-

Posts

619 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

News

Video & Audio

Men of the 2/2

Forums

Store

Gallery

Everything posted by Edward Willis

-

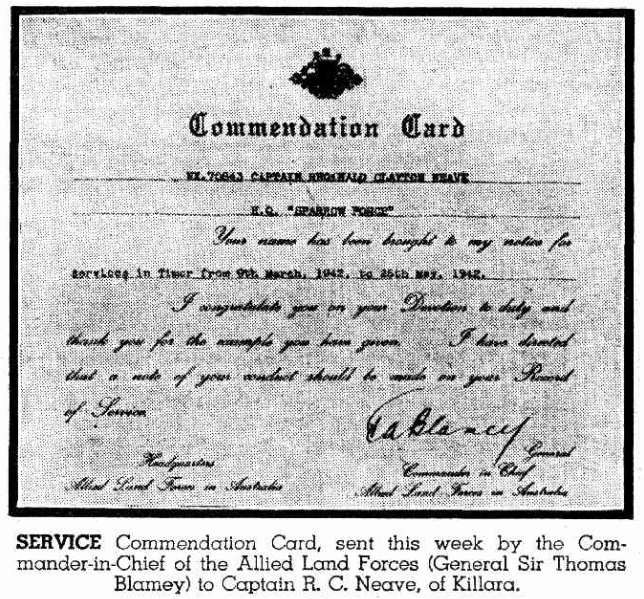

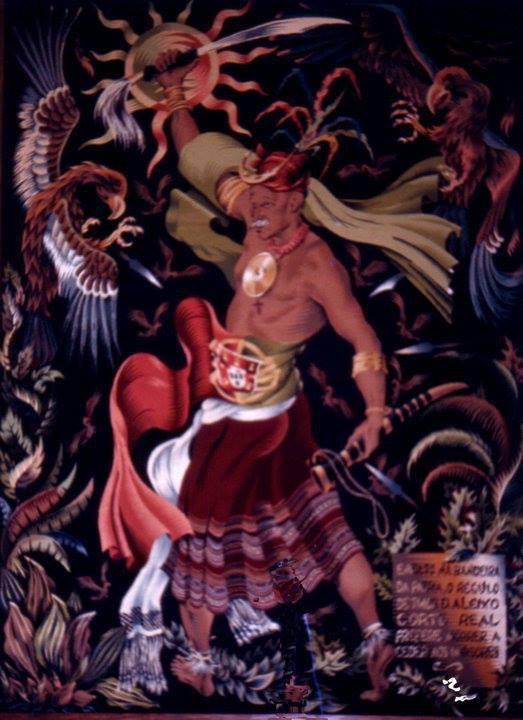

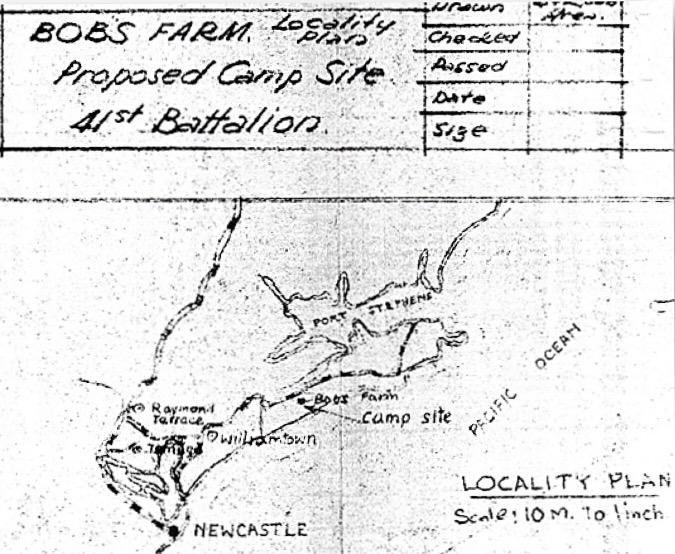

There is a Portuguese monument commemorating the people who lost their lives in the Zone of Concentration during WWII outside what is now the Fretilin headquarters in Liquiça. The inscription, dated 1970 refers to “Aos mártires da ocupação estrangeira” (martyrs of foreign occupation) and provides tangible evidence of another tragic aspect of the Japanese occupation years that has been largely forgotten. Monument to the Martyrs of Foreign Occupation In late October 1942, the Portuguese Governor reluctantly accepted the Japanese edict regarding ‘protective concentration’ and encouraged all Portuguese residents to move to ‘internment’ areas at Liquiçá, Maubara and the nearby hill village of Bazar Tete – this was deemed necessary for protection against the ‘rebeliões de indígenas (rebellious Timorese)’. Many Portuguese (and a few Timorese) took the opportunity to be evacuated to Australia at this time and were settled at Bob’s Farm Evacuation Camp that was the topic of our previous post. For those that remained, initially, the protection zone comprised the entire part of the coast stretching from Liquiçá to the mouth of the Lois River with people encouraged to gather in the towns of Liquiçá and Maubara. However, earlier on, several families stayed in the immediate vicinity where they were better able to cultivate subsistence crops. That situation changed quickly, with constant intimidation and confrontations with the ‘colunas negros’ (black columns). In May 1943, members of the Portuguese military detachment in Maubara were disarmed and demobilised. In the town, some internees still managed to maintain small vegetable gardens. Internees were permitted to access the fish farms at the Granja Eduardo Marques (at Boibau) and at the properties of the Sociedade Agrícola Pátria e Trabalho near Fatu-Bessi. Gradually, through more or less indirect pressure, the Japanese were also urging Timorese to stop selling their produce in weekly markets. Anxieties were further increased by sporadic Allied bombing and strafing attacks that sometimes caused Portuguese and Timorese casualties. In September 1944, without warning, the Japanese ordered the transfer of the approximately 200 people based in Maubara to Liquiçá, further undermining living conditions for the internees. Very late in WWII (early July 1945) for the internees were transferred to one of the properties of the Sociedade Agrícola Pátria e Trabalho in the Lebo-Men area, near Fatu-Bessi. Portuguese historian Jorge Silva Rocha recently published an authoritative account of the Zone of Concentration in the Liquiça-Maubara area that has been translated into English and made available to read here – very little has been published in English on this topic to date. PORTUGUESE PRISONERS IN TIMOR DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR Jorge Silva Rocha SOURCE: Jorge Silva Rocha ‘Prisioneiros Portugueses em Timor durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial’ [‘Portuguese prisoners in Timor during the Second World War’] in Prisioneiros de guerras: experiências de cativeiro no século XX / coordenação: Pedro Aires Oliveira. – Lisboa: Edições tinta‐da‐china, 2019: 223-245. As in other theatres of World War II, the war in Asia and the Pacific, more than a military confrontation between enemy armies, was above all a violent confrontation between different cultures and races. [1] A struggle between “white men” and “yellow men”, different in their physiognomy but also with different values and understandings about the respect deserved by the opposing forces imprisoned during combat, about mercy and also about restraint in actions. Bushido, the ancestral samurai code of conduct proudly followed over generations, continued to guide the action of Japanese combatants during World War II towards the correct execution of military tasks, irreproachable conduct in everyday life and, the pursuit of a dignified death in combat. However, the precepts of bushido that established that the combatant should always act with justice and compassion towards his enemy, defeated or weakened, were permanently ignored when dealing with his prisoners of war and civilian internees. In his understanding, the non-Japanese who allowed their capture in combat did not deserve any contemplation and should be hated, despised and killed. With total disregard for the Geneva Convention which established, from 1929, the right and obligation of prisoners of war to be treated humanely and without subjection to torture and any acts of physical or psychological pressure, guaranteeing them health aid and food, as well as respect for their religion, in the concentration and internment camps for prisoners of war established by the Japanese military forces during the war in the Pacific, violent and deadly beatings, refusal to provide medical aid, the insufficient supply of food and even medical experimentation on prisoners. In Japanese concentration and internment camps, thousands of prisoners died every day from diseases caused by malnutrition, such as beriberi and scurvy, or from tropical epidemic diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, dysentery, tropical ulcers, and so on. the cholera. Furthermore, any attempt to escape “white” prisoners was doomed to failure from the outset. His skin colour worked like a prisoner's uniform that it was not possible to take off. [2] Captive experiences in Japanese-occupied Asia varied enormously from region to region. While some prisoners of war, mostly Western soldiers, were sent to Japan and used as manual labour in forced labour, others were forced to work until exhaustion in the construction of the so-called «Death Railway» between Burma and Thailand. Civilian internees were, as a rule, gathered locally in often improvised camps, but this did not mean that they had an easier life than that of expatriate prisoners. They, too, ended up seeing their health irremediably undermined, their property expropriated or destroyed, and their means of subsistence stripped away. It is estimated that one in three “white” prisoners died at the hands of the Japanese. If in some concentration camps built by the Japanese military forces the mortality rates were below ten percent, there were others where the same rates reached values above 30 percent. In the internment