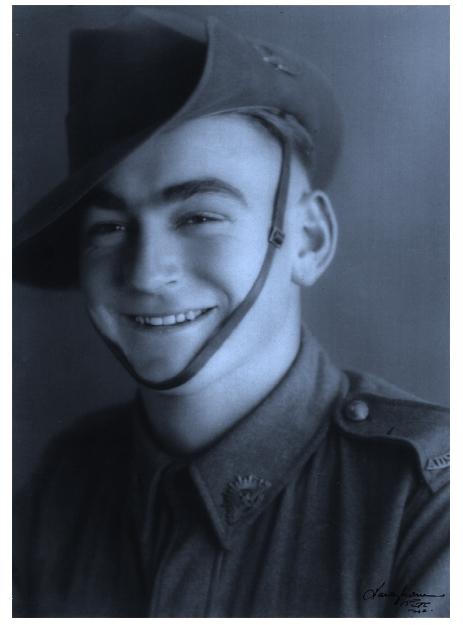

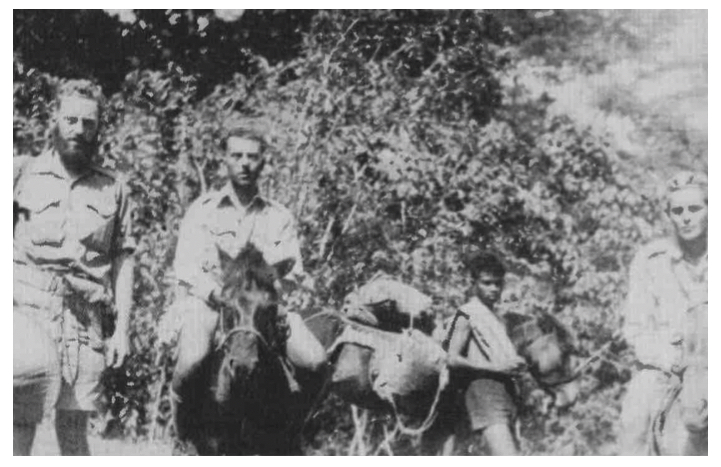

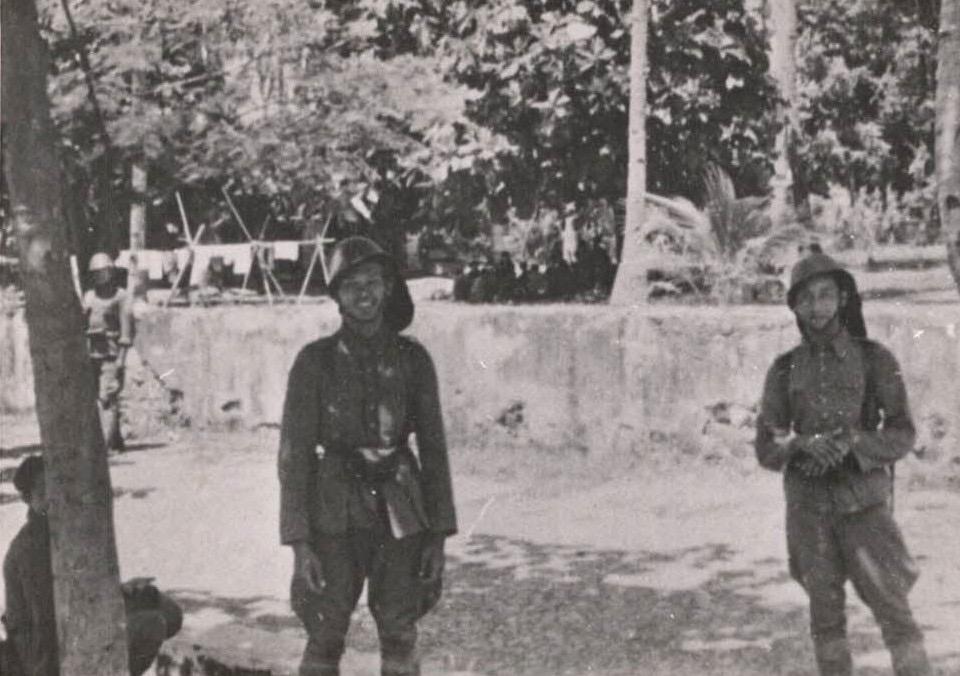

‘What the bloody hell is happening in Portuguese Timor’ INVESTIGATION MISSION TO DILI 8 January 1942 INTRODUCTION (Edwin) Harry Medlin (1920–2013) was Deputy Chancellor of the University of Adelaide from 1978 to 1997. [1] As a young man he was commissioned in 1939 and was serving as a Lieutenant in the 2/1st Fortress Company Engineers at the time Sparrow Force took up defensive positions around Koepang in Dutch West Timor in mid-December 1941. He was captured by the Japanese and held as a prisoner of war in Timor from 23 February 1942 and transferred to Batavia in Java in September 1942 until he was freed on 23 September 1945. Medlin wrote in detail about events in Timor, especially in relation to the action, but also before action and afterwards, including his life as a POW in Timor and Java; his objective was to 'set the record straight' about what he believed to be serious errors of omission and fact in all accounts of the history of Sparrow force in Dutch Timor, and his first-hand account provided valuable insights. [2] In early January 1942, prior to the Japanese assault on Timor, Medlin was a member of a small Allied (Australian/Dutch) mission that travelled from Koepang to Dili in Portuguese East Timor to investigate a report that the ‘… Portuguese Governor has complained that Allied Commanders, particularly the Dutch, are behaving in a very high-handed manner and are requisitioning extensively, impressing foreign residents etc. [and] that fresh troops are being disembarked and that Governor is in state of high indignation’. HARRY MEDLIN RECALLS THE MISSION TO DILI Medlin’s recollections of the mission follow [3]: Wigmore [4] reports on a conference in Koepang on the evening of 15 December 1941 between Mr. Niebouer (Dutch Resident at Koepang) [5], Ross [6], van Straaten [7], Leggatt [8], Detiger [9], Commander of the Soerabaja (5644 tons), Wing Commander F. Headlam (C.O. RAAF squadron) [10], Major A. Spence (OC 2/2 Indep. Coy.) [11] and staff officers. The decision was taken to occupy Dili because Japanese ships were said to be in the vicinity. Wigmore then describes negotiations with the Governor of Portuguese Timor (Manuel de Ferreira de Carvalho) and the subsequent occupation by Australian and Dutch troops. There is no record anywhere that I can find of the next development which, it was said, arose out of a curt telegram from the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill. Portugal (like Sweden and Switzerland) was neutral during WW2, and it suited the (Northern Hemisphere) antagonists’ purposes to preserve that neutrality. Portuguese troopships were said to have been coming from Lorenzo Marques in East Africa. The hearsay catalyst is said to have been the cable ‘Highest British Political Authority demands to know what the bloody hell is happening in Portuguese Timor’. Athol Wilson [12], a Melbourne lawyer, led the Inquiry in Dili. I was chosen as Staff Officer to Major Wilson. I assume that Wilson was chosen because Leggatt, although also a lawyer, had been involved in that initial decision to occupy Portuguese Timor. Although I do not recall the date, I believe it to have been about 10 January 1942, but it might well have been later because photographs show me with a ‘tin hat’ and air raids did not start until 26 January 1942. Fokker aircraft of the type used to fly the investigation team from Koepang to Dili We flew in a 3-engine Fokker with ‘pusher’ engines; we were camouflaged from above and flew extremely low to evade possible Japanese fighters. There were two pilots and three passengers namely Wilson, Headlam and Medlin. I have photographs of Wilson, Ross, van Straaten and Spence in conference and with (Capt.) Callinan [13], Medlin and (? Mr.) Whittaker [14] in attendance. I have other photographs taken that day including one of a small Japanese ship tied up at a jetty in Dili Bay. I think that I know that the recommendations were that our occupation was justified, and that the Dutch presence was no long-term threat to Portugal. In the final event the Japanese invaded the whole island and demonstrated a complete contempt for Portuguese neutrality. There is no reference by Churchill even in his history, The Second World War, nor of any concern for Timor except to comment [15] (v.4 The hinge of fate, p.128) upon its loss to the Japanese. I repeat that I find it, at best, strange and possibly somewhat sinister that there is no record either of Wilson’s inquiry or of his report. The Inquiry was conducted -- I was there - and I knew Athol Wilson well enough to know that there was a Report. WHERE IS IT? Medlin recorded another recollection of this event: [16] Senior officers always have to have junior officers around, looking after their needs and what not, so I went. We met with Major Spence who was the commanding officer of 2/2nd Independent Company, and the governor of Portuguese Timor, and as I say I have taken photographs in the plane and we flew very low because we were camouflaged from above, not below and there was a risk of being shot down by Japanese fighters. And I believe that the conclusion of Athol Wilson and of the governor, and of the Dutch was, that although Dili had been occupied there was no long-term risk of the sovereignty of Portugal over Portuguese Timor. Now I have tried myself to find a copy of that report, I knew Athol Wilson well enough to know that there would have been a report, but it could find nothing. But you have triggered me into remembering this, I will look again, there will be a report somewhere, and I know enough about the army to know that they never destroy anything, not openly anyway. So that was that. Well, I think I said before, when the Japanese landed, they took no account of Portuguese neutrality, and the Independent Company just withdrew and harassed them from the hills. PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORD OF THE MISSION Harry Medlin notes that a camera was in his possession during the mission and he took photos at various times featuring the participants and street scenes and aerial views of Dili. As Medlin himself appears in some of the photos, Athol Wilson probably took some of them. These images provide a unique and valuable record of the occasion; the personal photos are remarkably candid and evocative. [17] 1. Major Athol Wilson (rear), unidentified soldier (front) 2. Frank Whittaker (Australian Naval intelligence officer) (left), Dutch officer Lieutenant Jan Zijlstra (right) 3. Frank Whittaker (Australian Naval intelligence officer) 4. Wing Commander Frank Headlam (left), Lieutenant Harry Medlin (right) 5. Lieutenant Harry Medlin (left), Wing Commander F. Headlam (RAAF) (right) 6. David Ross (Left), Lieutenant Colonel Van Straten (right) 7. Left to right – Lieutenant Colonel Van Straten, Major Athol Wilson, David Ross, F.J. Niebouer (Dutch Resident Koepang) 8. Major Alexander Spence (left), Lieutenant Harry Medlin (right) 9. Portuguese artillery piece 10. Portuguese artillery piece close up 11. Dili street scene 12. Dili street scene 13. Dutch soldiers 14. Dutch soldier 15. Japanese spy ship Nanyei Maru 16. Dili harbour 17. Residence British Consul, David Ross 18. Dili street scene 19. Aerial view Dili 20. Portuguese military barracks, Dili (Dutch HQ) 21. Dili street scene 22. Rua de?, Dili 23. Aerial view Dili (Taibessi?) 24. Aerial view Dili Harbour 25. Aerial view Dili 26. Sunset, Port of Dili THE DOCUMENTARY RECORD OF THE MISSION Medlin is correct in asserting that ‘… there would have been a report’ submitted on the mission but the documentary record is patchy and difficult to locate. The earliest relevant document located thus far originated on 26th December 1941: DEPARTMENT OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS CABLEGRAM 2648, sent 26th December 1941 TO BRITISH CONSUL, DILLI. C.G.S. has been informed by Sparrow force through Army channels as follows: ‘Dilli position most unsatisfactory. Governor organising troops who may harass our troops and will certainly assist any Japanese landing. Van Straaten awaiting instructions Dutch headquarters. Essential to take military control and disarm Portuguese. Delay through political negotiations becoming dangerous. Urgent.’ Inform Commander of Australian forces that on other hand Portuguese Governor has complained that Allied Commanders, particularly the Dutch, are behaving in a very high-handed manner and are requisitioning extensively, impressing foreign residents etc. that fresh troops are being disembarked and that Governor is in state of high indignation. You will observe that this is [a] complaint which reaches us from U.K. via Portugal. I am greatly surprised that you have not sent regular reports as I have asked. We desire urgently your comments and suggestions on above. In particular what restrictions or censorship are being imposed upon Portuguese authorities. MINISTER FOR EXTERNAL AFFAIRS [18] On the next day, the following signal was received by Sparrow Force; note the reference to ‘highest political minister’ that connects with Medlin’s recollection of the stimulus for the mission: To Sparrow Force From Army Melbourne MC4088 27/12 Immediate For OC SPARROW stop Your message 27/12 through DARWIN regarding situation DILLI stop Whole message now being considered main body highest political minister officially informed essential SPENCE OC no contact ROSS and last named forward his views immediately. [19] No documents have so far been located that specifically refer to the establishment and conduct of the mission though Medlin’s recollections and subsequent reports confirm that it actually took place; for e.g., the No. 2 Independent Company War Diary entry for 8 January 1942 recorded: … Visit to Dili by NEI resident from KOEPANG. PORTUGUESE GOVERNOR has reported adversely on behaviour of NEI and Australian commanders in requisitioning Portuguese property and impressing foreign nationals, particularly NEI commander. This report which has just reached Dili has surprised all – at the same time as he sent report off – told Colonel VAN STRAATEN that the behaviour of the occupying force had been good. The opinion of interested persons have that Colonel VAN STRAATEN, who has CO of Force, carried out all negotiations with governor, has been most restrained, in spite of lack of cooperation from Governor. 15 natives arrived at company HQ for work on shelters. [20] Prime Minister John Curtin communicated the findings of the investigative mission to the British government on 10 January 1942: PRIME MINISTER'S DEPARTMENT CABLEGRAM. DECYPHER TO SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DOMINION AFFAIRS, LONDON 0.985 0.986 0.987 DATE SENT: 10 January 1942 No. 38. Repeated to Governor of the Straits Settlement for Commander in Chief, Far East, No, 3, and Prime Minister of New Zealand No. 18. SECRET. TIMOR. Your telegram 25th December No. 895 paragraph 1. Ross reports that allegations against occupying force attributed to Governor entirely without real foundation and that no serious complaint had been made by any inhabitants including foreign nationals now under restraint. No Portuguese property other than open land has been requested. Ross adds that complaints to Lisbon referred to are even contrary to the views expressed personally by the Governor to the Dutch Commander. In his opinion complaints are nothing more than an attempt to stir up trouble and influence political negotiations. No restrictions of any sort have been placed on Portuguese authorities who are at liberty to send and receive any radio messages on Government business. Whole attitude of Dutch Commander has been one of extreme courtesy and consideration oven when latitude allowed has been abused and petty obstructive tactics employed against him. CURTIN Copy sent to Dr. Evatt, Mr. Forde, Col. Hodgson, Mr. Shedden 13.1.42 [21] The British Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs responded to Curtin’s message two days later (12 January 1942): ‘Ross’s reports as to allegations against the Allied Force noted’. [22] REFERENCES [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Medlin [2] Peter Henning. - Doomed Battalion: mateship and leadership in war and captivity - the Australian 2/40 Battalion 1940-45. – 2nd ed. - [Exeter, Tasmania]: Peter Henning, c2014: 7. [3] Dr. Harry Medlin ‘Timor and Java’ https://studylib.net/doc/9066385/timor-and-java---the-recollections-of-lt-harry-medlin: 11. [4] Lionel Wigmore. - The Japanese thrust. - Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1957. (Australia in the war of 1939-1945. Series 1, Army; v. 4) - Ch. 21 ‘Resistance in Timor’: 469. [5] Mr. F.J. Nieboer, Dutch Resident (Governor), Koepang 1941-42. [6] Mr. (later Group Captain) David Ross, British Consul, Dili, Portuguese Timor, 1941-42. [7] Lieutenant Colonel N.L.W. van Straten, Commanding Officer, Dutch contingent, Portuguese Timor 1941-1942. [8] Lieutenant Colonel W.W. (Bill) Leggatt, Commanding Officer, 2/40 Battalion, also original Commanding Officer Sparrow Force, 1941-42. [9] Lieutenant-Colonel W.E.C. Detiger, Commanding Officer, Dutch Timor and Dependencies Territorial Command, 1941-42. [10] Wing Commander Frank Headlam, Commander, No. 2 Squadron, Penfoei, Dutch Timor 1941-42. [11] Major Alexander Spence, Commanding Officer, No. 2 Independent Company, Portuguese Timor, 1941-42. [12] Major Athol Wilson, Commanding Officer, 2/1 Heavy Battery, Koepang, Dutch Timor, 1941-42. He died of wounds 20 February 1942 at Klapalima, Dutch Timor. [13] Captain Bernard Callinan, 2nd In Command, No.2 Independent Company, Portuguese Timor, 1941-42. Callinan was in fact not present at the meeting. [14] Mr. F.J.A. (John) Whittaker, Civil Aviation clerical officer, British Consular Office, Dili, Portuguese Timor, 1941-42. In mid-April 1941, the Director of Naval Intelligence proposed appointing an officer to Dili ostensibly in the role of a Civil Aviation clerical officer – citing an Australian War Cabinet agendum (No.109/1941 – February 1941) that directed their military intelligence services should arrange ‘for special watch to be kept by them on the peaceful penetration by Japanese into Portuguese Timor … ‘. The Australian Naval Board concurred and coordinated with DCA for a naval intelligence officer – Paymaster Lieutenant F.J.A. Whittaker, to operate ‘nominally as a clerk to assist Mr David Ross’ and ‘who would, in the guise of a civilian, be able to discharge the Naval Intelligence duties required of him’. See Navy Office, Memorandum 018820 - 43/85, Melbourne, 28 April 1941 (NAA: 981 TIM P 6, p.57; NAA: B6121, 114G). [15] Winston Churchill. – The hinge of fate. – London: Cassell & Co., 1950: 126. [16] ‘Edwin Medlin (Harry) - Transcript of interview Date of interview: 8th March 2004’ Australians at War Film Archive http://australiansatwarfilmarchive.unsw.edu.au/archive/1503 [17] These photos were in the personal papers of Sir Bernard J. Callinan and were kindly made available to the 2/2 Commando Association of Australia archives by his son Nicholas. [18] 26/12 War Cabinet Agendum - No 270/1941 and supplements 1-3 - Occupation of Portuguese Timor - NAA_ItemNumber11294556 2.pdf – NAA, A2671, 270. [19] Sparrow Force war diary, message received 27 December 1941 – Australian War Memorial RCDIG 1024692. [20] No. 2 Independent Company War Diary 8 December 1941 - 16 December 1942. An entry in Colonel Van Straten’s dairy covering this period also provides confirmation: Furthermore, the ashes in Lisbon are burning quite violently, which even resulted in an official complaint via London, whereupon the GG (Governor-General Sjarda van Strakenborgh Stachouwer) sent the resident of Koepang (Niebouer) for an investigation, which, however, was entirely in my favour. Source: E-mail from: Gerard van Haren to author sent Thursday, December 23, 2021 10:13 PM. [21] War Cabinet Agendum - No 270-1941 and supplements 1-3 - Occupation of Portuguese Timor - NAA_ItemNumber11294556.pdf – NAA A2671, 270/1941. [22] Occupation of Portuguese Timor - (File 1) to 30-1-1942 - NAA_ItemNumber170185-2.pdf. – NAA A816, 19/30. Prepared by Ed Willis Revised 9 January 2022