camps, mortality rates will have reached values between three and 13 percent. [3] The occupation operations of vast territories in Southeast Asia carried out by Japanese military forces during World War II reached their maximum geographical limit further south with the invasion of Portuguese Timor on February 20, 1942. Officially ordered in response to the presence of Australian and Dutch military forces in neutral Portuguese territory, the Japanese military occupation lasted for about three years, until September 1945, during which harsh living conditions were imposed on the populations. Throughout this period, Japanese forces stationed in Timor they maintained a conduct of deliberate submission of their prisoners and civilian detainees to violence, torture and public humiliation. Without resorting to direct confrontation, they skilfully led and armed violent bands of natives who sowed terror among the hundreds of Europeans and Timorese who had sought the deemed safe refuge of the mountains, leading them to ask the invader to establish zones concentration under its protection. Over time, these places of voluntary concentration ended up being transformed, despite the lack of walls or fences, into veritable concentration camps where hunger raged and violence prevailed. This text has as main objective to describe, with the detail allowed by the available sources, the main events that led to the creation in Timor of zones of concentration of Europeans; its geographical dispersion and evolution over the three years of Japanese domination; the living conditions and methods used by the invading forces to subjugate the European and Timorese concentrates. Timor in the Second World War: the “invasion” by Australians and Dutch [4] In the midst of World War II, in December 1941, and despite protests from the Portuguese authorities, an allied contingent made up of Australian and Dutch forces landed in Timor on the pretext of strengthening the defense capacity of the Portuguese colony. The Australian Government, following talks with the Dutch Government, had undertaken to provide military aid if the territory of Dutch Timor was invaded by Japanese forces. This support would become effective on December 12, 1941 when a detachment of the Australian Army, with the designation «Sparrow Force» [5] and with a force of around 1400 men, landed in Kupang, in the Dutch part of the island of Timor. Until then, Portugal had refused the military support for the defense of the territory of Timor insistently offered by the Dutch and Australians, confident that it was in its neutrality. [6] The military activity of the Portuguese colony was then far from being effective since most of the European graduates sent to the territory was “deviated” to functions in the local administration due to the lack of capable civil servants. By the time of the Second World War, the tiny garrison existing there was reduced to a company of indigenous infantry (Companhia de Caçadores de Timor) and a platoon of cavalry, also indigenous (da Fronteira), a military device that, officially established at the end of the 1930s, could be considered sufficient for maintaining internal order, but totally insufficient and inadequate to sustain any external attack. The Companhia de Caçadores de Timor was headquartered in Taibessi, three kilometers from Dili; in Maubisse there was a school for recruits and in Oecussi a detachment of that company was stationed. The Border Police Cavalry Platoon had its forces distributed along the border with Dutch Timor and its command was based in Bobonaro. In addition to this 1st-line military device, a significant number of 2nd-line indigenous voluntary forces, called moradores, were also organized in the various Regulados [7] of the territory, which in the past had helped to put down internal insurrections. The colony's military garrison had a total strength of three officers; seven sergeants and about 30 European, mestizo and indigenous corporals; four European and mestizo soldiers; and about 300 indigenous soldiers. [8] Since June 1941, 12 independent companies (commandos) were being secretly prepared by the Australian Army to act behind enemy lines. Confronted with the rapid Japanese expansion in the Pacific, the Australian military leaders decided to take advantage of these units to defend the cordon of islands located to the north and northeast of Australia in order to function as outposts where they hoped to sustain a first onslaught of the enemy. In this context, an independent Australian company would initially land in Dutch Timor, but would end up, together with Dutch military forces, being deployed to Portuguese Timor, where it would later be reinforced by another independent Australian company. On December 17, 1941, around one o'clock in the afternoon, contrary to the wishes of the Portuguese authorities, and under the pretext of the imminent Japanese invasion of the Portuguese colony, the Australian and Dutch forces disembarked in the vicinity of Dili. [9] The Portuguese governor, Manuel Ferreira de Carvalho, upon learning of the entry in the territory of those forces, made it known that it had not requested any external help for the defense of the territory and, therefore, could not agree with the ongoing action, considering it a hostile occupation action. Once the Allied invasion was completed, considered by Portugal as unjustified, since the assumption of the invasion of the territory by Japanese forces had not been verified, the Portuguese authorities protested to the Dutch and Australian governments and the governor of the colony declared himself prisoner of the invading forces. Five days later, a note was delivered to the British ambassador urging the Australian and Dutch troops to leave the territory as soon as the Portuguese military contingent arrived in Timor, which, meanwhile, was being prepared in Mozambique and which would have a number manpower equivalent to that of the occupying Allied forces. On January 26, 1942, after negotiations with the British and Japanese, an expeditionary contingent destined for Timor finally left Lourenço Marques (Mozambique). The force consisted of a chasseur company, an engineering company and an artillery battery. [10] On February 2, 1942, the first Japanese attacks on Kupang, in the Dutch part of the island, were reported. The war was getting closer and closer to Portuguese Timor. On February 17, the Portuguese ship João Belo was off Dili and had already established radio contact with land, where all the preparations for receiving the Portuguese expeditionary force