-

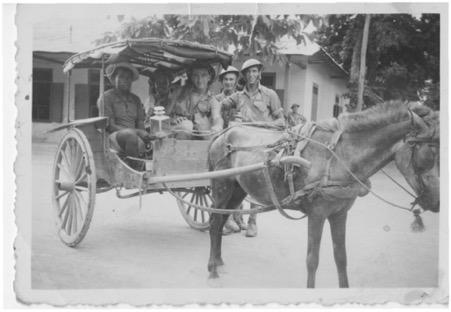

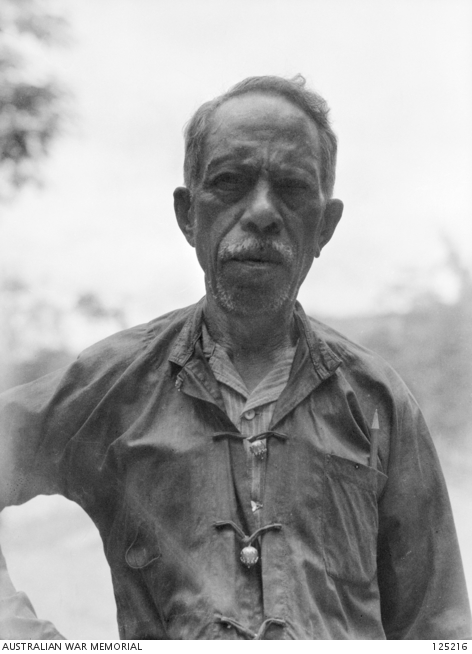

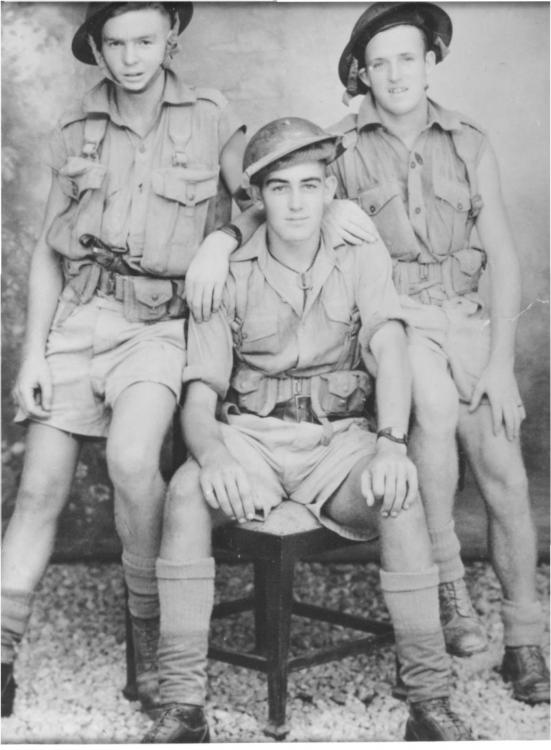

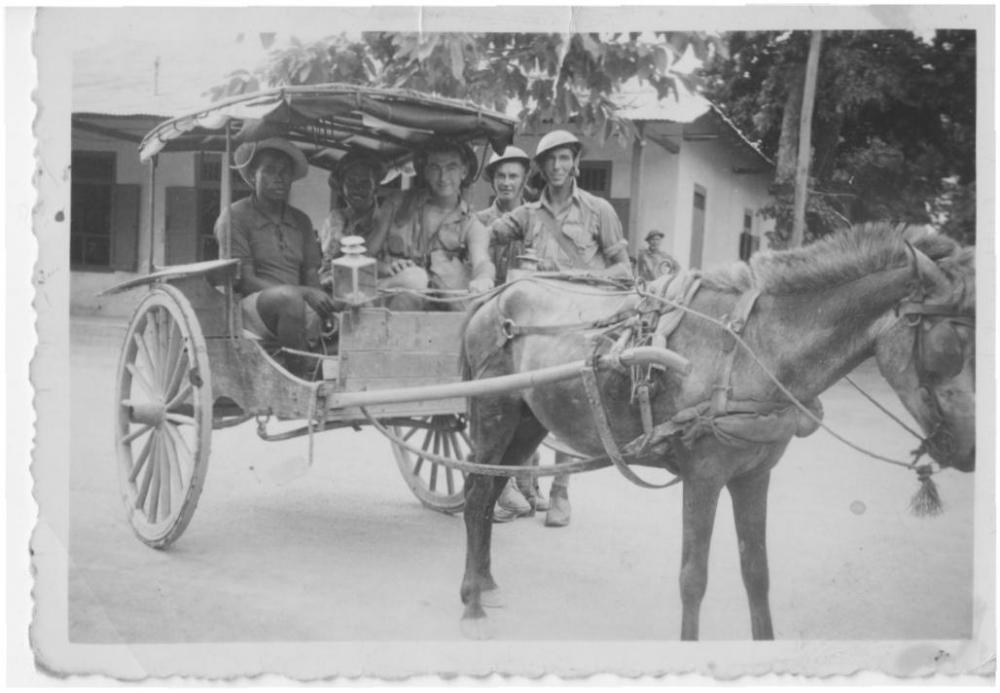

CHRISTMAS DAY IN DILI 25 DECEMBER 1941 INTRODUCTION The fullest (and frankest) account of how the men of the 2nd Independent Company spent Christmas Day 1941 in Dili is provided by Cyril Ayris in ‘All the Bull’s men’ (pp.71-74). Annotation on rear of photo: Timor-Dilli Chinese Studio Xmas 1941: Colin Criddle – Pinky L, Fred Smith – Smithy C, Cyril Doyle – Tiger R - [Source: 2/2 Commando Association of Australia photo archive] One photo located in the Association archives was taken on Christmas Day 1941 in Dili. It is a remarkably evocative informal group portrait of three men from No. 2 Section: Colin (Pinky) Criddle, Fred Smith, and Cyril (Tiger) Doyle; they distinguished themselves in the defence of the airfield when the Japanese landed nearly two months later on February 19 1942. 2nd Independent Company men on leave in Dili – January 1942 – Tony Adams tentatively identified on the right – [Source: 2/2 Commando Association of Australia photo archive] The men of the Signals Section also spent the day together and Corporal Harry Wray recorded his memories of it and related events and personalities. HOW THE SIGNALS SECTION SPENT CHRISTMAS DAY IN DILI, 1941 [1] For the first few days at the Dili aerodrome my Section was camped in a lean to shed of palm thatch, about six feet high in front and three feet high at the back. The mosquitos were very thick at night and we slept under nets, all snowy white, and could be seen for hundreds of yards at night. The Dutch had green nets, and green tents, all our equipment shone with new whiteness, and was difficult to camouflage. Photo included in 'Report on a visit to Portuguese Timor' by Captain Johnston, Dr. Bradfield and Mr. Ross - 29th December, 1940 - 1st January 1941 (NAA: A816, 19/301/778) Later we shifted to a coconut grove skirting the aerodrome and pitched tents there. The ground was very wet, almost boggy in fact, and even with ground sheets under our sleeping bags became damp.On Christmas Day, we were allowed leave to visit Dili in the afternoon, and several of us hired a tiny carriage drawn by two Timor ponies and set off in state. We had a look at the cathedral, and a walk around the town, which did not take long. Portuguese postcard showing the Dili Cathedral We bought soap and Chinese cigarettes from some of the numerous Chinese shops, then went to the waterfront and had a look at the small Jap ship tied up at the jetty. This ship used to lie off Dili prior to our arrival and before the Jap entry into the war, and every day would go out beyond the three-mile limit and send and receive messages from Japan on the very powerful wireless set, which had been installed on board. After the Japs came into the war our Hudson’s based at Koepang heard of the ship and how it went out each day to send and receive messages, so one day a Hudson swooped down and machine gunned it to such an effect that most of the crew jumped overboard, and the crew of the Hudson had the pleasure of seeing sharks put an end to those who did so. The remainder of the crew took cover and let the ship run as she pleased until she piled up on the beach of a nearby island. Later a Dutch ship found her deserted and towed her back to Dili where the Dutch almost tore her apart searching for what they could find. When I saw her the panelling was ripped off walls, bedding ripped open, and everything in a terrible mess after the search. Goodness knows if anything worth having was found. We managed to get a few batteries from the radio installation, which came in very useful later on. A fair number of drums of oil and petrol were found in the holds of the ship; however, the Japs had put sand in the oil and petrol before leaving her derelict. After filtering, some of the oil and petrol came in quite handy to the Dutch, and us also. The Japs had also taken the precaution of removing a few vital parts from the engine, which made it hopeless to attempt to get the engine running. I noticed that the Hudson had made a good job of the doing over, which it gave the ship, as the bridge and decks were holed like the top of a pepper pot. Patricio Luz, a radio operator at the Portuguese radio station prior to the occupation. Behind him is the wreckage of the Japanese ship, ‘Nanyei Maru’, in Dili harbour. It had been bombed and strafed by the RAAF immediately after the declaration of war with Japan and after drifting unmanned was eventually towed to Dili harbour. (Photographer Sgt K. Davis). Source: AWM photo ID number 121402: Dili, Portuguese Timor 1945-12-09. After visiting the Jap ship, we went back to the town square near the cathedral and hired a couple of the carriages to take us back to the aerodrome. The drivers at once whipped at their horses and off we went at a gallop. Our ponies managed to take the lead, and one of our chaps in the other carriage thinking he could make a better job of the driving took the reins from the native boy, and with whip and shouts urged the ponies on to greater efforts. This resulted in his carriage gaining on us, and in trying to pass he took his carriage too near the edge of the drain running alongside the road. This drain was about twelve feet deep and about twelve feet wide. Jerry’s carriage hung balanced on the edge of the drain while the ponies hung down the sides. We ran back to the rescue and soon dragged the terrified little ponies back onto the road and righted the carriage. Jerry had to pacify the boy with an extra Pataka (1/8). Annotation on rear of photo: Taken January 1942 – One of the carts used to a great extent – L to R – M. Ryan, F. Smith, A. Dalbridge. Source: 2/2 Commando Association of Australia photo archive. All hands were supposed to take quinine twice a day. This quinine was in powder form, and it was very difficult to persuade anyone to take it, and I imagine this contributed to the heavy toll malaria was soon to take. I had the job of seeing that my Section had his quinine, and watched to see that everyone did take it, but I used to wrap each dose in a cigarette paper, and consequently did not have much trouble getting everyone to have his dose. One man who preferred the powder neat, and said he liked it: a peculiar taste. The only other time I was in Dili was one morning when we had a few hours leave. One of our officers said he would take a few of us who had happened to run into him in the street, to dinner at one of the few hotels. [2] On the way, there he told me that he was short of money and perhaps I could lend him some. I did and had the pleasure of him standing us all drinks and dinner at my own expense, as I only recovered a very small part of the loan a few days later. Source: Hudson Fysh ‘Australia’s unknown neighbour – Portuguese Timor’ Walkabout, vol. 7, no.7, May 1st 1941, p.7. At this hotel, we met a man who was an employee of Imperial Shell and had been making a survey of Timor for the purpose of assessing the geological possibilities as regards oil. [3] This chap told us an amusing tale, or rather an amusing experience. Not long before the Jap declaration of war, such as it was, the Japs had concluded a treaty with the Portuguese by which they were given full rights to the use of Dili aerodrome, for civil purposes of course, or what they told the Portuguese at the time. On the day that this treaty was finalised the Shell man happened to be in Dili staying at the hotel. Later in the day a Qantas flying boat pilot came along to the hotel for the night. The flying boats stayed overnight at Dili at that time. The pilot and the Shell man were old friends. The pilot asked the Shell man to accompany him to a function that evening to celebrate the treaty between the Japs and the Portos. The Shell man was finally persuaded, and the pilot obtained the necessary invitation for his friend. Mr George Bryant, an Australian who has lived in the area for the past 24 years, being welcomed aboard the RAN vessel HMAS ‘Warrnambool’, a section of Timforce, which has arrived in the area to ensure that the Japanese forces carry out the surrender terms. Source: AWM phot ID number 117047: Dili, Portuguese Timor, 1945-09-23. The Shell man told us it was a terrific celebration, with both the Japs and the Portos getting more and more drunk as time went on. Everyone was on the best of terms with everyone else, the Japs sang songs in praise and honour of their Porto friends, and the Portos did likewise, but the cream of the piece came when the Japs and Portos decided to honour their English and Australian friends by roaring out ‘God save the King’ in the heartiest fashion. Only a few weeks after this token of their everlasting friendship, they were at war with us. I do not know what became of the Shell man, as several Qantas flying boats called after I saw him, and before the Japs appeared on the scene. He may have left safely, and in time. There was an old man living in Dili, an Australian who had been there for years. He did a little prospecting at times, but latterly I think he was living at the Australian Consul’s house doing odd jobs there. As it happened, he was the uncle of one of our men, quite a coincidence that they should meet in Dili of all places. I do not know what became of this man, he was in Dili during the Jap occupation I believe and may still be there. [4] I forgot to say that our Lieutenant [John Rose] managed to buy a bundle of fresh fish something like herrings in appearance, and full of bones, for our Christmas dinner. We also provided a few fowls, which we souvenired from a deserted house nearby. The owner of the house was an Arab, and we learned later a spy in the pay of the Japs. He kept well out of the way while we were at the aerodrome. We did hear subsequently bumped him off for some reason best known to themselves. They liquidated several of their friends at different times, as you will hear later, one of their very good friends just because he was unlucky enough for appearances to be against him. To get back to the Christmas dinner, the fowls gave us a terrific chase in the heat of the day, but we managed to catch about six of them, so with the fish did quite well for ourselves. NOTES [1] Corporal Arthur Henry Kilfield ‘Harry’ Wray (WX11485), Recollections of the 2nd Independent Company Campaign on Timor, 1941-42, manuscript in 2/2 Commando Association archives. [2] This was probably Lieutenant Colin Doig. [3] This was M.L.E.J. Brouwer, a Dutch geologist from Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij (Shell), arrived in Timor during April 1941. There was considerable suspicion that Brouwer was a Nazi sympathiser, but a later memo indicated that 'Brouwer is a geologist for cover only' suggesting that his primary role was not exploration. See Tim Charlton ‘History of petroleum exploration in Timor-Leste’ http://www.timcharlton.co.uk/other-projects/timor-leste-history-of-oil-exploration [4] Bernard Callinan described Bryant as David Ross’ ‘general factotum’. Bryant’s nephew was Cpl. Bryant, William Frederick VX29713, a cook in Q Section. Bryant was born in Melbourne in 1882 and had worked in Portuguese Timor for at least 28 years. Although ill, Bryant survived the war in Dili. For an interesting summary of Bryant’s life, see J. Carey ‘Link with the past’ 2/2 Commando Courier vol. 140, September 2002, pp.10-11 https://doublereds.org.au/couriers/2002/September/ Revised and adapted from an earlier post commemorating the 75th Anniversary of this event Ed Willis 23 December 2021

-

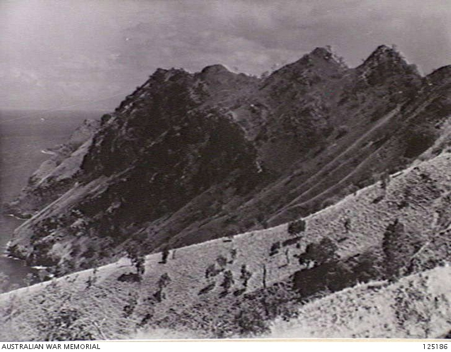

THE OCCUPATION OF DILI BY THE NO. 2 AUSTRALIAN INDEPENDENT COMPANY AND THE DUTCH CONTINGENT – PART 2 December 16-20, 1941 Paul Hasluck prepared a succinct and authoritative summary of the events leading up to the joint decision made by the Australian, British and Dutch governments to proceed with the occupation of Dili in neutral Portuguese Timor in mid-December 1941. [1-2] Hasluck’s summary of the Allied decision-making process and concomitant diplomatic negotiations with Portugal regarding this initiative is complemented by Lionel Wigmore’s brief narrative of the actual events. Both Hasluck’s and Wigmore’s contributions were prepared for the official history ‘Australia in the War of 1939-1945’. This post supplements an earlier contribution commemorating the 75th anniversary of this event from a more personal viewpoint; see: https://doublereds.org.au/forums/topic/89-75-years-on-the-australian-and-dutch-landings-at-dili-17-20-december-1941/#comment-135 Hasluck’s summation follows: THE ‘TIMOR PROBLEM’ Australia itself, adding to the measures previously taken for collaboration with the Netherlands East Indies and for the security of New Caledonia, had given further attention to the position of Portuguese Timor. Early in 1941 the Australian Government had become concerned at reports of Japanese activities in Portuguese Timor and particularly the way in which Japan was gaining support from the local population by arranging to purchase the exportable surplus of their coffee crop. As in the case of New Caledonia the first move by Australia was in the direction of giving commercial support to the Portuguese dependency. At the same time arrangements had been made to use Dili as an alternative stopping place on the Australia-Singapore civil air route and advantage was taken of this arrangement to appoint the Chief Flying Inspector of the Department of Civil Aviation, Mr David Ross, [3] as Australian Civil Aviation representative there. From the outset, however, it was indicated that Ross, who was furnished with light aircraft for his use, should also report to the Australian Government on the general situation in Portuguese Timor, both keeping an eye on what the Japanese were doing and also advising the Government on any opportunities which Australia could take to improve its position. The measures for the defence of Timor in the case of Japanese action against the Portuguese were also discussed in the course of conversations with the Dutch and the British in February 1941, and it had been agreed to have certain Australian troops available with Dutch troops at Koepang in Dutch Timor. Later in the year the possibility of a German move through Spain and Portugal caused the Department of External Affairs to draw attention to the possibility that, if control of the colony from Portugal were broken, Japan would probably seize the opportunity to take Timor under protective custody. The Government therefore approached the United Kingdom Government with a view to reaching an understanding between the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Australia regarding the occupation of Portuguese Timor, either jointly or by the separate forces of one of the three nations in the event of either German occupation of Portugal, a Japanese landing in Timor without the outbreak of war between Japan and the Allies, or, in the final extremity, in the case of war with Japan. [4] The United Kingdom agreed with the sense of the Australian proposals and also proposed discussions with Portugal. For the purpose of these discussions the United Kingdom asked Australia whether, if Portugal agreed to accept reinforcements, Australia would be willing to accept commitments in respect of Portuguese Timor in addition to the commitments already accepted in respect of Ambon and Koepang. By a War Cabinet decision of 15th October Australia agreed that Portugal should be asked whether she was ready to accept outside help if help should be found necessary by the military authorities on the spot, and that both the Netherlands and Portuguese Governments should be asked to agree to local discussions between Australian, Dutch and Portuguese military authorities regarding the necessary preventive measures. The War Cabinet also decided that, in view of the threat to Australia which would arise from a Japanese occupation of Timor, Australia should cooperate to the fullest practical extent in measures for the defence of the colony. To that end the Australian air forces to be provided for reinforcement of Ambon and Koepang should also be available for operations in Portuguese Timor and an additional battalion of supporting troops should be made available to reinforce Portuguese Timor if the Portuguese agreed to accept reinforcements. [5] At the suggestion of the United Kingdom, Ross was given rank as Australian Consul at Dili in order to facilitate his work. Negotiations with the Portuguese Government had not been concluded when war came. BRITISH NEGOTIATIONS WITH PORTUGAL As mentioned earlier, some 1,600 Australian troops had been sent to Dutch Timor from Darwin on 12th December. That day the Portuguese Government agreed to a proposal made by the British Government, with Australian and Dutch approval, that the Governor of Portuguese Timor should acquiesce in the arrival of Australian and Dutch forces in Portuguese Timor if it was attacked. The colony of Portuguese Timor, consisting mainly of the eastern half of Timor Island, only 400 miles from Darwin, had a population of 450,000 including only about 300 Europeans and being half a world away from a metropolitan state of limited economic and military resources was itself backward in development and practically undefended. Defensively it was the weakest point in the Indonesian chain and the point nearest to the Australian mainland. There had been signs of increasing Japanese interest in the colony for some years. The diplomatic weakness of the Portuguese arose both from the position of Portugal as a small Continental European state conscious of the dominating power of Nazi Germany on the Continent and from the fact that the most important of its Asiatic colonies, Macao, was under immediate threat from the Japanese army in South China. The Portuguese Government, under Dr Salazar, though holding to the current alliance with Great Britain, was susceptible to Axis pressure both in Europe and Asia. They had no love for the Japanese but were not strong enough to risk offence. THE DIE IS CAST On 16th December the British Government informed the Portuguese Government that a Japanese attack on Timor seemed imminent and it had arranged with the Australian Government that Dutch and Australian officers should see the Governor of Portuguese Timor and, in anticipation of an invitation to lend help, some 350 Dutch and Australia n troops would arrive two hours after the interview. [6] On the 17th the Australian Lieut-Colonel Leggatt [7] and the Dutch Lieut-Colonel Detiger, both in civilian clothes, arrived at Dili, the capital of the Portuguese colony, and were introduced to the Governor by Mr David Ross, the Australian Consul there. The Governor said that his instructions were to ask for help only after being attacked. He was told that troops were on their way. (Netherlands Indies troops numbering 260 and 155 Australians had embarked for Dili in a Dutch warship on the 16th). Meanwhile in Lisbon: Dr Salazar's reaction was sharp and violent. He refused to allow the Governor to agree to assistance except in the event of an attack. He argued that an earlier admission of Allied troops would mean the abandonment of Portuguese neutrality and would be followed by the Japanese seizure of Macao. [8] At Dili at 9.45 a.m. on the 17th the Governor told the Australian and Dutch envoys that he had received a message from Lisbon and wanted an hour to decode it. This was agreed to. The Dutch warship carrying the troops had already arrived. At 10.50 the Governor said that the message instructed him not to allow troops to land unless Portuguese Timor was attacked, and therefore his forces must resist. Leggatt and Detiger replied that they hoped there would be no fighting and pointed out that the defending force was too small to succeed. The Governor said that he would see the commander of his troops and, in the words of Leggatt's report, ‘ascertain what arrangements could be made’. That afternoon the troops landed unopposed. The inhabitants seemed friendly. The British Government, anxious to avoid a break with Portugal, proposed that the Allied forces should be withdrawn on the arrival of Portuguese reinforcements, and this was agreed to. On 31st December the Australian Advisory War Council was informed of a proposal to replace Dutch forces in Portuguese Timor with an equivalent number of Australian troops from those already in Dutch Timor. They were also informed of Japanese pressure on Portugal to secure withdrawal of Allied forces, under threat of Japanese action, and advised of the proposal that Australian and Dutch forces be withdrawn from Portuguese Timor on the arrival of 700 Portuguese troops. [9] The Australian Chiefs of Staff, however, in a report dated 4th January, expressed the view that 700 Portuguese would not constitute an adequate protection. It was decided to place this view before the British Government. By 22nd December the Australian force around Dili had been increased until it comprised a complete Independent Company. Soon it was learnt that the Portuguese reinforcements were not expected before the second week in March. On 20th February, however, Japanese forces landed in Dutch and Portuguese Timor. [10] By the 23rd the main Allied force in Dutch Timor had been overcome but the Independent Company fought on in the mountains where it was joined by a considerable number of men from Dutch Timor. [11] Lionel Wigmore continues the story of the occupation in a more narrative fashion: [12] DECISION MADE TO OCCUPY DILI Preceded by about 100 additional troops from Java, Colonel van Straaten arrived at Koepang by air on 15th December to command the Dutch forces on the island. He was to be under Leggatt's command. A conference held that evening was attended by the Dutch Resident at