had been completed, when the unforeseen event occurred. The Japanese authorities, who had previously agreed with the sending of the Portuguese military force, informed that they would not allow its disembarkation and, given this development, the Portuguese force withdrew to Colombo, in Sri Lanka, and later, to India, where it was until February 1945 and from where he would finally return to Mozambique. The invasion and occupation by the Japanese imperial forces At the same time that the Portuguese authorities sought to assemble in Mozambique the personnel necessary to replace the Dutch and Australian forces stationed in Timor, the Portuguese Government he also sought by all means to maintain a constructive diplomatic dialogue with the Japanese authorities, which would allow controlling any Japanese retaliation arising from the presence of those forces on Timorese soil. On 19 February, the secretary general of the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Teixeira de Sampaio, received in private audience the Minister of Japan in Lisbon, who was the bearer of an urgent official message. The latter, after the usual greetings, informed the Portuguese ruler that, for reasons of self-defence, the Japanese Imperial Government had decided to expel the Dutch and Australian forces from the Portuguese colony of Timor. He further requested that the Japanese occupation of Timor be considered neither an act of war against Portugal nor a form of attack on Portuguese neutrality. Japanese forces would withdraw as soon as the need for self-defence ceased to exist. Three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the occupation of Southeast Asia carried out by Japan reached its southernmost limit with the invasion of Portuguese Timor, officially in response to the presence of Australian and Dutch military forces in a «neutral country». On the night of February 20, 1942, Japanese forces landed in various parts of the Portuguese colony, beginning an occupation that would last until the end of WWII. Gradually, Japanese military forces occupied a significant part of the territory and came to dominate almost all of its coastline. From May 31, 1942, Governor Ferreira de Carvalho and the few administrative employees who had remained in Dili saw their movements restricted to their official residence and contacts with the metropolis were no longer possible. Dili was then practically deserted. Most of its inhabitants abandoned the city and sought refuge in the interior of the territory. The reduced Portuguese military forces were, however, instructed by the governor not to offer resistance and were moved to Aileu, where the bulk of the civilian population was taking refuge. Here, one of the biggest massacres perpetrated by Japanese forces would take place with the collaboration of the infamous «black columns» [11], organized by the Japanese using inhabitants of the locality of Atamboea (Dutch Timor) who, initially, had been enlisted as porters. Timorese, Australians and Dutch were thus forced to seek refuge in the mountains, where they carried out resistance and guerrilla actions against the invader, greatly favoured by the difficult characteristics of the relief and by the unconditional support of the local populations. Many Timorese were eventually executed by the occupying forces, accused of collaborating with resistance elements. The most famous case of Timorese resistance to the invader is that of D. Aleixo Corte Real, ruler [12] of Ainaro, and his subjects, who were surrounded by Japanese forces and by elements of the «black columns» in the mountains of Suro-Lau, where they resisted for a few weeks. The lack of food and ammunition led D. Aleixo to surrender along with his warriors. Imprisoned and summarily judged, they ended up dying at the hands of the Japanese invaders. Throughout the first five months of occupation, guerrilla actions managed to inflict serious damage on the occupying military forces; however, starting in August 1942, Japanese forces launched a counteroffensive that led to the interruption of most cooperation circuits between local populations and resistance forces. Unable to respond militarily, Portugal tried at all costs to negotiate with the Japanese authorities adequate conditions of coexistence, but after exhausting all possibilities of understanding, there was no other solution than to request the support of its international allies with towards the liberation of Timor. Impossible To Resist The definitive breaking point with regard to the security of the populations of the colony of Timor took place at dawn on 1 October 1942. That dawn, and the day that followed, the village of Aileu, the town in the mountains where a large part of the European and native inhabitants loyal to the Portuguese authorities had taken refuge, was swept by a wave of destruction and death, the most serious hitherto experienced since the invasion. With the cover and support, less and less disguised, of Japanese forces, a large «black column» coming from Dili assaulted the military barracks there. [13] The military unit that was stationed there (Companhia de Caçadores de Timor) was a one of the few still in operation in the whole territory, and it had gathered the bulk of the troops left over from the Portuguese armed force that had played an active role in the actions carried out to quell the indigenous revolts that since the Japanese invasion had arisen in various parts of the colony. [14] This assault on Aileu had, as the governor of Timor Manuel Abreu de Carvalho would later write in his report on the events of those days, a single objective «previously and thoroughly prepared» and that involved dismantling the residual capacity of Portuguese military response still existing in the territory. [15] In addition to the commander of the military unit, Captain Ferreira da Costa, several European and indigenous soldiers were killed, as well as some European civilians who had taken refuge in that officer's house. In possession of the reports of events made by the few survivors who ended up managing to reach Dili, the Portuguese governor found that he no longer had the capacity, with the means at his disposal, to face an «extermination program» [16] that would certainly have continuity until the complete subjugation of the Timorese, Europeans and indigenous peoples. Especially targeted in the violent actions perpetrated by the «black columns», the non-indigenous population that was dispersed throughout the territory had exhausted all its capacity for resistance and was at serious risk of annihilation, therefore