Koepang (Mr Niebouer); the Australian Consul at Dili, Mr Ross; van Straaten; Leggatt; Detiger; the Commander of the old 16-knot Dutch training cruiser Soerabaja (5,644 tons); the Officer Commanding the Australian air force squadron, Wing Commander Headlam; [13] the Commander of No.2 Australian Independent Company, Major Spence; [14] and staff officers. Van Straaten said he had been informed by the Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies, Jonkheer Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer, that as a result of negotiations between the United Kingdom, Dutch, Australian and Portuguese Governments it had been agreed that in case of aggression against Portuguese Timor by Japan, the Governor of Portuguese Timor would ask for help, and Australian and Netherlands East Indies troops would be sent there; further, that if the Government of the Netherlands Indies considered the matter urgent, and an attack on Dili was imminent, the Portuguese Governor would be informed and would ask for these troops to be sent. The colonel added that he was instructed by the Governor-General to say that Japanese ships were now in the vicinity of Portuguese Timor, and it was urgent that troops be sent to Dili. It was agreed that Leggatt and Detiger leave for Dili next day by the Canopus, [15] and convey this information to the Governor at 8 a.m. on 17th December. Ross flew back to Dili to arrange the interview. INDEPENDENT COMPANY AND DUTCH TROOPS TRANSPORTED TO DILI Netherlands Indies troops numbering 260, and 155 of the Independent Company embarked on the Soerabaja at 8 a.m. on 16th December, leaving the remainder of the Independent Company to follow aboard the Canopus on its return to Koepang. Wearing civilian clothes, Leggatt and Detiger were introduced by Ross to the Governor on the 17th, and Leggatt conveyed to him the message he had received through van Straaten. The Governor said that his instructions were definitely to ask for help only after Portuguese Timor was attacked. He was told that this would be too late; the troops were on their way and must land. He then asked that the matter be put in writing, and when this had been done, asked for half an hour to discuss the matter with his Ministers. At 9.45 a.m. he said a message had been received from Lisbon, and he wanted an hour to decode it. This was agreed to, but meanwhile the Soerabaja had arrived off Dili, escorted by Australian aircraft. At 10.50 a.m. the Governor announced that the message was to the effect that he definitely must not allow troops to land unless Portuguese Timor was attacked, and that therefore his forces must resist such a landing. Obviously, the Governor was seeking to follow a diplomatically ‘correct’ procedure which would avoid prejudice to Portugal's neutrality. The delegation, however, expressed the hope that there would be no fighting, pointing out that the Portuguese force was too small to succeed. The Governor said that when the landing occurred, he would see the commander of his troops, and ‘ascertain what arrangements could be made’. [16] Leggatt and Detiger then boarded the Soerabaja and reported the interview to van Straaten. DILI TOWN AND THE AIRFIELD OCCUPIED That afternoon the troops landed. Spence told his men that they might have to fight as soon as they stepped ashore; but they and 50 Dutch troops landed unopposed, on a sandy beach about two miles and a quarter west of Dili, in the early afternoon. A small party of signallers went into the town under Lieutenant Rose, [17] to take over the radio station and signal Sparrow Force at Koepang. They were agreeably surprised to find the inhabitants apparently friendly towards them, and to experience no difficulty in taking over the radio station. The Dutch were to occupy the town, and the Australians the airfield about a mile and a half west of it on the coast. As a precaution, the Australians took up positions near their objective, while Spence advanced with his No. 1 Section to the airfield and met the Governor, the Dutch Consul at Dili, and Ross. Australian occupation was agreed to by the Governor, though apparently with reluctance. Spence was unable to discover the whereabouts of the Portuguese troops, or their strength. The Australians then moved in, and at dusk were digging in around the two runways, and the hangars. The attitude of the Portuguese authorities continued to cause concern. Leggatt and Detiger returned to Koepang on 17th December, but Leggatt was back in Dili for a few hours on the 19th. He found that at van Straaten's request the Governor had sent most of the Portuguese force out of Dili, but that the Portuguese Council was meeting that day to discuss the situation brought about by the landing. Subsequent indications were interpreted as meaning that the Governor was definitely against the occupation, was obstructing by all means in his power, and probably would assist any Japanese attack. Leggatt reported to Australian headquarters that the pro-British Portuguese in Dili could form a government, with the support of the Allied force, and that Ross recommended that that support be given if the Governor persisted in his attitude. On 31st December a message was received by Sparrow Force to be passed to Ross that, owing to a severe Portuguese reaction and threats to break off diplomatic relations, British proposals had been submitted to Portugal with Australia's approval. These were that the Dutch force withdraw to Dutch Timor and be replaced by more Australians from Koepang. The message added that this might relieve the situation, as the Portuguese were highly antagonistic to the Dutch, and had presented a note amounting to an ultimatum. [18] Sparrow Force replied to the message from Australia that the arrangement whereby forces had to be maintained at Koepang and Dili meant that they were weak at both points. If the proposals were carried into effect Koepang would be further weakened. INDEPENDENT COMPANY DISPOSITIONS By 22nd December the remainder of the Independent Company, comprising a third platoon (Captain Laidlaw [19]) with signallers and engineers had reached Dili, and the company had received its only transport vehicles - two one-ton utilities and three motor-cycles. The Australians quickly set about obtaining a thorough knowledge of the country in which they might have to fight. [20] They formed friendships with the people of Dili so quickly that a picquet with transport had to be sent to the town to bring men back to their lines after the hospitality they enjoyed on Christmas Day. REFERENCES [1] Paul Hasluck. - The government and the people 1939-1941. – Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1952. (Australia in the War of 1939-1945, series 4 (Civil), v.1). See esp. Ch. 13 ‘Danger from Japan, July-December 1941’: 538-539. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1417319/538-539/ [2] Paul Hasluck. - The government and the people 1942-1945. – Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1970. (Australia in the War of 1939-1945, series 4 (Civil), v.2). See esp. Ch. 2 ‘The enemy at the gate, February-March 1942’: 100-102. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1417320 [3] Gp Capt D. Ross, RAAF. Aust Consul in Timor 1941-42; escaped from Japanese; joined guerrilla forces; Dir of Transportation and Movements RAAF to 1946. Of East Malvern, Vic; b. 15 Mar 1902-1984. [4] War Cabinet Minutes 1313, 13 Aug and 1333, 3 Sep 1941. [5] War Cabinet Minute 1410, 15 Oct 1941. War Cabinet Agendum 270/1941. [6] L. Woodward, British Foreign Policy in the Second World War (1962), p. 376, a volume in the official series, History of the Second World War. [7] Lt-Col Hon Sir William Leggatt, DSO, MC, ED. (1st AIF: Lt 60 Bn.) 2/22 Bn; CO 2/40 Bn 1941-42. MLA, Vic 1947-56. Barrister; of Mornington, Vic; b. Malekula Is, New Hebrides, 23 Dec 1894-1968. [8] Woodward, p. 376. [9] Advisory War Council Minute 639, 31 Dec 1941. [10] The Portuguese troops had left Lourenco Marques in a slow troopship on 28th January and were still on passage. They returned to East Africa. [11] Hasluck’s contribution, though written between 1952-1970 is still relevant and prescient. For a comprehensive up-to-date account and interpretation of these events, see, Bernard Collaery. - Oil under troubled water: Australia's Timor Sea intrigue. – Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2020. See esp. Ch. 2 ‘The Allies, Australia and Portuguese Timor’: 36-62. [12] Lionel Wigmore. - The Japanese thrust. - Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1957. (Australia in the war of 1939-1945, series 1 (Army), v.4). See esp. Ch. 21 ‘Resistance in Timor’: 466-495. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1417309 [13] Air Cdre F. Headlam, OBE. Comd No. 2 Sqn 1941-42; Comd various training schools 1942-44; Staff Officer Administrative HQ North-West Area 1945. Regular airman; of Hobart; b. Launceston, Tas, 15 Jul 1914-1976. [14] Lt-Col A. Spence, DSO, QX6455. OC 2/2 Indep Coy 1941-42; Comd Sparrow Force 1942; CO 2/9 Cav Cdo Regt 1944-45. Journalist; of Longreach, Qld; b. Bundaberg, Qld, 5 Feb 1906- 10 July 1983. [15] A steam yacht of 773 tons displacement, normally part of a civil force used in peacetime by the NEI government for customs and police duties, but in time of war attached to the navy. [16] Report by Lieut-Colonel Leggatt. [17] Capt J.A. Rose, NX65630. 2/2 Indep Coy; "Z" Special Unit. Salesman; of Manly, NSW; b. Wagga Wagga, NSW, 8 Jul 1920-1972. [18] Throughout the colonial history of Timor the Portuguese had mistrusted the Dutch, fearing that they would seek to annex their part of the island. Now they suspected that the Dutch would use the war as an excuse for doing so. [19] Maj G.G. Laidlaw, DSO, NX70537. 2/2 Indep Coy; 2/2 Cdo Sqn. Salesman; of Maryville, NSW; b. Gosford, NSW, 12 Dec 1910-1978. [20] The company's mapping work was so extensive that it enabled the Allied Geographical Section of South-West Pacific Area Headquarters, established later, to produce early in 1943 the most detailed map of Portuguese Timor that had been made. See ‘75 years on - exploring around Dili, December 1941-February 1942’ https://doublereds.org.au/forums/topic/91-75-years-on-exploring-around-dili-december-1941-february-1942/#comment-138

-

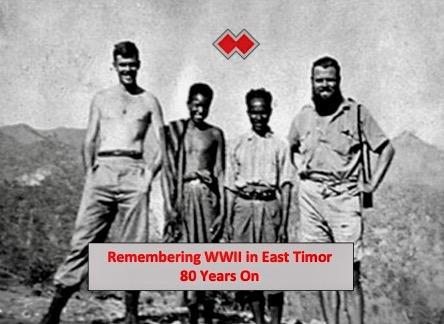

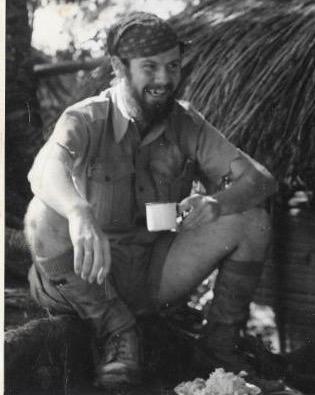

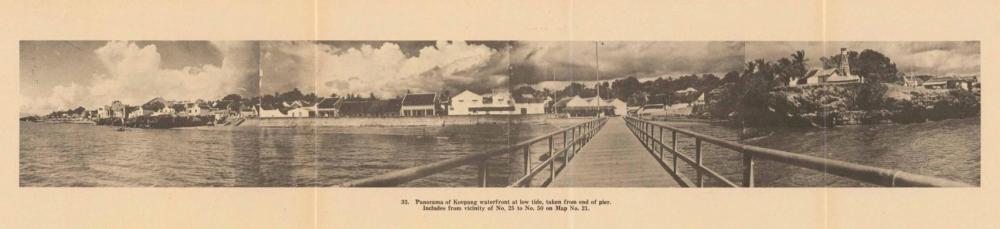

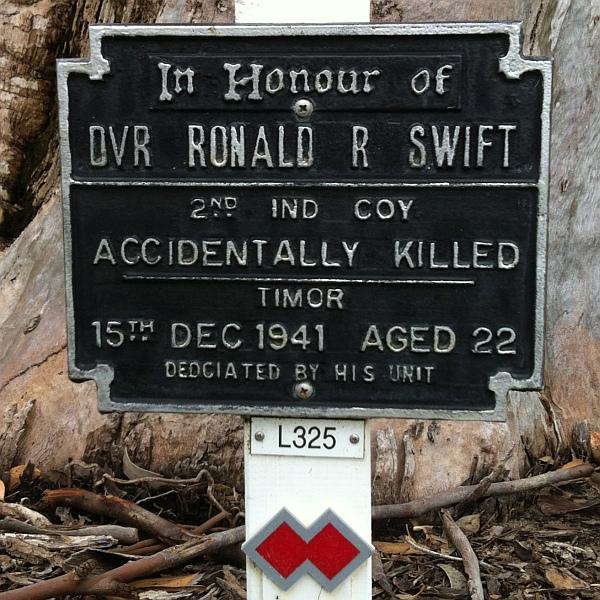

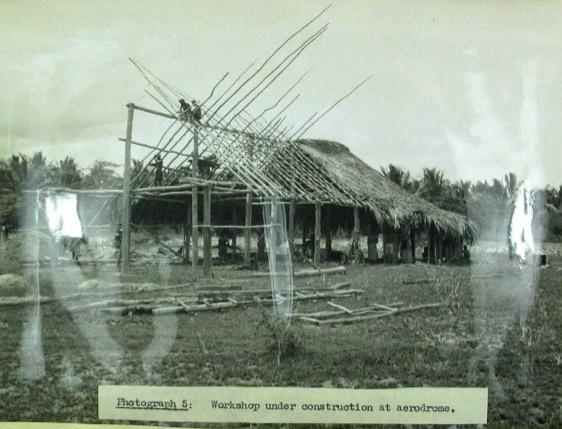

SPARROW FORCE DEPLOYS FROM DARWIN TO KOEPANG, DUTCH WEST TIMOR 8 – 15 December 1941 With the passage of 2021 and the transition to 2022 we move through the 80th anniversary years of significant events in the history of the Doublereds. December 10 2021 marks the 80th anniversary of the embarkation of the unit for Timor. Over the course of the new year we will post other stories marking significant events that occurred during 1942 during the 2nd Independent Company’s campaign on Timor. The following post utilises content from Cyril Ayris’s official history of the No. 2 Australian Independent Company (2/2nd Commando Squadron) All the Bull’s men. [1] DARWIN, MONDAY 8 DECEMBER 1941 When the 260-strong No. 2 Australian Independent Company (No. 2 AIC) arrived by train in Darwin at midday on Monday 8 December 1941, orders came through to board ship, their destination, as always, a mystery. Zealandia at sea [2] Their ‘troopship’ was the battered old coal steamer S.S. Zealandia, which, it could be conservatively stated, had seen better days. She had been around during World War I and had spent her last 25 years as a tramp steamer on the Australian coast. Other units to board the Zealandia were the 2/40th Battalion, the 2/1st Heavy Battery, 2/1st Searchlights, an L.A.D., a company of 2/11th Engineers and 2/1st Fortress Signals, all under the command of Colonel W.W. Leggatt, Commanding Officer of the 2/40th Battalion. The 2/40th was in an unhappy frame of mind. The men had been pushed from pillar to post in the Territory, while their numbers were continually depleted, supplying reinforcements to units already fighting overseas. To make matters worse they had been promised leave in the south and were waiting to board the Zealandia, which had been sent to Darwin to collect them. They had been looking forward to a leisurely cruise down the coast, followed by some leave in their home states when the order came to board ship – for somewhere overseas. …… Sergeant Bill Tomasetti said: ‘The embarkation was marked by some shameless pillaging of our stores by wharf labourers. It was brief because some No. 2 AIC personnel with a sense of justice, jumped down to the wharf and violently stopped it. We later heard that there had been a formal complaint over our intervention, however, there was no apparent follow-up’. Sergeant Bill Tomasetti [3] DARWIN, MIDNIGHT WEDNESDAY 10 DECEMBER 1941 It was about midnight, 10 December 1941, when the Zealandia finally slipped her moorings and turned her bows towards Beagle Gulf and the open sea. Most of the men lined the rails to watch the last Australian lights slide silently past until eventually there was nothing but the darkness, the ship’s creamy wake and the seagulls, wheeling and diving. It was a moment for reflection and perhaps a private prayer. Two escort ships took up positions on either side of the Zealandia – the Ballarat a corvette, and the Westralia a merchant cruiser which had been armed for her new role. Sunrise saw the little convoy clear the heads. At the same time a couple of Hudson aircraft appeared overhead to keep a watch out for enemy warships. It is a measure of the secrecy surrounding the formation of the independent companies that the commanding officer, Colonel Leggatt, had to ask Major Spence, on the Zealandia, precisely what the No. 2 AIC had been trained to do. He did not know its strength, what weapons the men carried or even what the company’s role was likely to be in the event of hostilities. It was after the No. 2 AIC’s special training had been explained, that the Colonel revealed they were going to Dutch Timor. He said their probable role would be to guard the aerodrome at Atamboea in the middle of the island. He explained that although the airfield had been rendered unsafe it could soon be repaired if captured by the enemy. The No. 2 AIC, with their expertise in stealth, booby traps and surprise raids, could keep the airfield unusable, unless the enemy committed a large force to its protection. The assembled officers were told that the group had been named Sparrow Force. They were given maps of Timor and reports on local conditions to study so that they could relay the information to their men. The reports revealed that rainfall on the island was best measured in metres rather than millimetres (it ranged from 490mm to 2950mm, depending on the location). The interior, it was noted, was populated by headhunters. The No. 2 AIC’s 60 Thompson sub-machine guns meanwhile had aroused so much interest, Lieutenant Tom Nisbet gave a talk on the weapon to the other officers. The men received the news that they were bound for Timor with mainly blank looks – only a handful knew where it was. The announcement that the Dutch would not allow the troops to bring Australian currency into the colony was also of academic interest as most were still broke. However, anybody who had any money had to hand it in for crediting in his pay book. The tropical heat turned the Zealandia into a floating furnace. The sun and the coal-fired boilers combined to create near-impossible conditions in the cabins and holds. Metal was too hot to touch and scarcely a breath of air reached below deck. A beer ration was announced but the grog was so warm it was almost undrinkable. More speed was required – the old ship could raise only seven knots. Volunteers were called to help the stokers shovel more coal into the boilers and, for once, there was a mini rush for the job. The reward was a beer which, the men were assured, would be cold. The three ships glided smoothly through the coppery sea, sending flying fish darting in silver flashes from the bows. The only sound was the steady thumping of the ship’s engines and the low chatter of the soldiers and crews. Signaller George ‘Happy’ Greenhalgh was one of the men who enjoyed standing near the bow. He recalled 60 years later: ‘We had never seen flying fish before. It was all so new to us, a great adventure. I remember the sea – it was like a millpond. You could stand on the bows and spit into the sea and you could see your spit land in the water’. Ray Parry: ‘We could see the seabed and odd patches of seaweed. The extreme heat and high humidity made conditions close to unbearable’. It was difficult to imagine amid such serenity that in other parts of the world nations were tearing themselves apart in mortal combat. It was even more difficult to imagine the tumult overflowing into these quiet waters. KOEPANG, DUTCH WEST TIMOR, AFTERNOON FRIDAY 12 DECEMBER 1941 On the afternoon of the second day, 12 December 1941, a faint smudge appeared on the horizon which slowly materialised into the island of Timor. As the Zealandia approached Koepang, a Dutch destroyer swept up alongside and took over escort duties from the Ballarat. (The Westralia had sailed ahead and was already in Koepang with a battery of 2/1st Australian Heavy Regiment). The Sparrow Force that landed in Koepang comprised 70 officers and 1330 men. The resident Netherlands East Indies garrison was about 500-strong. The Zealandia and her new escort slid through the channel between the small island of Roti and Timor, before turning north towards Koepang Bay. The men stared in dismay at the height and ruggedness of Timor’s mountains; those of Wilsons Promontory seemed tame by comparison. Koepang was like many north Australian harbours – shallow with big tidal variations. The Zealandia dropped anchor in the bay, leaving about 150 metres of mud between the ship and a causeway protruding across ugly brown coral. The shore was flat and palm fringed, but beyond the palms were low-lying hills which gave way to the distant mountains etched in rugged silhouette against a blue sky. From the sea there was nothing attractive about the place – and the brief glimpse of Koepang’s scattering of off-white buildings did nothing to improve first impressions. The unmistakably tropical smell of decay and cloying humidity, combined with the grotesque, betel nut grins of the ship’s new lumpers, left nobody in doubt that they had entered a new world; a world foreign to their own, a mere 600 kilometres over the horizon. Panorama of Koepang waterfront at low tide, taken from end of pier [4] Lighters pulled alongside swarming with Celebes boys who were much favoured by shipping companies because of their almost superhuman strength. They were a happy, laughing people, varying in colour from brown to black. Their short, slightly built stature belied their physical strength. The men climbed down the ship’s side on ropes and waded ashore through the shallows. Any hopes of a cold beer and some relaxation in Koepang were dashed when they were formed into ranks to march to their camp on an airfield at Penfoei. The situation on the waterfront was chaotic – there was no transport and no facilities for handling the big volume of stores and supplies that had to be transferred to the aerodrome. Callinan was given a lift to the airfield to inspect the camp site. At first glance he was agreeably surprised – it had been established on a hill of coral rock and was enclosed by a three-metre, barbed wire fence. It was a busy scene, home to a thousand men. Teams of 10 or 20 women, working under the direction of generally less energetic men, were hurrying everywhere with building materials in four-gallon petrol tins, suspended from bamboo poles across their shoulders. Their loads were in excess of 35 kilograms, yet they flitted barefoot over the rocky ground like swarming ants. Huts with cement floors and palm stem walls supporting thatched roofs had already been built for men and stores. There were even iron bedsteads, one for every man. And there were showers ...... and toilets. The drainage for these last two luxuries was not yet complete but work was progressing. Callinan’s spirits lifted at the sight of all this