requiring rapid action by the governor. Having assessed the general security conditions, Governor Abreu de Carvalho concluded that the only means of effectively protecting this population would be to submit to the authorities in Lisbon and the Japanese consul in Timor a request for the Portuguese population to leave the territory. In Lisbon, the request was not favourably received as it was considered an action contrary to the maintenance of Portuguese sovereignty over the territory. The Japanese consul, recognizing the need to find an urgent solution to the situation, proposed, as an alternative, placing the Portuguese population under the protection of Japanese military forces. Reluctant to accept the protection proposed by the Japanese, only after two tense negotiation sessions with the Japanese military command, during which he tried to obtain the best guarantees of protection and security, as well as the clear definition of the concentration zones, he agreed Governor Ferreira de Carvalho to sign an official request to protect the lives of the Portuguese. As concentration zones, in addition to Dili, the locations of Liquiçá and Maubara were defined, an area that would come to be dubbed the «butcher shop of the Portuguese». The Concentration In Liquiça And Maubara On November 25, 1942, the Portuguese governor ordered the beginning of the concentration of the Portuguese who were dispersed throughout the territory, starting with the residents of the Baucau region, located 122 kilometers east of the capital, Dili and where, by order of the governor, the alternative headquarters of the government of the colony had been established in July of that year. [18] With clear and well-defined instructions for those responsible for the various administrative districts, the evacuation plan from the interior of the territory to Liquiçá and Maubara established that all movements had to be carried out with special care so as not to affect either the lives of the native inhabitants or the «prestige» that the European Portuguese had among them. The administrative authorities should be the last to leave, ensuring the choice of an indigenous chief who, due to his prestige and trust, would be responsible for looking out for the interests of the populations and for guarding the assets of the Portuguese State that could not be moved. From the posts [19] and from the various administrative districts, archives and all equipment that could be of some future use should be protected and evacuated. With regard to the foodstuffs intended to feed the displaced people, the instructions were also clear: buy locally everything possible (corn, wheat, rice, beans, oil, potatoes, fats, etc.). Likewise, fuels such as petroleum, gasoline and alcohol had to be purchased. [20] In the weeks that followed, without the attacks by elements of the «black columns» taking place in various parts of the territory, and despite the hardening of the Japanese forces' action in relation to the European Portuguese, the governor continued with the actions foreseen in the plan of evacuation and concentration outlined, and determined the appointment of two new «heads of post», two sergeants, for the localities of Liquiçá and Maubara, where the concentration of inhabitants from Baucau and other points would take place from inside the territory. There would then be three concentration nuclei: Dili, where about three dozen Portuguese, including the governor, his family and the administrator of the municipality of Dili, were kept by imposition of the occupying forces since the day of the invasion; Liquiçá and Maubara, which would receive around 400 people and where the Treasury Services (Finance) and the Services of the Military Division would be installed. In Dili, and despite the reduced number of employees there, the Governor's Office Division, the Civil Administration Services continued to operate; the Health Department, the Municipal Services and Public Works, the Treasury Fund (in charge of the Nacional Ultramarino bank) and the hospital. [22] Medical assistance to the population was provided by three Portuguese doctors (in Dili; one in Liquiçá and one in Maubara) and by four European nurses and 14 indigenous nurses distributed across the three locations and Oecussi. Religious assistance in the three concentration centres was provided by four missionaries. Later, in view of the difficulties experienced in obtaining food for the concentrates, the Transport Services (land and sea) and the Supply Service were created, whose mission was to acquire, by whatever means possible, the foodstuffs necessary to feed the concentrated Portuguese, subsequently promoting their equitable distribution or their free sale in case of excess stocks. [23] Fig. 1 — Areas of concentration and localities of origin of the concentrated population [20] The public mail and telegraph services did not work, as did the justice services. There were national flags hoisted daily at the governor's residence, hospital building in Dili, Liquiçá, Maubara, Oecussi and at border posts, in affirmation of Portuguese sovereignty over the territory. As Ferreira de Carvalho would later mention: «The concern at the end of 1942 was to organise things, especially with regard to supplies, in order to make the existence of the Portuguese in the area as less precarious as possible.» [24] At the beginning of 1943, around 150 European Portuguese, public and civil servants, and their families remained in Timor. The rest had, with the help of Australian naval forces, left the territory. Gradually, these Portuguese arrived in the concentration areas of Liquiçá and Maubara, where they settled, the first to arrive, in the available housing, the rest, as they could. There, the action of the “black columns” continued to be felt not only in the vicinity of those areas, but also, and with some frequency, within them. In the neighbourhood, there were also some Australian forces who, with the help of faithful natives, were looking for the best opportunity to attack the small Japanese military detachment stationed there. The difficulties inside the concentration zones grew over time. Alongside the progressive scarcity of foodstuffs, the difficulties related to obtaining medicines also grew. Medicines that the governor proposed several times to buy from the Japanese. However, of the approximately 70 products requested from the Japanese consul, only 17 would be supplied and even then, 11 months later. [25] About 700 people lived in the areas of Liquiçá and Maubara in mid-1943, including European and indigenous Portuguese. They