activity – then a Dutch adjutant broke the news that as the Australians were expected to go to Atamboea almost immediately, and as the camp was still under construction, they had been allocated an area outside the eastern fence. Tents would be supplied. The area proved to be a stretch of broken ground that had recently been excavated for its gravel. It was littered with refuse and in the middle was the locals’ latrine. It was mid-afternoon when the troops shouldered their weapons and struck off along the causeway through the coastal fringe of palms and scrub to their new home. Describing the campsite, Harry Sproxton said: ‘It looked like a limestone quarry. The ground was so hard we couldn’t get a tent peg in’. By nightfall tents were erected and water was boiling on a campfire. ….. The 2/2nd’s camp guard during that first night in Timor was extremely efficient, which was not well received by several officers and NCOs from other units who were challenged and made to say the password. A number of officers took offence at this perceived impertinence, but the guards stood their ground. PENFOEI, DUTCH WEST TIMOR, MONDAY 15 DECEMBER 1941 The No. 2 AIC suffered its first casualty on 15 December 1941, soon after its arrival at Koepang, when Lieutenant Doig accidentally shot and killed Private R.R. Swift, a driver. Doig was immediately suspended from duty and his commission was held in abeyance pending a court of inquiry. The court was never convened – the company was overtaken by events and the inquiry was put on hold, eventually to be forgotten. Company records … note: ‘December 15 1715 hours. Driver Swift VX33731 was accidentally shot with a .45 pistol and died approximately 15 minutes later on way to hospital. Swift was given a military funeral with B Platoon forming the guard of honour’. Driver Ronald R. Swift memorial plaque, Lovekin Drive, Kings Park Colonel Leggatt quickly realised that he had nothing like the strength needed to defend an island the size of Timor from enemy attack. He twice requested that an officer be dispatched to the island to make an independent inspection. Both requests were ignored. There had also arrived in Koepang about a 100 Dutch troops from Java under the command of Colonel van Straaten. On the evening of 15 December 1941, the day van Straaten arrived, a meeting was convened between the Dutch Resident at Koepang, Mr Niebouer; the former Department of Civil Aviation officer, now British Consul in Dili, Portuguese Timor, David Ross; Colonel Leggatt; Colonel van Straaten; the Dutch Territorial Commander, Lieutenant Colonel Detiger; the senior RAAF officer, Wing Commander Headlam; Major Spence and a number of other officers. The meeting was called to discuss the Japanese advance and the danger of neutral Portuguese Timor falling into their hands. Van Straaten said he had been instructed by his (Dutch) government to inform them that, if the Japanese arrived off Portuguese Timor, the Governor of Portuguese Timor, Manuel d’Abreu Ferreira de Carvelho, would ask for their help. He said that the British, Dutch, Australian and Portuguese governments had agreed that, in such an eventuality, Australian and Netherlands East Indies troops would be dispatched to resist any Japanese invasion. He then dropped his bombshell. Japanese ships had been seen in the area, he said, and it was urgent that troops be immediately dispatched to Dili. The instructions were that Colonels Leggatt and Detiger were to leave the following day, on the steam yacht Canopus, and inform the governor, at 8 a.m. on 17 December, that an allied occupying force was on its way to take over the task of protecting the colony. David Ross was instructed to fly to Dili ahead of them and arrange the meeting. The Netherlands troops and the majority of the No. 2 AIC were to sail at 8 a.m. on 16 December. The rest would follow on the Canopus when she returned from Dili. The ramifications of these orders were explosive, both politically and militarily. In essence, Australian troops would be landing in neutral Portuguese territory, hoping to be welcomed by the incumbent Portuguese, who had a garrison of about 500 mainly Timorese troops, with Portuguese officers and non-commissioned officers. These occupying forces were armed only with six Vickers machine guns … and some early-model Winchester rifles. The bottom line was that if the Portuguese resisted, the Australians would have to take Dili … by force. Australia, it was argued, could hardly stand idly by while the Japanese occupied half an island that was within bombing range of Darwin. …… the die was about to be cast. REFERENCES [1] Ayris, Cyril. - All the Bull's men: No. 2 Australian Independent Company (2/2nd Commando Squadron). - [Perth, W.A.]: 2/2nd Commando Association, 2006: Chapter 3 ‘Invasion’ pp.50-55. [2] Starboard side view of the merchant vessel SS Zealandia. Zealandia was sunk on 1942-02-19 during a Japanese air raid on the Darwin area. (Also, formerly P0444/214/214 and P00444.214) [3] Australian guerrillas in Timor. Sgt. W. Tomasetti (Melbourne) and Sgt. J. Garland (N.S.W. (negative by Parer). https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C33194 [4] Area study of Dutch Timor, Netherlands East Indies / Allied Geographical Section, South West Pacific Area. - [Brisbane]: The Section, 1943. – (Terrain study; no. 70) https://repository.monash.edu/items/show/26287#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0

-

Hi Tanya: Thank you for making contact -- please see post on the 2/2 Commando Association's Facebook page about Harry: https://www.facebook.com/2nd2nddoublereds Regards Ed Willis, President

-

Thanks Trevor for the reminder about the excellent "Australians At War Film Archive" -- https://australiansatwarfilmarchive.unsw.edu.au

-

Thank you for making contact Robert and letting the Association know about your Timor campaign film project. The video including the interviews with Tom Forster, Ray Aitken, John Burridge, Ray Parry and ‘Doc’ Wheatley is very interesting and will make a valuable addition to our video and image gallery on the Doublereds website. The post WWII fate of the criados was of considerable interest to the veterans of the 2/2 and 2/4 several of whom visited Timor and attempted to locate the young men who had campaigned with them including Paddy Kenneally, Ray Aitken, John Burridge, Arch Campbell and others. References to these activities can be found in the Ayris book and Arch Campbell’s book that can also be purchased and downloaded as an e-book from the Doublereds store (https://doublereds.org.au/store/). Please contact me directly by e-mail at: president@doublereds.org.au and I can refer you to other sources of information that are relevant to your project and also to discuss your request to film the forthcoming 2/2 commemoration ceremony at Kings Park on November 21. Ed Willis President, 2/2 Commando Association of Australia

-

Older members and supporters of the Doublereds may remember a small publication entitled ‘The Independents’ that was written by an original member of the No. 2 Independent Company - James (Jim) Palliser Smailes (WX12381). This is an epic poem written in bush doggerel verse that recounts the exploits of the unit during the Timor campaign. The Association has made available this unique publication for download as a digital book from its online store at a cost of $10 (https://doublereds.org.au/store/product/21-jim-smailes-the-independents-pdf/) and encourages all those with an interest in the campaign and don’t have to access to a copy to make a purchase – please spread the word about its availability to friends and family. The funds raised from the purchase of the book will be used to support projects like those to be delivered by Timor Leste Vision and Palms Australia that the Association provided grants to earlier this year. Smailes recalled: About three quarters of this whole poem was written on small scraps of paper as we moved about the island, and I used to leave it with different people for safety when in danger. Dr. Dunkley offered to carry it in his medical panniers because he was usually in a safe area. This I did, but his party were ambushed one day, and everything was lost. Upon arrival in the Northern Territory, I rewrote it on 20 pages of Salvation Army writing paper while at Larrimah. This was in the neck of my kitbag, and while passing through Mt Isa in Queensland it was stolen out of my tent. During our three weeks leave back in W.A. I wrote it all again from memory, and it lay in a drawer for many years. During the 1950s it was put into book form and sold for two shillings (20 cent) per copy and raised some hundreds of pounds to help finance and reticulate a special lawn area and some 40 trees, as a memorial to the 40 odd men who gave their lives in the Unit's three campaigns in the Pacific War. Now that I have come to write the story of Timor after all these years, it is most interesting how accurate the poetic version of the story is. That is not really surprising when it is considered that the verses were written within days or hours of an event taking place, when names places and figures were so vivid in one’s mind. Paper was very short and hard to find, some was written on a tobacco tin label, some on the back of old letters. The following small sample from ‘The Independents’ recounting the evacuation of the wounded and senior officers from Timor by Catalina that was featured in our previous post: From now on things were not so bad, our folks were all advised, That we were safe and fairly well, least those who had survived. A seaplane came across one night and took our wounded men, And all the surplus pips and crowns from down the Koepang end, The Brig. and all his retinue had joined our little band, (Brigadier Veal) But caught the first chance home again, this place they could not stand An interesting feature of the publication are the line drawn illustrations prepared by the legendary cartoonist Paul Rigby – some examples of which are included with this post.

-

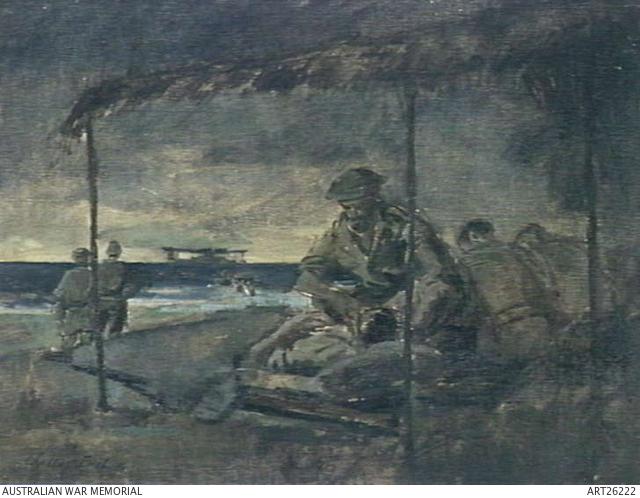

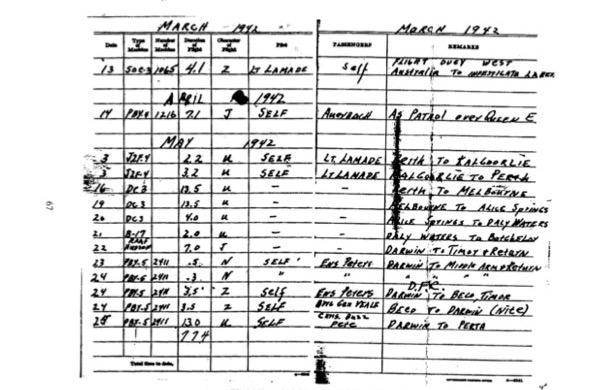

Consolidated PBY Catalina amphibious aircraft on display at the Aviation Heritage Museum, Bull Creek, Western Australia Rai-Mean is 35 miles (56 km.) from Aileu at a bearing of 198° and in the southwest corner of the province; suitable anchorage for small vessels. Good tracks run to Suai, Cumnassa and Beco. Cumnassa has possibilities for air strips. This town was shown on the Asia Co. map 5 miles (8 km.) west of its true position. Rai-Mean: Approximately 6 miles (9 1/2 km.) east of the mouth of the Lono-Mea River (not as shown on map). The anchorage is not very good. The surf is sometimes very heavy and rough and there is no shelter in the southeast season. It was found necessary during April to desist from landing stores and return to Suai, which is more sheltered. Track 26 - Beco to Rai-Mean: This track is subject to tidal rivers which would cause delay to all classes of traffic. Rai-Mean is approximately 2 hours journey north from the beach and the track passes through thickly timbered country; swampy in wet weather. It is situated on the flat coastal belt between the mountains and the sea which varies in depth approximately 5 to 12 miles (8 to 19 km.). [1] During mid-May 1942 there had been quite a deal of activity at Sparrow Force HQ. From Australia a message had come that Brigadier Veale was to return to the mainland for a conference and also that one Dutch officer was to accompany him. It was decided that this officer would be Lieutenant-Colonel van Straaten. It was also decided that Major Spence would take command of [Sparrow] Force HQ so on 20 May he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and shifted down to Mape. From Australia it was also advised that a Catalina would be making a flight into Portuguese Timor to evacuate wounded and sick personnel and the Australian and Dutch Officers. Captain Dunkley was notified of this evacuation and leaving Ainaro with four or five of his worst patients he travelled to Mape where he collected three more men who had been on their way to the hospital. On 21 May, Force was informed that the evacuations to take place at Suai on the south coast, so the doctor took the sick and wounded men down there to wait for the plane. However, on 22 May twenty two it was advised from Norforce that the plane would not be landing at Suai but at Rai-Mean the next anchorage along the coast towards Betano. Captain Dunkley could be given only one day’s notice of this change and had to then move his patients to the new evacuation point. He left on the morning of 23 May and commenced the trek along the coast, only to find that one of the many unnamed rivers running down to the coast was swollen from the recent heavy rains and was absolutely impassable. The party was forced to remain that night on the wrong side of the river with the knowledge that the plane was due in and would not be able to wait for any length of time, certainly not overnight. However, about 10 p.m. word was passed through to Captain Dunkley by native runner that the arrival of the plane had been put back a day and would not arrive until the following night the 24 May. Route followed by Captain Dunkley and party to Rai-Mean The next day the river was down sufficiently to allow the party to cross and move on down the coast to the village of Rai-Mean. They stayed in the village only a couple of hours before proceeding down to the beach where the plane was to come in. On the fading light of day the Catalina winged across the bay and touched down on the water. Stores were unloaded onto rubber rafts which had been brought over from Darwin and the sick and wounded, Lance Corporal P.G. Maley, Privates E.H. Craghill, A.A. Hollow, C.D. Varian, H.R.C. Cullen and K. Hayes went on board with Brigadier Veale and Lieutenant-Colonel van Straaten. Charles Bush - Depicting a scene of the evacuation of the wounded by Catalina from Rai Mean, Timor [2] The Catalina took only two hours to unload and load then took off and headed for Australia, leaving behind it the first mail the troops had received for some months. [3] Lieutenant Thomas H. Moorer, US Navy The pilot of the Catalina was Lieutenant Thomas H. Moorer of the US Navy. Moorer’s prior battle experience probably explains why he was personally selected by General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Allied Commander Southwest Pacific Area, to undertake this hazardous mission: [On the 20 February 1942] one of the Darwin-based U.S. Navy Catalinas, commanded by the C.O. of Patrol Wing 22, Lieutenant Thomas Moorer, had the misfortune to cross the path of the incoming air fleet just north of Bathurst Island. Attacked by nine Zeros, the plane crash-landed on the water in flames. The crew escaped in their inflatable dinghy and were soon picked up by Florence D, one of two Filipino-manned ships in the vicinity. The other was Don Isidro; and both were blockade-runners, loaded with supplies for MacArthur’s men on Corregidor. [Both ships had been] sent off … by a circuitous route, to avoid Japanese-held territory, that passed just north of Melville Island - and they, like Moorer’s Catalina, had the bad luck to be directly in the path of the carrier-based Darwin attack force. …. The [Japanese] Hiryu squadron saw Florence D, bombed and sank her. For the second time that day, Moorer and his men found themselves in the water. All but one of the flying boat crew lived to get ashore on Bathurst Island, with 40 survivors from the ship. Some walked across the island to the Catholic mission. Most, with the crew of Florence D, were picked up during the next three days by the rescue corvette H.M.A.S. Warrnambool. [4] After that harrowing experience, Moorer and his crew enjoyed a quieter time flying reconnaissance missions from the Catalina base that had been established at Pelican Point on the Swan River in Perth. Moorer wrote to Archie Campbell in December 1992 and gave him an account of his role in the Timor rescue mission: This is an extract from my Flight Log for May 1942. Note that I flew from Perth to Melbourne to see General MacArthur on May 16, then from Melbourne to Darwin, Alice Springs and Daly Waters on May 19, 20 and 21, I then went by car from Batchelor to Darwin Harbour to join my plane crew and support ship. On May 22, I took a seven hour flight in a RAAF Hudson to the Beco, Timor area to examine the coast line and select my landing spot. On May 23 and 24 I took short flights simply to check out my plane and familiarise myself with the Darwin area. On the night of May 24 I made the rescue flight to the Timor coast near Beco [Rai Mean], returning to Darwin precisely at midnight. All the six men were in bad shape and my crew had some difficulty loading them aboard. I remained at the aircraft controls in case a Japanese patrol boat showed up. I never did get a good look at all of my passengers and that explains why I could not remember exactly how many we rescued. I did remember Brigadier Veale. I returned to Perth on May 25, having gone full circle - flight time 64.3 hours. [5] Flight log of Lieutenant Thomas H. Moorer [6] Moorer served in several other demanding roles during WWII and then progressed a distinguished and decorated career in the US Navy for the remainder of his working life, retiring in July 1974 as a full Admiral and Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff. [7] [8] REFERENCES [1] Area study of Portuguese Timor / Allied Geographical Section, South West Pacific Area. - [Brisbane] : The Section, 1943. – (Terrain study (Allied Forces. South West Pacific Area. Allied Geographical Section) ; no. 50.): 16, 46, 82. https://repository.monash.edu/items/show/26455#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0 [2] https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C174949 [3] [Timor (1941-1942) - (Sparrow Force and Lancer Force) - Operations:] The Campaign in Portuguese Timor, A narrative of No 2 Independent Company. (Story prepared by Cpl SA Robinson) (No 5 Military History Field Team) - AWM54 [not digitised]: 50-51. [4] Alan Powell. - The shadow's edge : Australia's northern war. - Rev. ed. - Darwin, N.T. : Charles Darwin University Press, 2007: 91-92; see also Tom Lewis and Peter Ingman. – Carrier attack Darwin 1942: the complete guide to Australia’s own Pearl Harbour. – Kent Town, S.A.: Avonmore Books, 2013: 96, 121-122, 224, 226-228. [5] Archie Campbell ‘Sequel to Admiral Tom Moorer's query in October Courier’ 2/2 Commando CourierDecember 1992: 10; see also Archie Campbell ‘Where are the Sparrow 20? Appeal from Admiral Thomas Moorer’ 2/2 Commando Courier October 1992: 15. [6] Archie Campbell. - The Double Reds of Timor. - Swanbourne, W.A. : John Burridge Military Antiques, c1995: 67. [7] ‘From Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima: the World War II experience of Admiral Thomas H. Moorer’ American Valor Quarterly Autumn 2008: 4-8. https://view.joomag.com/american-valor-quarterly-issue-4-autumn-2008/0040648001422301760; see also Greg Tyerman ‘The life and times of Admiral Thomas Moorer’ 2/2 Commando Courier September 2004: 13-17. [8] Archie Campbell. - The Double Reds of Timor. - Swanbourne, W.A. : John Burridge Military Antiques, c1995: 68. Prepared by Ed Willis Revised 3 September 2021

-