lived in a state of extreme physical and psychological vulnerability, insecurity and fear, which created an environment of general demoralisation, impotence and tension among the inmates. In a short time, the occurrence of petty theft became regular among the concentrated; slaps and attacks from the camp guards, a constant; prison, arbitrary; the beatings and torture, a certainty. With difficulty, and within the possibilities of the moment, he tried to normalize the life of the concentrates and provide for their most urgent needs. Within the concentration zones, and despite the restrictions imposed by the Japanese, European and Timorese Portuguese began to develop a certain autonomy and routine in community life. In view of the high number of children in Liquiçá and Maubara, in mid-July 1943, a school was opened in each of the two locations, where teachers continued to ensure the elementary education of children. Without any school material, 138 students started to attend the school, a number that grew in the following two years. At the end of 1943, and in the following two years, the «normal» exams for the 3rd and 4th grades were held. [26] In September of the same year, a nursing course would also begin in Dili and Liquiçá directed by two Portuguese doctors (Dr. Santos Carvalho [Díli] and Dr. Rodrigues [Liquiçá]), frequented by Europeans and indigenous people who have completed the primary education exam. Students on this course were only able to complete the first year of training as there were no resources to allow them to teach the practical classes planned for the 2nd year. [27] At the end of July 1943, the command of the Japanese military forces ordered the collection of all radio equipment existing in Dili, as well as all the equipment used for its installation and operation. Thus, until the end of the war, any possibility of official communication with the outside of the colony was prohibited. The Japanese military police, Kempetai, insistently inspected all places where such equipment could be hidden. His deepest fear was subversion, sabotage and revolts fomented by information that secretly circulated through the most diverse means. [28] Radio equipment constituted an effective and fast means for the dissemination of information and instructions over short and long distances and they were therefore considered a central element in the planning and execution of any conspiracy. Whenever they suspected the existence of radio equipment operating for subversive purposes, elements of the Japanese military police did not hesitate to interrogate, torture and even execute the individuals believed to be in possession of that type of equipment. With all the financial reserves of the government of the colony exhausted, and with no possibility of funds being sent from Lisbon to meet the needs, the governor developed the necessary contacts with the Japanese authorities in order to obtain a loan of 400 thousand yen or gulden from the Japanese Army. The terms of the loan having been established between the parties, it was granted and signed on November 8, 1943, and on the 20th of the same month the legislative diploma was published in which the Colony Government authorized the circulation of the new currency in equal value with the pataca. In October 1944, a new loan was taken out from the Japanese authorities in the amount of 200,000 gulden and in March 1945, another 400,000. Only with recourse to these three loans was it possible to continue to acquire the goods necessary for the survival of the concentrates. However, the difficulties in obtaining foodstuffs and the high prices charged mainly by the Japanese, but also by the indigenous people who had them, made their purchase unaffordable for most Portuguese with a lot of family. In Maubara, the concentrated Portuguese still managed to cultivate some land with reasonable results, although very insufficient to supply the needs. In Liquiçá, the poor quality of the soil and the scarcity of water doomed all attempts at cultivation to failure. Between 9 and 16 March 1944, with monitoring and strict control of movements by the Japanese authorities, Captain Silva Costa, special envoy of the Lisbon authorities, traveled to Timor from Macao in order to investigate the living conditions of the Portuguese in that colony. Having reserved two days to visit the concentration zones of Liquiçá and Maubara, in the report that he later presented to the Minister of Colonies Silva e Costa very telegraphically reports what he witnessed there, limiting himself to mentioning that «[...] saw no one with the appearance of hunger or serious illness, regular physical appearance” and “there are old people between 60 and 70 years old [...]”. Concerned with obtaining answers to the questions raised in the extensive inquiry that had been sent to him by Lisbon, questions that largely focused on the governor's actions since the beginning of the occupation, and despite, as he mentions in his report, having held a conference ‐ either with the governor or with concentrated Portuguese, he flagrantly failed to correctly assess his living conditions. [29] From April 1944, the health status of the concentrates in Liquiçá began to deteriorate significantly, to the point of being classified as very bad by the Portuguese health delegate during the months of June and July. Malaria; scabies; tuberculosis; serious dental diseases caused by the lack of foods rich in vitamin A, C and D, but also by the lack of toothbrushes and toothpaste for oral hygiene; intestinal poisoning resulting from the ingestion of plant species unfit for human consumption; beriberi; difficult-to-heal ulcers and general weakening of the population contributed to that classification. [30] As if the existing difficulties were not enough, the areas of Liquiçá and Maubara began, at the beginning of the year, to be periodically machine-gunned, presumably by Allied planes that were trying to reach the small Japanese military detachment stationed near those locations. As a result of these actions, several adults and children, European and indigenous Portuguese, were seriously injured, pierced by projectiles. [31] The cycle of degradation would continue in 1945. In the month of May, the state of health of the Portuguese in Liquiçá was so serious that the Japanese themselves sent a doctor to observe them. Assisted by a nurse, he examined and treated around 80 patients; they even made dressings for wounds and ulcers. «The treatments carried out consisted of injections of vitamin b1, and distribution of roles of this vitamin in solid concentrate, cod liver oil and aspirin tablets.» [32] When, in September 1945, the occupation of Timor was declared to have ended due to the surrender of Japan, the general state of health of the Portuguese who still remained in the concentration zones was one of extreme weakness due to lack of food. They were «skeletal, almost unrecognizable at first sight», they were «[...] walking skeletons, true ghosts of themselves [...]». Later, in 1972, José dos Santos Carvalho, a doctor and health delegate, wrote about the evaluation he had carried out at the end of the war of the health status of the concentrated Portuguese: In almost all of them, I observed the following symptoms: extreme emaciation, transparent skin glued to the bones, extremely pale complexion, sunken and dull eyes, uncertain gait, stooped torso, lack of physical vigour, depression of the will, erased memory, atrophied muscles, caries or falls. teeth, malleolar [lower limbs] or facial oedema, heart palpitations at the slightest exertion. How to explain them? By hunger. Nutrition deficiencies [...] led us to organic misery and would end up giving them natural death [...]. About the number of deaths that occurred during the period of concentration, the cited report does not give any indication; however, José Duarte Santa, the Liquiçá post chief, would later report the deaths of 14 of the 521 Portuguese who had been interned in the Maubara and Liquiçá concentration zones (287 males and 234 females). In the remaining Timorese territory, 164 Portuguese and around two thousand indigenous people died. [34] Prisoners Of War In addition to the Portuguese concentrated in the conditions just described, in Timor, there were also European and Timorese Portuguese, military and civilian, imprisoned and tortured for reasons directly related to the war. On July 10, 1944, a Portuguese soldier, Lieutenant António Oliveira Liberato, and three prominent Portuguese civil servants [35], were, after being detained and interrogated by the Japanese military police, the feared Kempetai, transferred by sea to a place of captivity located on the island of Alor, called Kalabai, where they were detained in a rudimentary house, surrounded by barbed wire, guarded by armed indigenous people commanded by a Japanese soldier. The displacement of thousands of prisoners of war by sea was put into practice by the Japanese in the first months of the war. Due to the need for manpower, ships full of prisoners circulated daily between Java, Sumatra, Borneo, Timor. [36] In an intense war zone, these prisoners were transported, in conditions similar to those of transporting animals, in old freighters without any external identification, which is why they were frequently torpedoed, bombed and sunk by Allied aviation. Other POWs, subjected to endless long-distance voyages on overcrowded and slow-moving ships, eventually died of asphyxiation, starvation, or disease. [37] Accused of collaborating with Australian and Dutch forces, Lieutenant Liberato, like other inhabitants, had been detained two months before, and during his captivity in Dili he was subjected to tight interrogation which included torture sessions, «tortures of unspeakable inhumanity». [38] According to various reports, the prisoners were tied by the wrists with a rope, then hung from the prison bars and hoisted so that their feet did not touch the ground. Endless sessions of interrogations and beatings followed, only interrupted for brief periods to rotate the interrogator or else, following some program of psychological action on the prisoner who, after being beaten, sat him down at the table, talk friendly to him, give him some food and cigarettes, and then hang him on the bars again. The so-called «water torture» was also applied to Timorese prisoners, which consisted of laying the prisoner «[...] on his back, on a platform, tied hand and foot, with a funnel inserted into his mouth, by force, between teeth, filled the patient's stomach with water. After the first dose was expelled through the mouth, through the nostrils and through the ears, another was repeated [...].” [39] They would remain in Kalabai until January 1945, isolated, poorly fed [40] and frequently bombed by Allied planes, whose actions would result in the injury of one of the Portuguese. Similar to what happened in Maubara and Liquiçá, the health status of these prisoners gradually deteriorated and led to the appearance of beriberi among the Portuguese. «[...] everything had already disappeared, even the wedding rings, and they had nothing with which to find anything to eat other than what was provided for them and the organism refused.» [41] On February 23, 1945, he died the first Portuguese, engineer Canto Resende. Observed by a doctor on March 20, the remaining three Portuguese were diagnosed with beriberi and malaria without, however, being provided with any type of treatment. On the 25th of that month, another Portuguese (BNU manager João Duarte) died, swollen and with serious mobility difficulties. Barefoot for not being able to put on shoes, on March 28, 1945, they started a march that would last two days and during which they would cover about 12 kilometers, ten on the first day, two on the second in very poor health and unable to walk, Lieutenant Liberato was transported on a stretcher supported by four men. They stayed in the village of Railaco until April 18 of that year and from there they continued on to Kelass, subject to the same difficulties in terms of accommodation and food. There they remained for five days, Lieutenant Liberato, very weak due to malaria and beriberi, without any medical assistance and with only six quinine pills, grudgingly supplied by the Japanese. On the 26th of June, they begin a new trek to Makoada. They would leave the island of Alor on the 23rd of August, arriving in Dili on the 28th of the same month. Only the following day, and after intervention by the governor with the Japanese consul, would they be definitively released. [42] Fig. 2 — Itinerary of Portuguese prisoners [43] On September 5, 1945, the Japanese military commander officially informed the governor of the Portuguese colony of the cessation of hostilities at the request of Japan and the return of the territory of the colony of Timor “to the fullness of Portuguese administration”. [44] Four days later, the command of the Japanese military forces ordered the transfer of the Portuguese who remained in Maubara (about 200) to Liquiçá, which would take place on the 14th and 15th of that month. In a context of overpopulation concentrated in Liquiçá, the food problem worsened significantly, reaching in October the lowest level ever: an average of 471 grams of foodstuffs, around 1050 calories a day. The reoccupation of the Portuguese colony began at the Liquiçá and Maubara posts, and only ended on November 21, 1945. It was carried out without weapons, by a group of 163 European Portuguese, 19 indigenous administration officials and 14 salaried workers. The Australian military authorities, who traveled to Dili on September 23 to deal with the governor about the surrender and withdrawal of Japanese forces from Timor, immediately proposed carrying out an inquiry into war crimes committed by the Japanese during the occupation of the territory. Alleging a lack of instructions on the subject, the governor rejected the proposal to create a joint commission of inquiry, noting that «with regard to the Portuguese and the indigenous populations of the colony, the Portuguese authorities would carry out the inquiry». [45] In a telegram dated September 26, the Minister for Colonies instructed Governor Ferreira de Carvalho to provide all the necessary support to an Australian mission that would travel to Dili to carry out the aforementioned inquiry, passports having already been issued on that date. and seen by some senior Australian entities in charge of carrying out the said investigations. [46] The governor would later mention in the report he wrote on the events in Timor that, until his departure from the colony on December 8, 1945, he had not No Australian authority had appeared to carry out the inquiry and neither had the central government given any further statement on the matter or ordered any action. We know today that on June 21, 1946, two members of the Australian War Crimes Commission arrived in Dili to investigate war crimes committed by the Japanese in Timor. The contacts established with the local Portuguese authorities resulted in the creation of a joint investigation commission composed of Australian elements, a member of the Portuguese administration and an officer of the Dutch Army. In the reports that these elements wrote a posteriori, they clearly expressed not only the reduced cooperation received from the Portuguese authorities, but also their obstructive action to the investigations carried out. [47] In 1946 and 1947, the new governor of Timor, Óscar Ruas, dedicated special attention to the punishment of Timorese who had collaborated with the Japanese forces and had committed violent war crimes in their service. More than a thousand individuals were accused throughout the Timorese territory, who were arrested and later sent to the island of Ataúro where, once judged, many ended up being convicted. Final Considerations The experiences lived in captivity in the various Asian territories occupied by the Japanese during WWII varied enormously, despite the existence of certain standards of action by the Japanese imperial military forces with regard to the implementation and control of prisoner camps of war or the internment of civilians. In the four years that the conflict lasted, and especially during the operations of the Pacific War, there was no uniform “Japanese model” for establishing that type of camp or for treating prisoners of war or civilian internees. Differences, many of them significant, are noticeable from field to field and are due not only to the combatant/non-combatant status of the imprisoned individuals and their nationality, but also to the geography of the events and, above all, to the nature of the events, camp commanders and military garrisons responsible for their security. In the Japanese military, the appointment of an officer to command a prison camp was not looked upon favourably. Thus, and although there were conscientious ones, the possibility of prisoners and internees being subject to the free will of a mediocre, incompetent or sadistic field commander was very high. In the Portuguese colony of Timor, no concentration camp was built for prisoners of war following the invasion, and subsequent occupation, of that territory by the Japanese imperial forces in February 1942. Yes, there was, at the request of the local Portuguese authorities, and for security reasons, the establishment of concentration zones where mainly European Portuguese and some Timorese ended up being subject to the same type of hardship and humiliation characteristic of aspects of the Japanese military's treatment of prisoners of war in most of the territories they occupied. But there were also prisoners of war in the true sense of the words. Prisoners who, initially detained in ordinary prison facilities for minor matters, ended up being subjected to the most violent acts of torture, forced expatriation and a life in miserable conditions. It was on these largely forgotten aspects of the Japanese invasion of Timor that we sought to shed light from the scarce sources available, mostly memorialistic. Unexplored, despite some established international contacts, are the possible archival sources in the Japanese language, due to the fact that they were not obtained in a timely manner, but also, and above all, due to the language barrier that is expected to be broken in the future by some scholar in favour of a more plural reading and a more complete understanding of the matter in question. The Japanese occupation of Timor brought starvation and violent death to an already impoverished local community, with a violence that led to the destruction of the most basic social practices and the collapse of Portuguese administration in the colony. It should be recalled that the Japanese forces invaded Timor on the pretext of self-defence arising from the presence of Australian and Dutch forces on that island. However, using and manipulating the «black columns» skilfully, over time they created a permanent state of terror. A state to which they were deliberately giving contours of fratricidal war intended to conceal a real open war and to create conditions for the Japanese authorities to disclaim responsibility for the violent acts that, under cover of that, were practiced by their military. The governor of Timor, Manuel de Abreu Ferreira de Carvalho, wrote about this period: It was a period without history, or rather, in which history is reduced to a few words: it was necessary for the Japanese not to defeat us in this relentless struggle in order to annihilate us physically and morally; whatever happened, they would not defeat us because we had to resist. [48] Notes [1] Gavan Daws, Prisoners of the Japanese: POWs of World War II in the Pacific (New York: Harper Perennial, 1994), 17 et seqs. [2] Idem, ibidem, 100. [3] Kevin Blackburn and Karl Hack (ed.), Forgotten Captives in Japanese Occupied Asia (London: Routledge, 2008), 2‐5. [4] For the excellent context it offers of the events that took place in Timor during WWII, see António Monteiro Cardoso, Timor na 2.a Guerra Mundial - o diário do Tenente Pires (Lisboa: Centro de Estudos de História Contemporânea, ISCTE, 2007). [5] On the actions of this Australian military force, see Bernard Callinan, Independent Company: the Australian Army in Portuguese Timor 1941-43 (London: William Heinemann, 1953). [6] See, among other authors and works, Carlos Teixeira da Motta, O Caso de Timor na II Guerra Mundial. Documentos britânicos (Lisboa: Instituto Diplomático, 1997). [7] Reinos. [8] Arménio Ramires de Oliveira, História do Exército português, 1910‐1945, volume III (Lisboa: Estado‐maior do Exército, 1994), 497 et seqs. [9] For a description of the first actions of these military forces after the disembarkation see, among others, the one carried out in Carlos Cal Brandão, Funo: Guerra em Timor (Porto: Edições A.O.U., 1946), 43‐48. [10] Carlos da Rocha Vieira, Timor - Ocupação Japonesa Durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial (Lisboa: SHIP, 1994), 38. [11] Atamboea natives armed with spears and machetes and framed by elements of the Japanese secret police. Vieira, Timor - Ocupação Japonesa Durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial, 76. [12] King; tribal chief. [13] José Duarte Santa, Australianos e Japoneses em Timor na II Guerra Mundial, 1941‐1945 (Lisboa: Notícias, 1997), 60. See also Brandão, Funo: Guerra em Timor, 78‐83. [14] On the indigenous revolts see Cardoso, Timor na 2.a Guerra Mundial, 62‐66. [15] Manuel de Abreu Ferreira de Carvalho, Relatório dos Acontecimentos de Timor (1942‐45) (Lisboa: Cosmos, 2003), 397. [16] Idem, ibidem, 397‐399. [17] António de Oliveira Liberato, o Caso de Timor (Lisboa: Portugália, 1945), 233. [18] On the Japanese military occupation of Timor during World War II, and in particular with regard to the living conditions of the European Portuguese in the Liquiçá concentration zone, see Rosas de Ermera, by Luís Filipe Rocha (2016; Fado Filmes). The documentary, based on the autobiographical work of João Afonso, o Último dos Colonos - Entre um e outro mar (Lisboa: Sextante, 2015), describes the separation of the Afonso dos Santos family in 1939 in Mozambique, the trip to Coimbra of the two brothers, João and José (Zeca Afonso) and the departure of the parents and the youngest daughter, Maria das Dores, to Timor. In the second part of the documentary, Maria describes in detail various aspects of her daily life during the occupation of the territory by the Japanese military forces and, in particular, her internment for three years in the Liquiçá concentration zone. [19] Administrative post. [20] Ferreira de Carvalho, Relatório dos Acontecimentos de Timor, 431. [21] Map adapted from António de Oliveira Liberato, Os Japoneses Estiveram em Timor (Lisboa: Empresa Nacional de Publicidade, 1951). [22] Ferreira de Carvalho, Relatório dos Acontecimentos de Timor, 472. [23] On the difficulties experienced in obtaining food, see Brandão, Funo: Guerra em Timor, 178‐179. [24] Ferreira de Carvalho, Relatório dos Acontecimentos de Timor, 467. [25] Idem, ibidem, 487. [26] In the second part of the documentary (min. 37) Rosas de Ermera, Maria das Dores fala do seu exame da 4.a Classe realizado em Liquiça. (disponível em http://media.rtp.pt/extra/estreias/rosas‐de‐ermera/). [27] Ferreira de Carvalho, Relatório dos Acontecimentos de Timor, 498. [28] Gavan Daws, Prisoners of the Japanese, 131. [29] See existing documentation at the Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo under the reference PT/TT/AOS/A/8/8/00003. [30] José dos Santos Carvalho, Vida e Morte em Timor Durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial (Lisboa: LivrePortugal, 1972), 176‐178. [31] Idem, ibidem, 166. [32] Idem, ibidem,171. [33] Idem, ibidem, 176-177. [34] Santa, Australianos e Japoneses em Timor na II Guerra Mundial, 164‐165. [35] Artur do Canto Resende (geographer engineer), João Jorge Duarte (manager of Banco Nacional Ultramarino) and José Duarte Santa (administrative aspirant, head of post in Liquiçá). Ferreira de Carvalho, Relatório dos Acontecimentos de Timor, 598 et seqs. [36] See Janet Gunter, “The restless dead and the stripped empire: World War II and its aftermath in Timor‐Leste”, in Timor‐Leste: Colonialismo, Descolonização, Lusotopie, ed. Rui Feijó, 115‐137 (Porto: Afrontamento, 2016). [37] Gavan Daws, Prisoners of the Japanese, 283‐287. [38] «[...] according to good Japanese habits, accompanied by several aggressions, on the 11th [April 1944] this officer was hung by his wrists from the bars of the prison window, and thus interrogated, removing him from under his feet a bench he relied on whenever his answers didn't satisfy them. This ordeal, accompanied by the torture of thirst, [...] lasted until Lieutenant Liberato, already exhausted and unable to bear it any longer, lost consciousness. [...] In the interrogations of April 24 and 25, they resorted to moral torture, telling him on some occasions that they had arrested his wife [...] and on others that Lisbon had been bombed and destroyed by German aviation.». Ferreira de Carvalho, Relatório dos Acontecimentos de Timor, 573‐579. [39] Liberato, Os Japoneses Estiveram em Timor, 173. On other torture methods, see Cardoso, Timor na 2.a Guerra Mundial, 117. [40] «[...] a few spoonfuls of cooked rice, sometimes accompanied by a decilitre of broth, at each meal Ferreira de Carvalho, Relatório dos Acontecimentos de Timor, 602. [41] Liberato, Os Japoneses Estiveram em Timor. [42] For a more detailed description of the facts, see Santa, Australianos e Japoneses em Timor na II Guerra Mundial, 183‐280. [43] Map adapted from Liberato, Os Japoneses Estiveram em Timor. [44] Ferreira de Carvalho, Relatório dos Acontecimentos de Timor, 662. [45] Cardoso, Timor na 2.a Guerra Mundial, 116. [46] Ferreira de Carvalho, Relatório dos Acontecimentos de Timor, 702‐710. [47] On the practical results relating to the punishment of perpetrators of war crimes identified in investigations carried out by the Australian authorities in Timor, see Cardoso, Timor na 2.a Guerra Mundial, 116 ‐118. See also William Bradley Horton, «Through the eyes of Australians: the Timor area in the early postwar period», Journal of Asia Pacific Studies (Waseda University), N.o 12 (2009): 251‐277. [48] Ferreira de Carvalho, Relatório dos Acontecimentos de Timor, 475.

-